Innocence Lost: Sarvesh Wahie’s Poetic Lament for Mussoorie

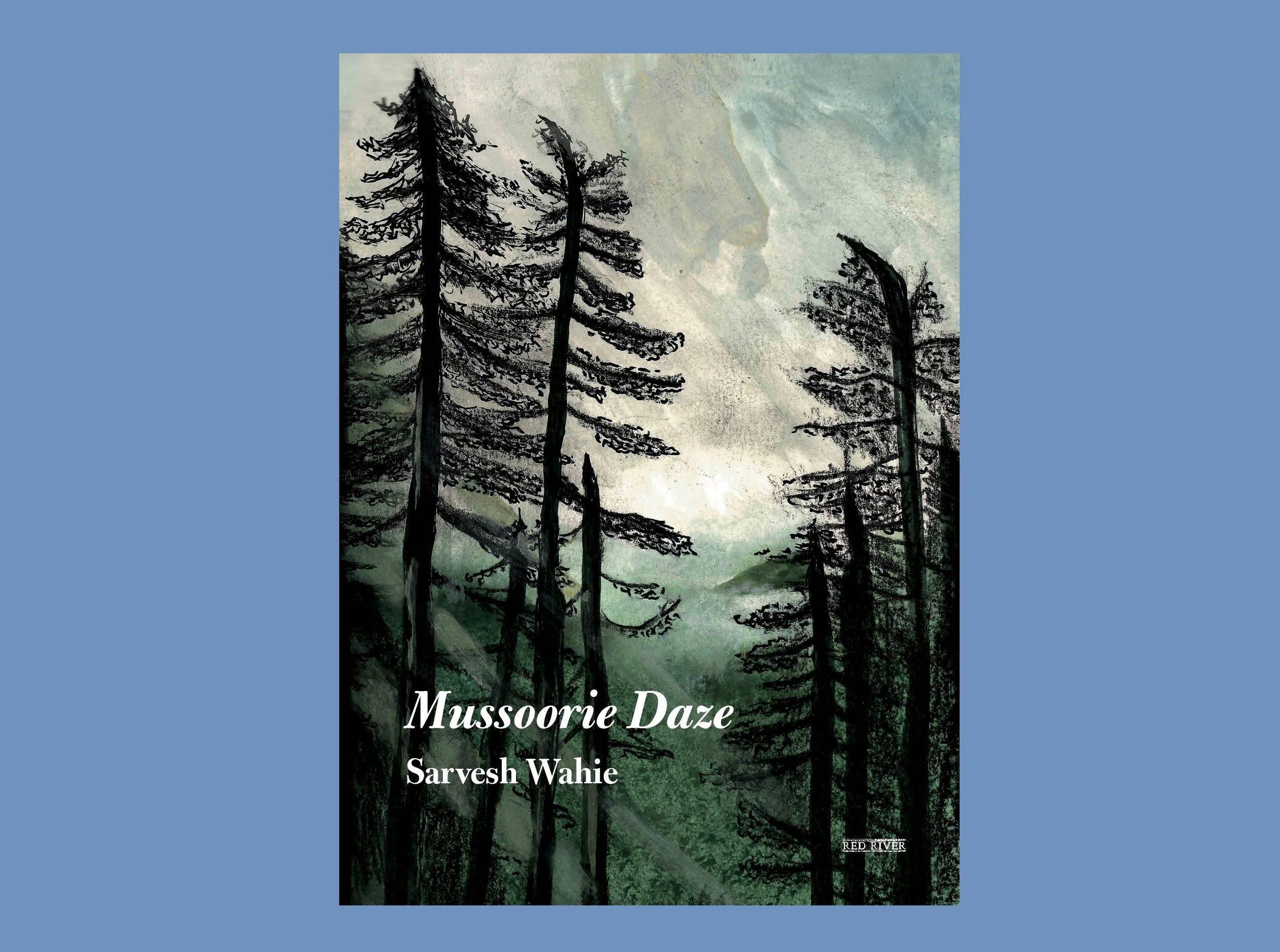

Written with understated, sublime beauty, Sarvesh Wahie’s Mussoorie Daze (2025) is a literary and philosophical text that examines the ontology of a lost Himalayan paradise, and the changing character of memory, self, solitude, and community.

