A Call for a Postcolonial Education Revolution

In The Amateur (2024), Saikat Majumdar explores education, humanity, and inclusivity from different perspectives to highlight the major flaws of colonial education. The book asks for intensive correction in institutions and in the people’s psyche.

In a recent interview with Chalchitra Talks, the director, producer, and actor Anurag Kashyap spoke about the forgotten art of discovering rare books from roadside vendors. He suggests that privilege and fading curiosity prevent many contemporary readers from venturing toward offbeat, unexpected texts. Those who still do, he feels, rise above class and convention, guided by the sheer joy of discovery and the promise of something new each day.

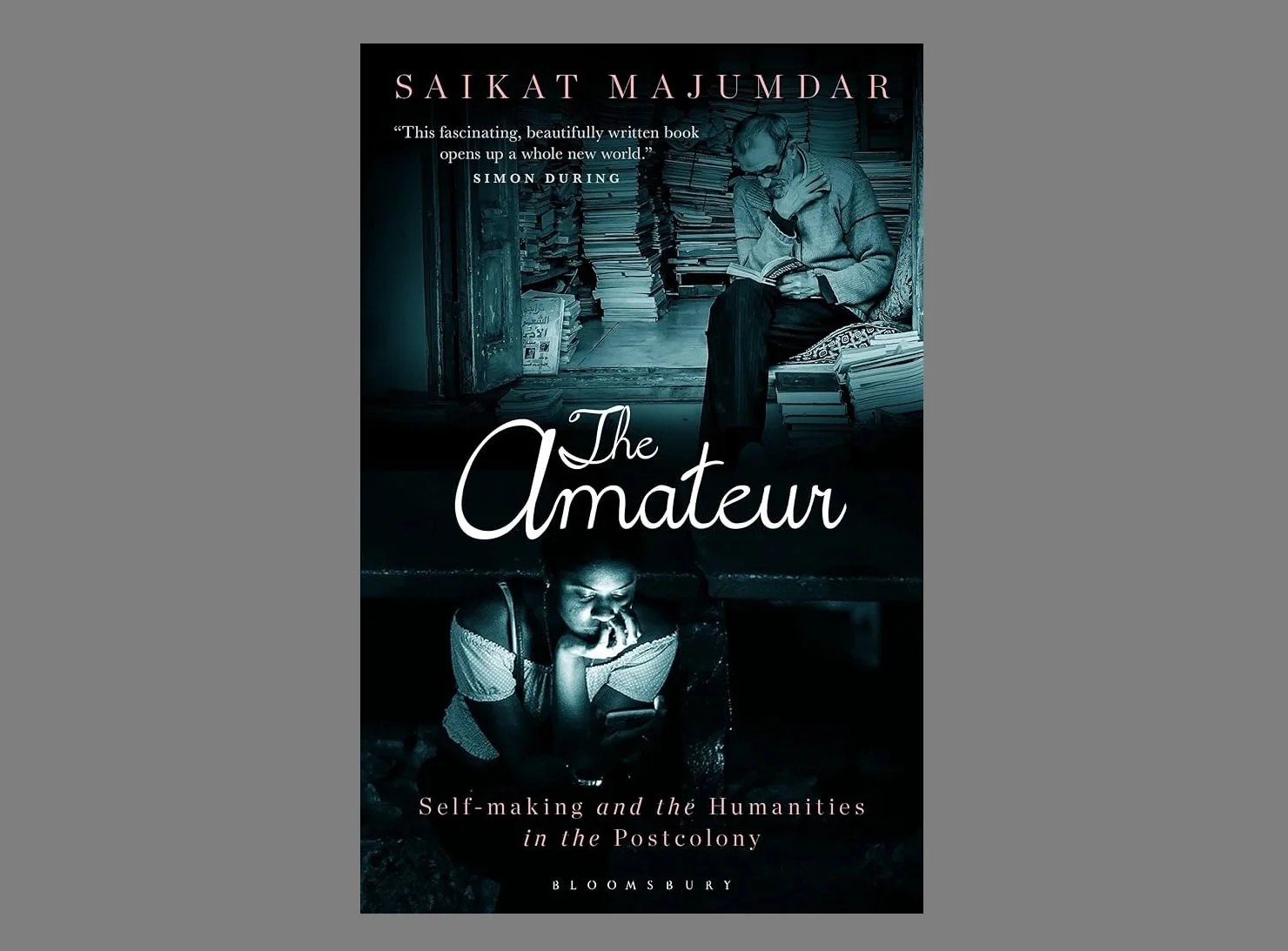

Such readers retain a rare innocence, remaining curious amateurs at heart. In his 2024 book, The Amateur: Self-Making and the Humanities in the Postcolony (Bloomsbury India), Saikat Majumdar posits the curiosity of amateurs against ‘corruptible’ conventional education, its institutions, and the binary approach of those who are the recipients of this framework. Divided into six chapters exploring education, humanity, and inclusivity from different perspectives, The Amateur highlights the major flaws of colonial education, and argues for intensive correction in institutions and in the people’s psyche.

In the chapter “The Colonial Map of Misreading,” the writer hits the first nail on the type of education colonised countries and their educational institutions are still following, without giving thought to the vastness of knowledge that is expanding with time. The word ‘misreading’ is a clever choice for the title, since coloniality or colonisers blurred our reading vision to hold us back and utilize our senses, leading to a misreading of individual behaviour in diverse societies.

Majumdar quotes the essayist Pankaj Mishra here, describing his own university life as “three idle bookish years at a provincial university in a decaying old provincial town” (2). Highlighting the devolution of education in India, Majumdar is curious about understanding the reason behind the acceptance of this form of education. He mentions that it might be because people wanted to be a part of a newly cosmopolitan world. Or it was propelled by the anxiety of staying unemployed in a bad economy after the British looted the resources of the colonies and left. And because it was the only option available, people not only chose it—they also passed it onto their offsprings.

