“Revolutionary literature requires revolutionary politics”: An Interview with Meena Kandasamy

Acclaimed author Meena Kandasamy discusses the uncompromising and unapologetic resolve in her writing, confronting violence with art, and why activism is a form of love.

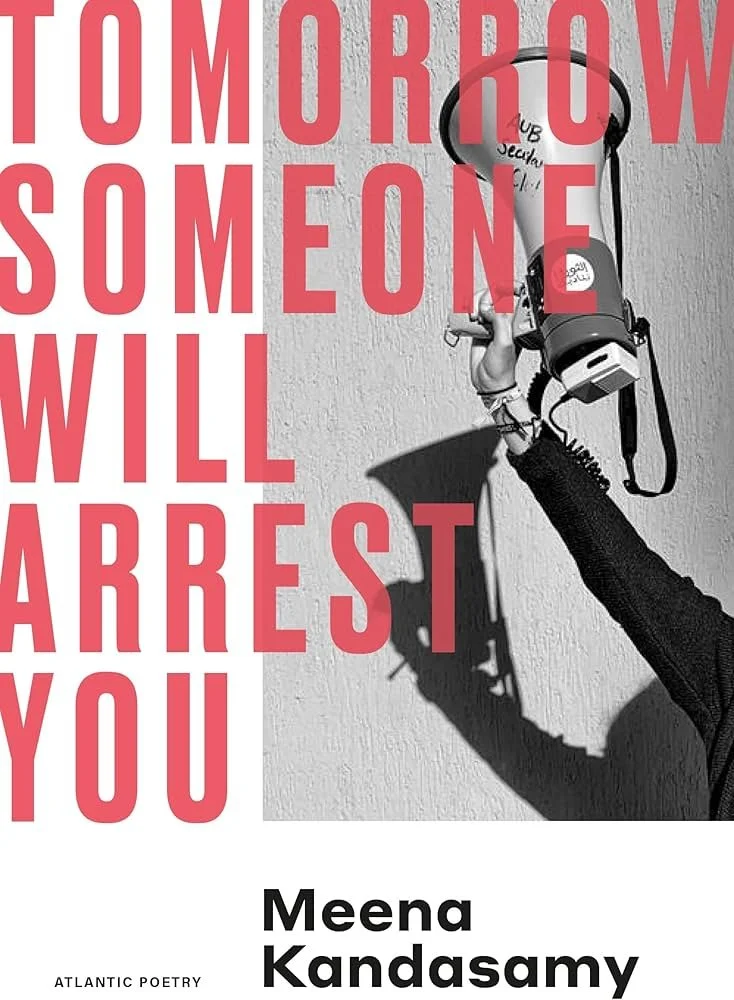

In the dramatis personae of her poetry collection, Tomorrow Someone Will Arrest You (Juggernaut, 2024), Meena Kandasamy writes, “Her country is that land where she is instantaneously considered a troublemaker.”

There’s a hint of pride Kandasamy takes in being called a ‘troublemaker,’ reflecting on her identity in relation to her country, whose establishment feels shamed by anyone saying the unsayable, but that’s what Kandasamy has championed throughout: being a storyteller, and owning her story.

She takes “authorship … very seriously”, as the narrator of her Women’s Prize for Fiction-shortlisted book When I Hit You Or, a Portrait of the Writer as a Young Wife (Juggernaut, 2017) submits. Kandasamy isn’t interested in becoming “a footnote” in anyone else’s story. Her principles remain the book’s narrator: “Don’t let people remove you from your own story. Be ruthless, even if it is your own mother.” Or your motherland, if one must add to it.

In an email interview with The Chakkar, the poet discusses the uncompromising and unapologetic resolve in her writing, confronting violence with art, and why activism is a form of love. Edited excerpts:

The Chakkar: In your works, there’s an allusion that activism (literary and otherwise) is in itself a form of love. In Tomorrow Someone will Arrest you: “words as weapon” are noted as an “offering made to a lover” while describing ‘The Poet.’ This signals that the scribe doesn’t want her words misconstrued, hyper-focusing on the specificity she demands. Then, in The Orders Were to Rape You: Tigresses in the Tamil Eelam Struggle (Navayana, 2021), you note that one never considers an “activist as author.” Could you help describe work as an act of love, blurring the ‘personal’ and the ‘political’ and inviting intimacy to take centre-stage?