Sarvesh Wahie’s independently published Mussoorie Daze (2025) begins with an ominous welcome to the titular, picturesque hill station, a reminder of nature’s losing battle against the onslaught of man. “There are more of humans and less of trees for sure,” he writes.

new buildings coming up instead of the law prohibiting construction. Noisy tourists, obsessive drunkards, and reckless youths. Bass booming hysterically outside smoky car windows and ruptured silencers lining the streets. Rocks are pillaged with jackhammers under the cover of darkness. (15)

Hailing from Mussoorie, Uttarakhand, Wahie is a Berlin-based writer, with eclectic interests in arts, music, and literature; accordingly, his latest volume combines elements of reportage, philosophical ruminations, and fiction. As the author Bill Aitken says in the foreword to the book, this ‘inspired unbridled ode’ to Mussoorie is “as recondite as The Waste Land and earnestly existential as Sartre.” (11)

At the heart of the book lies the inevitable fact that Mussoorie has been changing. In 2023, the town celebrated the 200th year of its founding. The ‘Queen of the Hills,’ has been a paradise for writers, retirees, convalescents, and occasional exiles, owing to its peaceful, and isolated surroundings as well as inspiring closeness to the Himalayas. However, in recent years, the hill station has undergone drastic and often damaging changes. A surfeit of tourism, and a ‘construction boom’ have contributed greatly to this phenomenon.

Tourism has doubled in the last two decades. Government data shows that around 10 lakh tourists visited Mussoorie in 2005. The number doubled up to over 20 lakhs in 2024. This seems to have created a catch-22 situation for the small idyllic town. Tourists are essential for its economy as a hill-station, but in order to accommodate and entertain their growing numbers, more hotels, restaurants, and parking lots are needed. While some new construction is understandable for this reason, the unscrupulousness of local builders, and mindless digging up of roads and well-known landmarks have agitated residents for quite some time now. Growing emissions from vehicles, cutting of trees, encroachment on public land, and other forms of environmental damage are all part of their concerns, as the Times of India reported earlier this year.

The mountains that surround it, the mist which hovers above it, the forests that fill its valleys and hills: all contribute to Mussoorie’s attraction for those who prefer solitude to company; silence to noise; the beauty of nature to the harsh materiality of concrete, metal, and glass.

Along with these factors, climate change has added another dimension to Mussoorie’s woes. The Guardian reported that an unprecedented heatwave in the plains in 2024 led to the surge in tourists. Even Landour, another Raj-era hill station close to Mussoorie, once considered an off-beat destination, is now overrun by domestic tourists.

The degradation of Mussoorie’s public spaces, owing to growing tourist pressure, and haphazard planning of public works and amenities by authorities, is noted by Wahie in the first chapter of the book, “Finding Silence”:

Why do you then ravage the heart of these Mussoorie hills? Fortunately, the tunnel project from Kingcraig through Hampton Court Convent up to The Mall was nipped in the bud. Rocks were raided nonetheless, and a new building now stands in adoration of its flouting manoeuvre, looking down upon the ever-expanding Doon valley. (23)

What is happening to Mussoorie is not unique per se. The violence that it is facing is the violence inherent in how our contemporary global polity is structured, especially in the era of globalisation. Since the 90’s, capitalist-style ‘development’ has been the norm, rather than the exception. It usually takes place by flattening the differences and uniqueness associated with any space since the goal is to make everything look like a suburb of an American or European city.

Along with sharp commentary on Mussoorie’s environmental degradation, the opening chapter introduces a parallel narrative about a relationship between the protagonist Prince and his beloved Mist. Both are free-spirited characters, arising from the author’s imagination, whose souls are bound to Mussoorie. They long to rise above the chaos that surrounds them, but they are unable to do so, and they bear this insurmountable tragedy with grace, beauty, and a touch of mystery. We do not know who they are, where they come from and where do they disappear. They are liminal beings, creatures of the twilight.

This relationship can be read as a metaphor for Mussoorie and its idyllic past, represented by Mist; Prince can be seen as a stand-in for the author, an admirer of its beauty, who longs for its ‘lost’ innocence; as one of the poems which accompany the prose says:

For there used

to be a land

where flowers bloom

pansies and tits play.

The forest was greener

waters gushed endlessly

and mortals would rejoice

the exuberance of a greener paradise.

The innocence you speak of, was lost. (29-30)

The second chapter, “Dreams Break,” is a long meditation on the nature of the Self. While the relationship between the Self and Time has been explored (in works like Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time) Wahie explores how the Self is affected by Space; and specifically, Mussoorie in this case. His philosophical investigation leads him to surmise that perhaps the Self is nothing else but an accumulation of memories, gathered through experience. Wahie writes, “If you could immerse yourself in an experience in a way that makes you forget who you are, you would realise that there’s nothing to take away from the experience except memories. And, the Self I own, hallowed in the fire of experience, is nothing but a stale memory.” (39)

Like every other Space, Mussoorie has its own uniqueness. The mountains that surround it, the mist which hovers above it, the forests that fill its valleys and hills: all contribute to Mussoorie’s attraction for those who prefer solitude to company; silence to noise; the beauty of nature to the harsh materiality of concrete, metal, and glass. But these experiences need to be replenished so that the Self is constantly recreated, like a flowing river. Otherwise, the Self grows stale and needs to be re-imagined by merging it back into Space.