Similarly, in other sections of the chapter, the writer has a bigger question to ask: If students from colonised countries read the subjects of the West, how are both going to treat each other? It is like a corporate scenario, where students from the provincial parts of the country find it difficult to adjust to companies adhered to cosmopolitan life, because the former prefers a colonial form of education which provides lesser skill sets to their students, ultimately making them employable parallel to the Western framework.

Majumdar enters the realm of academic study repeatedly to understand how the marginal, meandering and flawed cultures of reading can also become helpful in both authoritative and professional debates.

Through Derek Walcott’s poem “Another Life,” Majumdar brings to the forefront the imperial gaze that is distant from the lives of the natives, or the ones they colonised. Further, the writer brings before us Abdulrazak Gurnah’s reading of this particular poem, which made the latter think that he had to identify himself first, before the rest of the world saw him.

The second chapter “Poor reading, Weak theory” highlights the importance of reading and the major hindrances readers (of any age) face in real life. The question Majumdar asks is that if someone is not literate but wants to read, are the ‘rules’ of reading going to hold him back? When a book becomes just a material and not a tool of self-reflection and contentment, it doesn’t have to provide anything. But for curious minds, even the feeling of a book has a major impact since they know the purpose of words. Majumdar argues by writing, “the power of a particular kind of text eludes literacy and understanding even as it emphasizes the very bookishness of a text” (33). Here, he refers to Nathan Snazza’s reading of Tony Morrison’s Beloved, where the latter says that literacy is always about affects and not about chronological study.

The doctrine of joining literacy with reading is rudimentary since, according to Partha Chatterjee, literacy can be attained even by eavesdropping, but the effect it has can be termed “reading the people.” By quoting Chatterjee, Majumdar brings a different dimension of literacy. He also mentions that marginal literature has been documented mostly due to the absence of literacy. To adhere literacy with reading is an agenda of the privileged to control literature, language and its luxury. From Sant Kabir to Guru Nanak—the former being a mystic and the latter the originator of Sikhism—many great thinkers have documented their ideas in the absence of literacy. So, if in case of religion, absence of literacy is not considered a hindrance in the path of reading, why is it considered so important in other cases?