“I choose to meditate on violence because it is the fundamental mechanism through which oppressive structures maintain themselves… We cannot understand caste without understanding the systematic violence that enforces untouchability. We cannot comprehend patriarchy without analysing domestic violence, sexual assault, [and] honour killings. We cannot grasp imperialism without examining genocide.”

Kandasamy: I think a lot of people defaulted to using the word ‘activist’ because to use words like ‘revolutionary,’ ‘radical,’ ‘militant,’ or ‘organiser’ would sound too leftist and too scary. It felt like a safe way of [addressing] people who wanted change [and] accountability, people who were organising and showing up at protests.

But I want to clear something up: The word “activism” has now earned a lot of bad rep because it has now come to be associated with someone with a degree in public policy, who works for an NGO, who takes home a hefty pay package, and has a career graph as competitive as any investment banker or software engineer. It has become like the word feminist—a lot of people might be feminist but would not want to be identified as such because of its several problematic associations.

The idea that you are suggesting here—that activism gets conceptualised as love in my body of work—I find very interesting, because I do not remember such a clear formulation from me. But I agree with you—we want to change the world because we love [it]—and the impulse to outrage (against oppression, destitution) comes from the inevitable tendency to love. They are inextricable.

In Tomorrow…, the “offering made to a lover” represents precisely this dialectic. The words function simultaneously as weapons against the capitalist-casteist state, as acts of care towards the revolutionary collective. This is not some displaced romantic individualism, but the recognition that comes [from] asking ourselves the question of how we work towards change.

Change can only come from understanding; you cannot challenge what you do not comprehend. A deep structural understanding and analysis is as important for revolutionary practice as is emotional investment in the liberation of the oppressed classes.

The blurring of personal and political reflects my understanding that under capitalism and casteism, there is no private sphere insulated from systemic violence. The family, marriage, sexuality—these are all sites where hegemonic ideologies reproduce themselves. In refusing to see the personal and political as two non-overlapping sets, I am following the Marxist insight that all social relations are class relations, mediated through multiple intersecting systems of oppression.

How do we understand intimacy? Intimacy is not forged only when we go on dates. It is also forged when people share their lives and their stories and their struggles in the hope that they can fight together against oppression. As a writer, being subjected to the immense love (say, someone telling you their whole life story because they trust your intent, they trust you), I cannot think of anything more intimate than that. How not to let it take centre-stage?

The Chakkar: In relation to a work’s form of production, what would you say is activism, and if the form itself can be considered an author, i.e., an agent of change, perhaps the opposite of ‘medium as the message?’

Kandasamy: Form itself becomes an agent of change when it disrupts the aesthetic conventions that serve ruling-class interests. The fragmentation in my poetry, the refusal of linear narrative in my novels, the meta-fiction which collapses the fourth wall—these formal choices challenge what the market takes for granted. At the risk of sounding very Leninist, revolutionary form creates possibilities for revolutionary consciousness.

The Chakkar: In my view, The Orders Were to Rape You, is also about exercising restraint in storytelling, recordkeeping without fetishizing gender-based violence. You were making a documentary, a visual-heavy tool, as opposed to a book form, which allows people to imagine for themselves. What sort of challenges were you faced with while writing violence?

Kandasamy: I choose to meditate on violence because it is the fundamental mechanism through which oppressive structures maintain themselves in India and globally. We cannot understand caste without understanding the systematic violence that enforces untouchability. We cannot comprehend patriarchy without analysing domestic violence, sexual assault, [and] honour killings. We cannot grasp imperialism without examining genocide.

