The Curse of Beauty: The last letter of Gopi Kishan Purohit, my grandfather

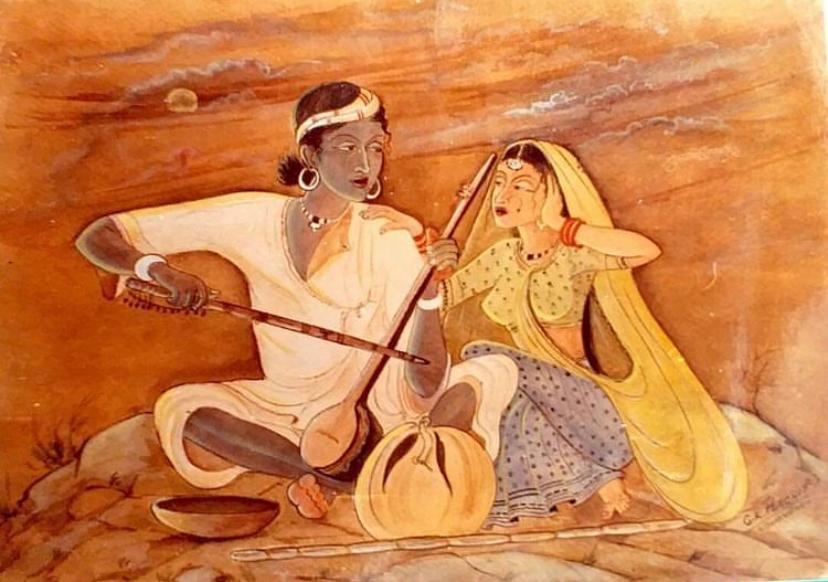

Photo courtesy: Aseem Sundan

Personal Essay by Aseem Sundan: ‘I remember both the man and his art as a montage of arbitrarily-arranged memories of all seasons and sentiments. Each unique in its way, some of them a fragment of his youth, some of his absurdity, some of his longing, and some just of beauty.’

“Sometimes when I cannot sleep, I get up and start painting. It helps me forget all my regrets, but it also makes me realize that at this age I cannot paint as I used to when I was younger, so I just make a lot of paintings instead of one good one. One for everyone who has asked me for my paintings for free when my hands were steadier.”

This is an excerpt from one of the last letters my grandfather wrote to me. My ninety-eight-year-old grandfather, Gopi Kishan Purohit, was among the last few miniature artists truly belonging to the Kishangarh school of art. Purohit—my Nanu—passed away peacefully in his sleep a year ago in an apartment in Jaipur, a city where he had lived for most of his life.

Photo courtesy: Aseem Sundan

I write this as I visit him for the first time since his death. I enter his room that no longer smells like the dampness of many a rainfall, or like years of disappointment hanging like his paintings on the walls. The colour palettes, paint brushes, old newspaper cuttings, soiled kurtas, dilapidated books, and letters to editors in envelopes with old glue losing its tenacity are all gone. It looks neat, like the vastness of green fields hidden in the mountains. I’m crushed to see that even his plastic chair—on which a cushion used to rest, waiting for him—isn’t around anymore, either. My grandfather, a man of many faults and a brilliant artist, has left this world like the winds of spring after breezing through the world all my life.

I stand and ponder the emptiness, the neatness, of the room he left behind. I try to find one particular painting of his, in which a woman in Ghaghra Choli sits in the cool shadow of a tree for a breather after fetching water from the well on a hot summer day in some village in Rajasthan. This painting always felt like a story of someone I might have known somehow. The sensation of a cold shadow on a hot day takes me back to the summer days of my childhood that I used to spend in my maternal home in Jaipur, far away and starkly different from our hometown in Jammu and Kashmir. In retrospect, I realize that the city of Jaipur exposed me to the many colours of the world outside of our little town.