Nestled among philosophical musings and fictionalised narratives are some sublime passages; observant and written with great felicity. Here is one describing a Himalayan woodpecker at work; what makes this passage special is the author’s ability to observe minute details of a natural phenomenon, coupled with vivid descriptive prose which describes the process step by step. Attention, in any case, is also a form of love. For Wahie, who loves Mussoorie, like Prince loves Mist, nothing that goes on in the town is insignificant. He sees it all, like a true lover notices every little thing about his or her beloved.

Yet, the Himalayan Woodpecker was the loudest here at the bridge, which connects the Kolti and Mussoorie ridges over the perennial Kolti Gad. Fixated onto the Rhododendron trunk, his continuous pecks reached the ears before the sight… Occasionally he would jump into the liminality of sun rays sieved fine through a thicket of the canopy above. It was only then that his red crown and crimson vent would glow. (37)

The third chapter is preceded by the poem “Daze 2,” which takes a more impressionistic view of Mussoorie and its residents, the bustle of the summer season, and the quieter winters when people talk to each other and tell stories. The poem includes a reference to the working class people through whose labour Mussoorie came into being and continues to exist.

In the chapter that follows, we witness Mussoorie in the winters, covered with snow. Just like the nature of the Self becomes intelligible in the second chapter, so is Mussoorie’s true nature revealed in this chapter, stripped of its forced existence as a hill station. In the winters, it reverts to being a place just like any other, where people worry about making a livelihood and children look for a place to play while their playgrounds are covered with snow. As perhaps the book’s most profound lines (and this reviewer’s favourite) say: “I feel snow reveals who we are…” (83); and later, “Snow cleanses the town with its white uniformity and makes everything appear, as it is, boundless.” (89)

The poem condenses the themes of the book into a sustained poetic interrogation and a re-imagination of Mussoorie and its various selves: its habits and hallucinations, its ghostly cemeteries and wild celebrations, its melancholic moods haunted by visions of far-away mountain peaks, the forests that surround it, and the beings that inhabit it.

The chapter also features a brilliant analysis of how the Self is like the snow, a kind of powder, held together by memories and experiences, prone to disintegration at the slightest touch.

The interwoven narratives bring an element of simultaneity to the text and give it the feel of a tapestry of impressions: Mussoorie comes alive in all its shapes and colours: its inherent spookiness, which has been explored in literary works such as those of popular local writer Ruskin Bond, the ubiquitous dogs and their nightly shenanigans, the shopkeepers, residents, school children, tourists, and more.

The last chapter “Existence Slips” is about how most of what makes up our Self, and what matters in our life is often an act of ‘slippage.’ We slip into taking some decisions, or having certain experiences; and sometimes, expressing ourselves differently than we had originally planned to. This is driven by both doubt and desire. Consciousness does not always guide our actions—other factors also exert themselves and create conditions for this ‘slippage’. Wahie writes: “The vitality of existence then shows itself in the form of a slip. Existence slips. A slip is that necessity of existence which brings all the characteristics of positions, situations, and directional movement in the vitality of utmost doubt and desire.” (123)

Ultimately, it all comes together. The circle is completed. Wahie’s Mussoorie lies beyond the noise: it is a state of mind, captured in silence. “Every now and then one hears the mountain scops owl hoot twice in regular intervals. This is the native sound of a Mussoorie night. A sense of belonging froths to the brink with his hoots. Silence thus, is acknowledged and homecoming is made possible.” (102)

The book ends with another ode to its eponymous hill town, a long poem reminiscent of the Beat poet Allen Ginsberg’s work. It mixes pathos— “Oh! lonesome sorrow that wakes in the afternoon”—with euphoria—“First light bulb / First multiplex / First of the firsts / We are all proud! / Mussoorie — You are the Queen!”. There is biting satire— “Who are you? / Fostering nostalgia industry / cross-legged on the table / pancakes from Chaar Dukan. / The lemon ginger tea / does not taste as good”—and lament–“What has become of you?” (131-134)

The poem, or the epilogue where it appears, condenses the themes of the book into a sustained poetic interrogation and a re-imagination of Mussoorie and its various selves: its habits and hallucinations, its ghostly cemeteries and wild celebrations, its melancholic moods haunted by visions of far-away mountain peaks, the forests that surround it, and the beings that inhabit it.

Mussoorie Daze is written with a quiet, understated, but sublime beauty. It is a text that is literary as well as philosophical, suffused with love for Mussoorie, its environment, its past, present and future. Though it focuses on Mussoorie, Wahie’s book addresses themes that are familiar to us all: Home and its always changing character, making us all exiles of memory; self, solitude, and community; dreams and the tyranny of day-to-day reality. Through describing the ontology of Mussoorie, Wahie describes the nature of the human condition itself: always in a flux, anxious for what is to come, and nostalgic for what has been.

*

Abhimanyu Kumar is a journalist and writer based in the Netherlands. He co-authored The House of Awadh: A Hidden Tragedy (2025) with Aletta Andre last year for Harper Collins, India. He has written for several Indian and foreign publications as a journalist. He has also published poetry and fiction. You can find him on Instagram: @garcia_bobby123.