The challenges of writing gender-based violence centre on avoiding both the fetishisation of suffering and the liberal tendency to individualize structural problems. In When I Hit You, the violence is never presented as personal pathology but as the logical extension of patriarchal ideology combined with a proclaimed Marxism, revealing how revolutionary rhetoric can mask reactionary practice when gender oppression remains uninterrogated.

“If you are from the global south, trauma is the only language that you are allowed to speak. Not theory. Not passion. Not discourse. Just trauma.”

Whether it was the visual medium (the documentary being shot) or the written medium (the essay that I eventually wrote based on the documentary), the fundamental tool (if we can call one’s outlook or allegiance that) is to maintain narrative control with the victim rather than the perpetrator.

The Chakkar: Given the rise of OTT platforms and the accessibility they offer, select actresses worry about how people will be able to consume the intimate scenes they’ll be performing for work as privately as possible. As such, the documentary you wanted to make never did get made (per my knowledge). Do you feel that had it been made, it could’ve cheapened the violence that you wanted to document?

Kandasamy: I do not do much work in the visual medium, but I have always felt that as a woman writer, you are consumed. Not necessarily in the act of reading the text itself, but in the way in which people project a parasocial relationship onto you. Especially in the realm of the digital, although my fears about the voyeurism and miserable curiosity to which I am subjected predate the era of social media. There is something about being a woman writer in India which puts you [in] this danger zone—without people having access to your image, your videos.

Your observation touches on crucial questions about the commodification of trauma under late capitalism, and I worry about that a lot. Especially if you are from the global south, trauma is the only language that you are allowed to speak. Not theory. Not passion. Not discourse. Just trauma. It is unhinged the way [people from the global south] are conditioned to make that [their] only way of negotiation with the white-western imperialist order. And yet, despite all this, I was firmly convinced that what happened after the genocide [of the Tamil Tigers and Tigresses at the hands of the Sri Lankan state], what happened to the female militants had to be told. This was rape in the service of an imperialist agenda, rape in the name of Sinhala chauvinism.

Visual media, especially in our current moment of shortened attention spans and algorithmic consumption, tends towards spectacularising everything. I was aware of the multiple pitfalls, as well as the pressing need to preserve anonymity. I do not think I would have allowed for the commodification of trauma, or for the sensationalisation of victim testimonies.

The Chakkar: You also note in the book that, as a journalist, you had already captured video testimonies of people to remember the Kilvenmani massacre. But for this project, you wanted your “subjects to have autonomy” and “did not want their words coming out filtered through a writer’s pen.” How did you ensure your pen never interferes in telling their stories?

Kandasamy: Where I could incorporate the visual, I have always sought to do it. Whether it is in my ground-reportage from Bastar for the last couple of years, or [while] covering the anti-Dalit atrocity in Dharmapuri a dozen years ago. I believe that if you are going to the site of violence, you try to capture everything about it—the image, the voice, the testimony, the sound, the way the air feels, the terror at night. Sometimes you do that because technology has been democratised (I had a DSLR; I have a smartphone), but also because if you do not show, critics sometimes deny anything that happened. It is not only the act of writing, but the work of documentation. I won’t renege on that.

How did I exercise restraint? I let their words sit on the page unedited. Without preface. Without my mediation. It involved multiple strategies: preserving the testimonial format rather than converting experiences into literary narrative; maintaining the multilingual nature of the testimonies rather than translating everything into standard English; and contextualising the stories within broader patterns of anti-Tamil violence rather than individualising them as exceptional cases.

In the end, it worked well (I meet young people who are reading it at university, diasporic youngsters reading it in a reading club), and I am moved. I feel I did the right thing. The tensions that you outline are alive and well—the Sri Lankan state is definitely lobbying; it does not want these stories of their war crimes to come out. But those were attacks I anticipated. Also, in India, the LTTE continues to be a proscribed group. So, I was endangering myself in telling these stories, but I would do it again, and again, because I do not want any complicity, any guilt that I did not act in the face of heinous rape, massacre, genocide.