Majumdar is not against the spread of literacy. Rather, he is against the power and domination that comes with the subject. It lays down specific structures which many cannot follow because they have been laid down by the authorities of education. To strengthen this statement, Majumdar highlights J. Daniel Elam’s focus on readers who read only to construct a resistance against the authority and all its fundamental tools. Literacy, under colonial atmosphere, has always been an agent to dictate over the masses.

Elam in his book World Literature for the Wretched of the Earth (2020) argues that “reading could mark modes of refusal, non-productivity, inconsequence, non-expertise and non-authority” (37). He states that the writer’s stand is against the conventional understanding of literacy. Reading that belongs to the margins is often excluded from the mainstream for which translation has become a marketable genre at present. Majumdar enters the realm of academic study repeatedly to understand how the marginal, meandering, and flawed cultures of reading can also become helpful in both authoritative and professional debates.

The chapter that forms the fundamentals of this book is the third one named “Autodidactic Nation.” Most countries that have been colonised have to teach themselves about the culture they lost, the studies which were destroyed and the dreams that shattered. Majumdar’s concrete question is, “Why education becomes the most acutely sought after thing in communities that are most sharply deprived of it?’ (55) The writer gives the example of apartheid in South Africa which forced the educated Africans to take jobs which didn’t suit their profile. Yet they strived to garner knowledge because the absence of it bothered them.

Similar results can be seen in India as well, where most of the population earns a degree which does not align with the jobs they do later. Majumdar quotes Es’kia Mphahlele from his collection of essays The African Image where the latter writes, “it is a lonely man who is not taken seriously by his own people, yet cannot keep aloof from them and their daily miseries”. (56) The educated upper-class Indians drag down the economy of the country, which then subsequently also compartmentalises education, and cleverly disorients others from attaining their better selves. It is the depravity, the hunger, the absence, which most want to address in a poor nation.

In the chapter “Books, Roots, Pasts,” Majumdar gives readers a comprehensive overview of how education has been hijacked by the colonisers. But he does not limit to what happened in the past. The reflection of those past activities is cultivated in a better way by the present followers of both modernity and civilizational heritage. Indians, especially Brahmins, in the past have forced their educational domination over other sections of the society.

Majumdar focuses on on how the colonisers thrusted Christianity on Africans, which also speaks largely about the unitary objective of people in power. Just as the colonisers fabricated the culture of Africa, the Brahmins corrupted the texts of Hinduism to manipulate people from other strata of the society. More that religious texts, the Ramayana and Mahabharata are literary documents, but both the colonisers and Brahmins exploited the source of Indian civilization to reframe the past and convolute the present. Conventional education has never been able to break through this well-constructed wall of delusion and manipulation. It is through unconventional and rebellious ways that the reformers of this country brought the true form of the texts in the mainstream to magnify what stayed hidden.

The Amateur may be read as an academic text, but it is also a guide to understand how reading happens, how education should be approached and life must be studied. The book connects histories to formulate a single sky, in which many of these issues can be addressed without any discrimination.

Majumdar’s criticism of conventional education, the established constructs of reading, and accepting confabulation, should be given further attention, since we are on the verge of losing our history and basic educational rights. To transform our minds, we must comprehend the dangers we are living with and the horrors that await in future, especially in the advent of AI disrupting language, learning, and creativity. The book is a seminal addition in the area of literary criticism, which will be enriched if Majumdar’s words and ideas are implemented in practice.

***

Kabir Deb is an author, editor, content writer based in Karimganj, Assam. He works as a teacher in a government institution and has completed his Masters in Life Sciences from Assam University and is pursuing Masters in Creative Writing from The University of Oxford, London. He has been awarded with Social Journalism Award in 2017. He is a recipient of the Reuel International Award for Best Upcomimg Poet in 2019. He recently won the Nissim International Award for Excellence in Literature for his book Irrfan: His Life, Philosophy and Shades in the non-fiction category. You can find him on Instagram: @kabirdeb.zorba.