Kutch Express

Photo: Kinjal Sethia

Personal Essay: ‘Some lanterns burned outside this huddle of bhajans and stories. As kids, we kept close to the elders. It would be hauntingly dark outside this circle, and we pretended to conjure witches waiting in the inner rooms or imagined that the screech of the fruit bats was the call of the spirits.’

I am standing outside the Bhuj railway station at five in the morning, and already there is a long queue for the shared six-seater rickshaws. The Bandra Bhuj Express is one of the only two trains that connects Kutch to Mumbai. Even when I was a kid, I was warned by my mother to be careful on this train. Once onboard, Kutchi no longer works like a secret code, as it does in Goa, where I grew up. The scene outside the station is still the same. Dust floats under the tall streetlights, Drivers call out the names of different villages on their route. Passengers bargain for seats on the rickshaw with the shortest route to their village.

This has remained the land where things are named after their utility, and the six-seater rickshaw is still called the chakda, six in Kutchi. Waiting for my husband to find us two seats, I am taken back to that morning when I was here with Maa and sister for our Diwali vacations. Maa was searching for a rickshaw to Beraja, a village in the Mundra taluka of Kutch.

My grandparents, whom the entire family called Bai and Bapuji, would pamper us kids with home-made ice-cream, fresh fruity musk melon, and stories as we strolled along the Nagmati River. The river, and the broken parapets of a fort—built by the Jadeja clan which ruled Kutch from the 16th century to India’s independence in 1947—served as idyllic backdrops for evenings that would go on to exist only as childhood memories.

Bai-Bapuji’s house had a huge courtyard, tiny dark rooms leading into darker rooms, and floors plastered with cow dung. At nightfall, the silence was punctuated by the chuk chuk of lizards and owl hoots. In the mornings, Bai gave us fistfuls of jowar seeds to feed the peacocks and peahens. They came to the red tiled roof over the house, and if we sat very still, they jumped into the courtyard and pecked at the jowar on our palms.

Bapuji filled the courtyard with mounds of river sand. He taught us how to mix the right amount of water, make clay and shape tiny pots and vases. My cousins and I played in the shadow of the thick neem tree, climbed up its branches, and slid into Rupi Masi’s compound next door. She was not related to our family by blood, but she had earned the name of Masi with gestures laded with maternal authority. She had a cow, and every year there was a calf tethered to her gate. She plonked huge silver glasses of fresh milk into our hands, wiped the white moustaches off our lips with the end of her bandhani saree, and flashed a red-toothed smile.

While I reminisce about these holidays at Beraja, I am called to the rickshaw. We have our seats, in a packed rickshaw, passengers huddled together and their luggage precariously piled and fastened to the vehicle with ropes. And the stories begin. Who and why are each of us visiting, how it is important to stay connected to our roots, or how it is tragic that some families have completely forgotten their ancestral homes in Kutch. I listen to these stories, lulled by the dust whooshing past my window, staring at the windmills once we hit the highway.