The Chakkar: In When I Hit You, gender-based violence is documented strikingly differently, for the novel leverages humour whenever it can. In coupling the narrative humour of this novel, which is principally about systemic failures—caste, marriage, following an ideology, corruption, gender, masculinity, with rage, how did you manage to strike a balance between sensitivity and newness of the POV?

Kandasamy: Your assessment is precise. I think this usage of humour stems from two sources. When I used to get this question earlier, I used to be thrown off guard and never quite know how to answer it. I always felt, ‘Wow, so what did you find funny exactly!?’ And I realised that everyone noticed and talked about the humour in the book because to talk about the violence there, the belittlement, the disgracing—that would shatter your heart. I realised it was a way to engage with me without being patronising, and without engaging with the violence there.

It is now nearly 10-12 years since the first drafts of that novel came to be written, and now, with the benefit of distance, and having come to understand myself much better, I have to say that this comes from my instinct for self-preservation. I work on violence (of the state, of caste, of patriarchy) a lot, and when you are working with something so crushing, you need to ensure that your core, your vulnerability, your tendency to appreciate beauty, your hunt for happiness, does not go away. A large part of the humour comes from this instinct. To be happy, to be able to laugh, I think, is the most conscious thing a person can do. It supersedes even thinking. One must want happiness with an almost desperation because when you are a writer, you are drowning in melancholy by default.

“I use humour… to temporarily mask the enormity of horror about to unfold. Almost as if someone is holding a silk scarf against your skin a moment before they fatally punch you. Humour is like that sensation, that one moment of feeling alive before you feel dead.”

As a narrative device, I think I use humour the same way people use it with me as a topic of conversation. To temporarily mask the enormity of horror about to unfold. Almost as if someone is holding a silk scarf against your skin a moment before they fatally punch you. Humour is like that sensation, that one moment of feeling alive before you feel dead.

The Chakkar: Let’s talk about silence now. It seems one has been talking about ‘male rage’—albeit not in a way that could’ve prevented it—and there has been little acknowledgement of ‘female rage’ or ‘women’s wrath’—that, perhaps owing to lack of resources and independence, in most cases, they were choiceless and silenced themselves. Sometimes, women and queer people particularly happen to be living with the perpetrator, so they can’t maintain the writerly and physical distance in telling their own stories. Given this context, could you reflect on silence, self-censorship, and giving expression to silence that doesn’t perpetuate harm in any way unto oneself or others?

Kandasamy: Your observation about the historical silencing of female rage while valorising male rage touches on fundamental questions of subjectivity. Under caste/capitalism, women’s anger at their oppression is pathologised as hysteria, depression, or mental illness, while men’s violence is naturalised as biological inevitability or justified response to circumstance. This enforced silence serves multiple functions: it prevents the development of collective consciousness among oppressed women; it channels revolutionary energy into self-destructive rather than system-changing directions; and it maintains the fiction that existing arrangements are consensual rather than coercive.

Self-censorship represents a particular challenge for writers from oppressed communities, especially in the current moment in India. The state’s use of sedition laws, UAPA, and extrajudicial violence against writers creates constraints on expression, too.

The Chakkar: Be it the titles or the structures of your works—Tomorrow…, The Orders Were to Rape You, or When I Hit You—there’s this toying with the idea of arresting readers’ attention alongside an attempt to extrapolate a deeply personal story to talk about the failing of society, government, or country? Would you agree, and would you like to share your thoughts on the titles and organising your works to include either directly or indirectly all those who can be held culpable of the violence these works document?

Kandasamy: Yes to all the above. Broadly, all the title choices are just shock aesthetics to shatter bourgeois literary decorum. My next book is called Fieldwork as a Sex Object. I seem to be getting better at this!

On the organisational structure of my works: they move consistently from individual experience to systemic analysis because personal trauma under capitalism and casteism can only be understood through structural critique. Revolutionary literature requires revolutionary politics, and revolutionary politics demands unflinching analysis of the material conditions that produce suffering.

***

Saurabh Sharma is a Delhi-based queer writer and culture critic. They can be found on Instagram: @writerly_life and X: @writerly_life.