The Politics of Female Longing in Fire and “Lihaaf”

In the art of filmmaker Deepa Mehta and writer Ismat Chughtai, Farah Ahamed explores themes of patriarchy, infidelity, and a testament to the desires of women.

Deepa Mehta’s Fire (1996) is the story of two unhappily married women, facing the storm of a quiet turmoil. The film shows the growing friendship and eventual sexual intimacy between Radha (Shabana Azmi) and Sita (Nandita Das), who are married to two brothers and live in a joint family. Fire illustrates its themes through scenes with muted colours, juxtaposing domestic interiors with the outside world. While the noise from the streets serves as a backdrop and a reminder of public life's regulated rituals, chaos unfolds inside the home. In a poignant moment, Radha and Sita watch a jubilant marriage procession on the streets below, their silence starkly contrasting with the music and dancing of the baraat.

Later in the film, Radha notes, “We all live in a house on fire, no fire department to call; no way out, just the upstairs window to look out of while the fire burns the house down with us trapped, locked in it.”

The film illuminates the destructive power of patriarchy and tradition, comparing it with passion and the desire for personal freedom. It depicts how homes—generally regarded as sanctuaries where submission and safety are presented as the norm—are in reality the opposite. The stifling atmosphere, conveyed through cinematic close-ups, illustrates how culture, religion, and politics constrain the lives of women, in the ordinary rooms of ordinary homes.

The question of their infidelity remains in the background, but pitted against patriarchy and tradition, their action takes on a complex nuance, asking: In such a situation, was it understandable and justifiable? The ability to feel deeply often requires immense courage and authenticity.

The film illuminates the destructive power of patriarchy and tradition, comparing it with passion and the desire for personal freedom. The stifling atmosphere, conveyed through cinematic close-ups, illustrates how culture, religion, and politics constrain the lives of women, in the ordinary rooms of ordinary homes.

Sita comments on the religious red dot on her forehead, highlighting her frustration at being controlled by societal expectations and customs: “Somebody just has to press my button, this button marked Tradition, and I start responding like a trained monkey.”

While infidelity is typically seen as morally wrong, particularly for women, forbidden desire can function as a profound political act against patriarchal oppression. This act allows women to reclaim their desires and challenge systems that deny their voices and needs.