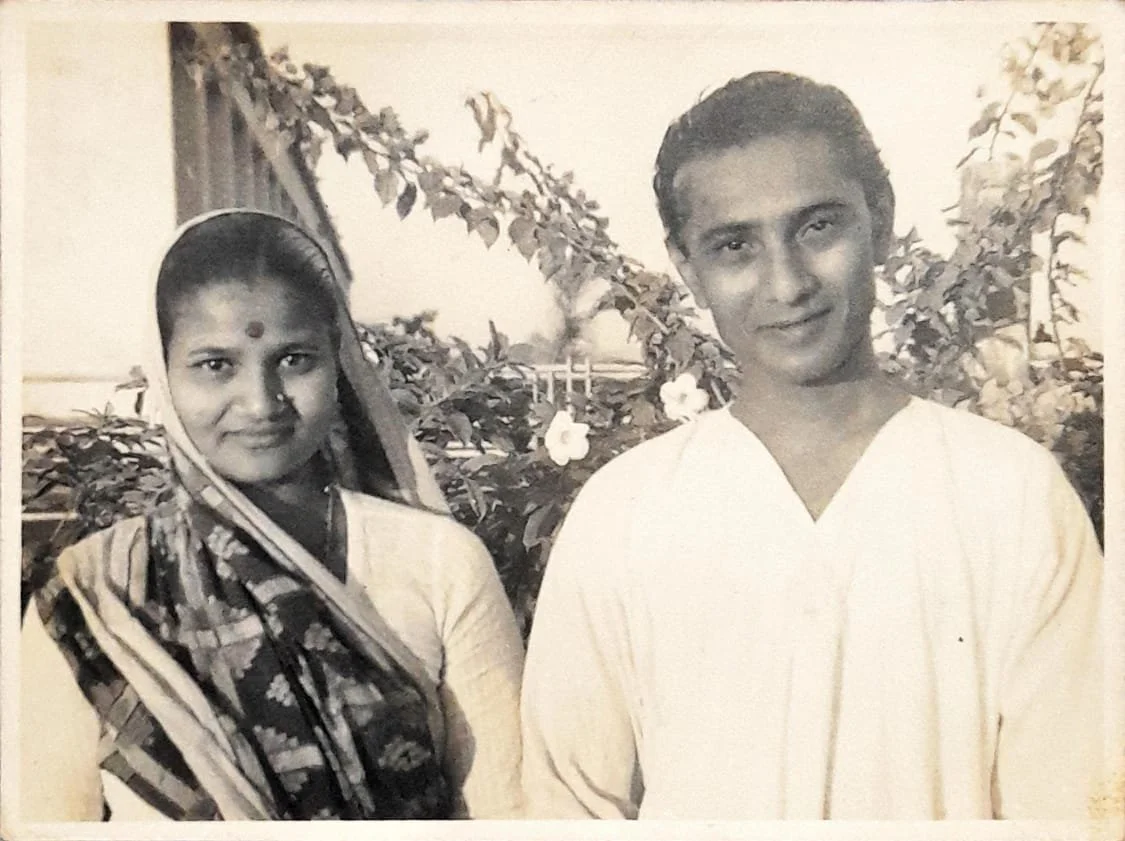

Photo courtesy: Kinjal Sethia

Bapuji’s courtyard transformed into an amphitheatre after sunset. The villagers gathered here every evening. Some waited for a call from Bombay; my grandfather was the only one with a telephone line. Married daughters called their aging parents, who would ask them when they would get the grandchildren back to Beraja. After the call, they shared the news with everyone in the courtyard. Khatu Bai’s son was working at L&T in Powai, Rupi Masi’s eldest daughter was married to a stock trader in Borivali, Heerbai’s daughter was studying to become a Chartered Accountant and interning at a private firm in Thane.

My cousins and I huddled on the string cots set up in the courtyard, listened for the toothy hiss of the lizard, the hooting owl, and gazed up at the stars on cloudless evenings. We listened to these stories. When the telephone stopped ringing, and everyone had finished rendering their stories for the last time, Bai went into the kitchen and made chai.

Bapuji was a silent presence amidst all these stories, but then he would break into an ecstatic voice when Bai brought in warm cups of chai. His voice broke the creaking of the cicadas, and he hummed “Bhala Hua Mori Gagri Phuti.” Some lanterns burned outside this huddle of bhajans and stories. As kids, we kept close to the elders. It would be hauntingly dark outside this circle, and we pretended to conjure witches waiting in the inner rooms or imagined that the screech of the fruit bats was the call of the spirits.

Water canals lead right up to the farms, and there are fuel pumps at regular distances. Business houses have chosen the desert as an idyll for power generation. Windmills rotate nonchalantly along the open expanses of scrub land and white salty swamps. There are few reasons left to return.

I am jolted awake as the rickshaw jumps off the highway onto the untarred dust road to Beraja. We are here to witness the initiation ceremony of a Jain monk. I steal away from the religious functions, walk the labyrinthine lanes, through different neighbourhoods occupied by communities of Jains, Thakurs, Muslims, goat herders, dairy owners, and farmers.

Today, the fort is a heritage animated with the families from the Thakurai clan living inside its crumbling walls. A buzzard flies across the Nagmati to roost on the dry acacia. The sky might have streaks of pink with the flamingos migrating in winter. But they are moving further away each year.

Some families have replaced their traditional houses with posh bungalows with electricity and water connections. Vacations to Kutch are more comfortable now. My mother’s family can’t seem to find it easy to replace the walls after Bai and Bapuji. The plumbing does not work, the wooden rafts in the inner rooms may have a termite infestation. I can hear the lizards, but the neem tree outside is lonelier. There are no owls or bulbuls in its branches.

Water canals lead right up to the farms, and there are fuel pumps at regular distances. Business houses have chosen the desert as an idyll for power generation. Windmills rotate nonchalantly along the open expanses of scrub land and white salty swamps. There are few reasons left to return.

Photo: Kinjal Sethia

Many of the houses damaged in the earthquake of 2001 have not been repaired. The children who called their parents on Bapuji’s landline first gave them mobile phones, and then most of them took away their parents to a more comfortable life in the city.

Broken walls, vine woven doors, stuck windows and shambled roofs make for aesthetic photo opportunities. As I sit in the dusty courtyard, alone, I feel the echoes from those evenings resound in the emptiness. The wind blows, shifts the dry neem leaves around, and I try to listen to some new stories. It feels like it is those same stories of loss, amplified, repeating. The same voices, which warn that if I forget those you left behind, then those who come after me won’t have any stories to tell.

There will be empty houses, broken roofs, loss, longing, and songs of virah. The villagers still wait for a phone call and news from Bombay. But now, the wait is emptier. They have fewer friends waiting with them. There are fewer doors where they can go to share the news. The closed and cracked windows open into courtyards infested with shrubs, snakes and time held stagnant.

Beraja is left bereft, stranded aside on the fast smooth expressways running from the port of Mundra to the white innards of this scavenged land. There is nothing left, no new stories, no Kabir bhajans that you can listen to while your grandmother caresses you into sleep.

***

Kinjal Sethia is a writer based in Pune. Her work has been published in nether Quarterly, Gulmohar Quarterly, In Parentheses, Bangalore Review, Tahoma Literary Review, Marrow Magazine, Singapore Unbound, Out of Print among other places. She is a Fiction Editor at The Bombay Literary Magazine and a co-founder of The Osmosis Poetry Prize. She is the recipient of the Vijay Nambisan Poetry Fellowship for 2025 and the Yosef Wosk VMI Fellowship for 2026. You can find her on Instagram: @kinjalsethia and X: @kinjalsethia.