This city, which played a major role to shape me into who I am today, has always been an embodiment of my grandfather’s paintings in one way or the other. There is no larger narrative to my numerous memories of Jaipur; instead, I get a glimpse of many shorter stories, haphazardly put together and placed on a plain wall, just like paintings are. Stories like those that my grandfather’s paintings often tell. Sometimes, random paintings placed together—like fragments of memory—make up for a feeling that I know but can’t describe, a feeling that has shaped me and my affinity for the beauty of the world itself.

I wonder where the art goes when the artist dies. Does it rid itself of the artist and become an independent entity that lives on? Or does it stay hidden in the almirahs, grieving over the loss of its creator, as most of my grandfather’s brilliant paintings do? Does someone find that almirah or that notebook one day and set them free to soar, or do dust and rust consume them like it did the artist?

A miniature artist by profession, my grandfather's youthful, steady hands were his only trusted companion. As the years flew by, however, his hands lost the moisture and steadiness that reaped the best out of him. His eyes, though, were still as sharp as a kite spotting its prey, camouflaging the colours of the world. And so, his keen eye for colours was still better than that of any young artist, even in his later years. After the summers of ‘98, he’d still stay up in the light of that one old study lamp, trying to fight the quiver of his hands, painting the most intrinsic paintings on small plastic canvases that he had to resort to in his late 60s (since ivory canvases were banned by then). He would stay up all night, painting and failing, like an old elephant losing its rich ivory teeth as the disaster of age and the demons of his past—hyenas and poachers—kept trying to prey on the canvases that lay before him.

He’d often say in the morning that he’d die with regrets. I wondered if it was merely a product of old age, or were the regrets that he held on to that made his hands quiver, turning his once so majestically-intrinsic paintings so ordinary in his last days.

In the days when he felt full of life, he’d send me to the offices of various newspaper editors with an envelope that had photocopies of his paintings, a list of the awards he had received in his lifetime, and pictures of him with famous people admiring his portraits of them. It made me think that, for an artist, perhaps nothing will ever be enough. Maybe this was the curse of being an artist: Having everything you ever created reduced to an envelope, seeking attention.

I often tell myself that even if I had nothing, perhaps, as a writer, I would always have my writing to sail me through whatever storm life throws at me. A pen and a notebook would be enough. But, when I see the room that looks nothing like him anymore, I wonder if my notebooks—like this place—will be washed away to a blinding neatness too. I wonder where the art goes when the artist dies. Does it rid itself of the artist and become an independent entity that lives on? Or does it stay hidden in the almirahs, grieving over the loss of its creator, as most of my grandfather's brilliant paintings do? Does someone find that almirah or that notebook one day and set them free to soar, or do dust and rust consume them like it did the artist?

My grandfather’s paintings hang in airports, hotels, and the houses of some famous people across the country—Amitabh Bachhan’s Jalsa, the Kishangarh airport, the palace of His Highness of Kishangarh, the Phool Mahal Palace hotel, and the homes of many others who purchased them at exhibitions. He has received the Rajasthan State Award. Indian prime ministers, from Nehru to Modi, wrote to him in admiration of his paintings. Articles about his art have been published in various newspapers and magazines through the years.

Photo courtesy: Aseem Sundan

And yet, before he passed away, he gave his daughter—my aunt—one last envelope and asked her to mail it to the editor of a local newspaper. He told her, “I promise this is the last letter I am asking you to send. Please send it even if I die.” He had repeated this numerous times before. There was nothing exceptional or special about this envelope, nor did he assign that it would be his last submission. Its finality was confirmed only when my aunt posted it, after his demise.

A part of me wants to get this letter back and hold on to it, merely because it was indeed his last, and it will end up in the same ditch as many others did. If I could have it back, I could keep it next to his painting of Bani Thani that graces my study table, along with the framed picture of him taking a four-year-old me to school on his Luna bike. At least, in my possession, this last letter would be valued as an artist’s final correspondence, to be savoured by another artist. At least, it would serve as a reminder to me of the artist’s curse, to keep fighting for their creation, forever struggling against anonymity.