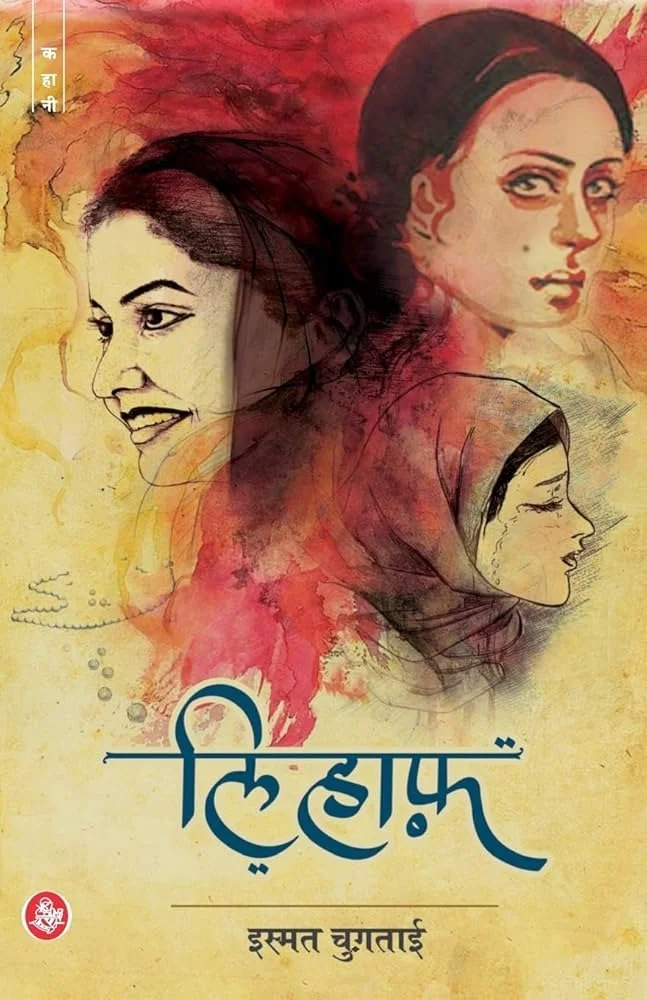

Radha and Sita stayed with me long after I’d first watched Fire, decades ago, as did their internalised discontent and female warrior spirits. Nearly 30 years later, I came across Ismat Chugtai’s 1942 short story, “Lihaaf” (“The Quilt”), translated from Urdu by Tahira Naqvi and Syeda S. Hameed. I immediately recognised an almost uncanny resonance between Chutgai’s story and Mehta’s film: Both explored female desire and agency as revolutionary forces in the context of patriarchal marriages. Echoing the domestic spaces of Fire, “Lihaaf,” is a story about the turmoil in Begum Jan’s bedroom. Although separated by fifty years, the two works shared a language of silencing, longing, and resistance, with the same underpinnings of claustrophobic traditions, strangled desires, and a yearning for affection and freedom.

In “Lihaaf,” Chughtai’s prose is delicate, suffused with suggestion and silence. Told through the point of view of a girl-child narrator, desire simmers beneath metaphors. Here the lihaaf is not just a covering but also a physical and symbolic barrier. It shrouds the affair between the lonely and unhappy Begum Jaan, married to a Nawab many years her senior, and Rabbu, her maid, with whom she develops an affection. Rabbu has no other duties except to massage Begum Jaan’s body with a “variety of oils and pastes for two hours” every day. Desire develops as a hidden, almost spectral presence in the story, one that whispers and shifts, revealing itself only through implication.

Unlike the nuanced, feminist desire explored in Fire, the choice of a child-narrator of “Lihaaf” allows Chughtai a layering of perspectives. This creates a tension between the narrator’s innocent gaze and the older, more complex world of adult desires. While the story provides extensive details about the narrator’s observations and experiences, she remains unnamed, making her childlike references more comic and uncomfortable.

The narrator describes the first time she sees Begum Jan and Rabbu displaying their affection:

When I peered into the room on tiptoe, I saw Rabbu rubbing her body, nestling against her waist.

“Take off your shoes,” Rabbu said while stroking Begum Jaan’s ribs.” Mouse-like, I snuggled into my quilt.

There was a peculiar noise again. In the dark Begum Jaan’s quilt was once again swaying like an elephant. “Allah! Ah!…” I moaned in a feeble voice. The elephant inside the quilt heaved up and then sat down.

The bedroom, ordinarily private, is depicted as repressive and a site of intense yearning that defies both societal and domestic constraints. The ‘elephant’ here is a metaphor for the illicit and forbidden desire which no one dares to speak about, but it is also about the silence around the mistreatment of Begum Jaan by the Nawab. The narrator’s childish comments are both shocking and comic.

The elephant started fluttering once again and it seemed as though it was trying to squat. There was sound of someone smacking her lips, as though savouring a tasty pickle. Now I understood! Begum Jaan had not eaten anything the whole day. And Rabbu, the witch, was a notorious glutton. She must be polishing off some goodies.

In contrast to “Lihaaf,” Fire stripped away the veil of suggestion, and made desire an explicit, visible, and undeniable force. The camera lingered on Radha and Sita’s every touch and glance. Mehta’s intentional employment of close-ups, light, and sound exposed their erotic chemistry. While Chughtai embeds “Lihaaf” with subtle hints, giggles, and muffled arguments, Fire is filled with open, light-hearted moments.

Begum Jaan’s bedroom in “Lihaaf” becomes a secret chamber where desire, once buried under societal expectations, is freed. The Nawab’s lack of affection and acknowledgement of her creates a vacuum where an alternative intimacy can flourish, even if it is concealed by the quilt.

In one scene when Radha and Sita go shopping for groceries, they bond over their mother’s sayings.

Radha: “My mother used to say that the way to a man’s heart is through his stomach. Apparently, it’s a great English saying.”

Sita: My mother says that a woman without a husband is like boiled rice, bland, unappetising, useless. This must be an Indian saying.”

Radha: “I like plain, boiled rice.”