It’s a vain, fruitless fight for you to be known by all, so your creations get what they deserve. A fight to create an association with your memories, your persona, so they don’t merely remain a thing of beauty hanging at an airport, a hotel, or someone’s home. A thing that can be traded around like precious shells that just appeared from the seas, but something possessed by someone as a fragment of you—the artist—along with the painting’s aesthetic brilliance.

A way for the artist to live on.

My grandfather remains with me as a fragment of those paintings. His paintings introduced me to his city, to beauty, to art, to imagination, to writing, to poems, to him. I cannot recall a moment since my childhood when I saw him and his paintings as different from one another. His persona mimicked his paintings: He’d tell different stories about his childhood, or his old friends over and over again to everyone around him, in a manner that would make an R.K. Narayan-like world of simplicity come alive. He would be a caricature you could laugh at or laugh with. His presence was like the smell of perfume that lasts in your senses—and your thoughts. He and his paintings were always each other’s extensions.

Photo courtesy: Aseem Sundan

I remember both the man and his art as a montage of arbitrarily-arranged memories of all seasons and sentiments. Each unique in its way, some of them a fragment of his youth, some of his absurdity, some of his longing, and some just of beauty. But as a whole, devoid of any crass judgment of this entitled world.

Sitting in this room, I remember when he sat next to me, reading his newspaper. I remember asking him how he had started painting. I remember him speaking about the friends he had lost during the Partition, and his days of playing squash. I remember him telling me how he learned the art of miniature painting, and how he used to stay up all night in front of the canvas so he could get food on the table for the family. How he used to go miles to give painting tuition to children born to better-off parents. I recall the story of him wooing my Nani, who had come from Karachi at the time of Partition. How she was the most breath-taking woman anyone had ever seen—his first tryst with beauty—and their union being one of the earliest love marriages post-Partition.

During the course of all these conversations, I remember thinking how my Nanu—an artist and a man of colours—struggled at the art of expressing himself in words. How his feelings, like those of most people, lacked any exactness when he tried to express them. Maybe that is why all those letters to the editors were pretty much the same. He was never quite able to tell them how he wanted the world to know him and his art.

So, I stand here in his room, collecting what is left of him in the air, his memories, and I feel that I—his grandson and a writer—exist as some twisted way of giving some precision to the expression of his life as an artist. I wish this letter to be considered my grandfather’s last letter, written by his grandson on his behalf.

My grandfather was an artist, like millions of other artists in this country—but he was better than most. He had neither the means nor the intellect to tell the world this, but if you look at his painting of a woman sitting by the tree with matkas of water by her side, taking a moment for herself on a summer day, her intricate henna-clad hands, the precision in her fingers and feet, the embroidery of her ghagra and choli, and the signature elongated face of the Kishangarh school of art, you’d be able to see a vision of his life in Rajasthan. You would see what his eyes saw and how intricately they saw it. How grass felt on his feet and how summer heat reminded him of that tree’s shadow. How matkas full of water relieved him, how a thing of beauty is born where you feel like you belong.

It’s a vain, fruitless fight for you to be known by all, so your creations get what they deserve. A fight to create an association with your memories, your persona, so they don’t merely remain a thing of beauty hanging at an airport, a hotel, or someone’s home

When you look at his paintings, you see his visions, his life, and his dreams, and in them, you find dreams of your own. My Nanu might not even be aware of this, but him being an artist might have been his misfortune, for it is unlikely that his paintings will carry a part of him with them as he wanted.

But the world will always be fortunate to have them, for they carry a certain beauty and inspire people who look at them to find beauty in their own lives, even create it, thus leaving the world a little more beautiful every time. And maybe that is the legacy of Gopi Kishan Purohit, and many others like him.

I hope that, if you ever come across a painting signed by his name somewhere, you remember him a little, that you encounter the humour and absurdity of his last letter. That in you, too, he is able to live on.

***

Aseem Sundan is a bilingual poet from Jammu & Kashmir. He has been published in poetry journals like Muse India and Scarriet Review, apart from a few anthologies. Poetry is where he finds freedom to write the truth that we hesitate to write in prose. You can find him on Instagram: @aseemsundan and Twitter: @aseemsundan.