Where “Lihaaf” relies on silence, Fire uses strong images and dialogue to narrate longing. Yet, despite these differences, both convey desire not just as a sexual act but as an existential awakening. In Uses of the Erotic, Audre Lorde expanded the idea of Eros. She wrote, “The erotic is a measure between the beginnings of our sense of self and the chaos of our strongest feelings.” Lorde described it as an internal sense of satisfaction that, once experienced, one knows they can aspire to, and from which in honour and self-respect, they can require no less of themselves. Indeed, one of the first indications in the film that Radha feels suffocated by her marriage to Ashok is when she escapes to the terrace to breathe freely and be on her own. Sita joins her to get respite from her own unloving marriage. The only time Jatin has sex with Sita is depicted as cold and clinical; he rolls off and falls asleep after saying she should not be frightened by a little blood. The image of her cleaning her blood off the sheets while Jatin sleeps is both shocking and moving. As Sita falls in love with Radha, she takes the first step towards physical intimacy and kisses her on the mouth. Although surprised initially, Radha responds to Sita’s kiss and realises her long-repressed desires. The sexual tension mounts, as does their enjoyable secrecy away from the constraints of culture and traditional norms.

In both Fire and “Lihaaf,” domestic interiors are presented as places of submission and repression but are transformed into sites of rebellion and reclamation. Begum Jaan’s bedroom in “Lihaaf” becomes a secret chamber where desire, once buried under societal expectations, is freed. The Nawab’s lack of affection and acknowledgement of her creates a vacuum where an alternative intimacy can flourish, even if it is concealed by the quilt. Similarly, in Fire, scenes in the kitchen, prayer room, and bedroom depict Radha and Sita’s resistance against the boundaries of tradition. In both the film and short fiction, home and the domestic are territories where women’s desires resist the walls of patriarchy.

In ‘This Sex Which is Not One,’ Luce Irigaray critiqued the domination of the male gaze, and of female desire being subordinated to male desire, only permissible through the mediation of men. She challenged the notion that the erotic gaze must be forbidden to women, and argued that women’s desire did not speak the same language as men’s, suggesting a fundamental difference in their expressions of eroticism. In both “Lihaaf” and Fire, the characters do not channel their longing through male figures. Instead, they assert their autonomy by claiming their desires and creating opportunities, literal and figurative, where their emotional and physical needs are acknowledged and fulfilled.

For instance, in Fire, during a game of buch, a version of hopscotch, Radha kneels to pick up the buch and notices a drop of sweat on Sita’s leg. She wipes it with her finger and tastes it; in response, Sita stoops and they kiss. In an interview, the director Mehta commented on the scene saying she found it to be extremely erotic, even with both characters fully clothed: “Fire is really about sensuality. For me, what you don’t see is far more erotic than what you see. I love eroticism, but it has to be subtle.” (Sidwa, 1997, p.79)

Infidelity, often seen as a moral transgression, is reframed in Fire and “Lihaaf” as an act of resistance. In Fire, Radha and Sita’s affair emerges from a place of emotional starvation, where love, intimacy, and personal freedom have been denied in their marriages. Similarly, Begum Jaan’s affair with Rabbu is not simply an adulterous act but an emotional survival mechanism, and an effort to reclaim her own body and heart. Arguably, their acts of infidelity are not moral failings but feminist gestures of defiance against the societal, patriarchal, and cultural structures that seek to control them.

In Fire, as Radha and Sita are preparing to leave, Sita says she was glad that Ashok (Radha’s husband) had discovered their affair. Their conversation sets up the conclusion of the film:

Radha: “It really doesn’t matter now, does it? I only wish it hadn’t happened by accident. I wanted to tell him.”

Sita: “What would you have said? ‘Goodbye Ashok, I’m leaving you for Sita. I love her, but not like a sister-in-law.’ Now listen Radha. There’s no word in our language that can describe what we are, how we feel for each other.”

Radha: “Perhaps you’re right. Seeing is less complicated.”

What Sita meant was that sensual love between two women, let alone two sisters-in-law, is taboo. There was “no word” for the bond they shared as two women who understood each other’s situations and shared physical desire and affection. Indeed, they had “no language” for such a relationship—and yet, Fire became a touchstone for discussions of queer and LGBT lives in India. By labelling the film as “lesbian,” it opened up an important public forum for debate about female desire and independence, visualising lesbianism as a possibility rather than a pathology.

Chughtai spoke to the constraints of an earlier, more conservative era of the 1940’s, and Mehta re-contextualises this intimacy for what she believed was a more liberal Indian audience of the 1990’s. Shared motifs of heat, touch, concealment, and resistance connect the two art forms, but while “Lihaaf” whispers under a quilt, Fire is bolder.

In another scene in Fire, on the night of Karva Chauth when Hindu wives fast and pray for their husbands, the two spouses in the film, Jatin and Ashok, are conspicuously absent. Sita goes to Radha’s room and the two women make love for the first time. Later, when Sita asks Radha if they did anything wrong, she replies, “No.” Her simple answer conveys how Radha no longer judges her life by traditional norms and obligations.

In Fire the kitchen and bedroom as intimate spaces, emphasise the smothering domestic atmosphere, underline the emotional depth of Radha and Sita’s relationship, and render their desire and love not as illicit but as deeply human. When Radha’s husband Ashok reminds her, “Desire brings ruin,” she retorts, “Brings ruin. Does it, Ashok? You know that without desire, I was dead... You know what else? I desire to live. I desire Sita. I desire her warmth, her compassion, her body. I desire to live again.”

Although told fifty years apart, Fire and “Lihaaf” both sparked outrage when they entered the public domain in their depictions of forbidden love, and how they dared to voice what patriarchy, religion, and culture had silenced. Fire provoked a backlash upon its release with protests on the streets and attacks on cinemas in India where it was being screened. The publication of “Lihaaf,” meanwhile, led to obscenity charges against Chughtai. She faced moral castigation for her unapologetic exploration of female desire. During the trial she was reprimanded because it was, “reprehensible for an educated lady from a decent family to write about them (female lovers).” However, Chughtai stood her ground, declaring that women had the right to speak honestly about their experiences.

In My Friend, My Enemy. Essays, Reminiscences, Portraits, (New Delhi: Women Unlimited, 2015, p.132) Chughtai described the courtroom scene where witnesses attempting to prove the story “Lihaaf” obscene were challenged by her lawyer. The witnesses struggled to pinpoint any specific words as offensive. One witness eventually cited the phrase ‘drawing lovers’ as objectionable and Chughtai’s lawyer interrogated the witness, questioning whether “draw” or “lover” was the offensive word. When the witness hesitated and identified “lover,” Chughtai’s lawyer argued that the term has been widely used by respected poets and religious texts, thus discrediting the claim of obscenity. The witness then shifted to argue that it was “objectionable for girls to draw lovers to themselves,” particularly for “good girls.” Chughtai’s lawyer continued to press the witness, leading them to concede that it might not be objectionable for “bad girls” to do so, and that Chughtai might have been referring to such “bad girls.” Ultimately, the witness admitted that while the content might be “reprehensible” for an educated woman to write, it did not fall under the purview of law as obscene. This exchange effectively defused the obscenity charge against the story.

Some argue that Fire was loosely adapted from Lihaaf. Whether or not it was a literal inspiration, Fire responds to Chughtai’s story on a deeper emotional level. Chughtai spoke to the constraints of an earlier, more conservative era of the 1940’s, and Mehta re-contextualises this intimacy for what she believed was a more liberal Indian audience of the 1990’s. Shared motifs of heat, touch, concealment, and resistance connect the two art forms, but while “Lihaaf” whispers under a quilt, Fire is bolder. In both works, the protagonists Sita and Radha, and Begum Jaan find solace in forbidden relationships, explore its limits and push against boundaries.

Mehta and Chughtai’s art are a testament to women’s desires which are personal and deeply political, and the voices of women who refuse erasure and long for freedom. As Radha declares to Ashok: “Without desire, there’s no point in living.”

***

Farah Ahamed has been published in Ploughshares, The White Review, Los Angeles Review of Books, The Massachusetts Review, World Literature Today, The Markaz Review, and elsewhere. She is the editor of Period Matters: Menstruation in South Asia (Pan Macmillan India, 2022), described by Book Riot as an “essential” book “about the female body that dispel[s] misconceptions.” She is a human rights lawyer and lives in London. You can read more of her work here. She is on Instagram: @farah_ahamed_writer and X: @FarahAhamed.