From Meme to Mania: The Cult Resurgence of Lord Himesh

Photo: @saregama_official on Instagram

“Jai Mata Di, let’s rock.” Himesh Reshammiya’s career has come full circle: from topping the charts, to flops and cringe compilations, and back to dominating global rankings.

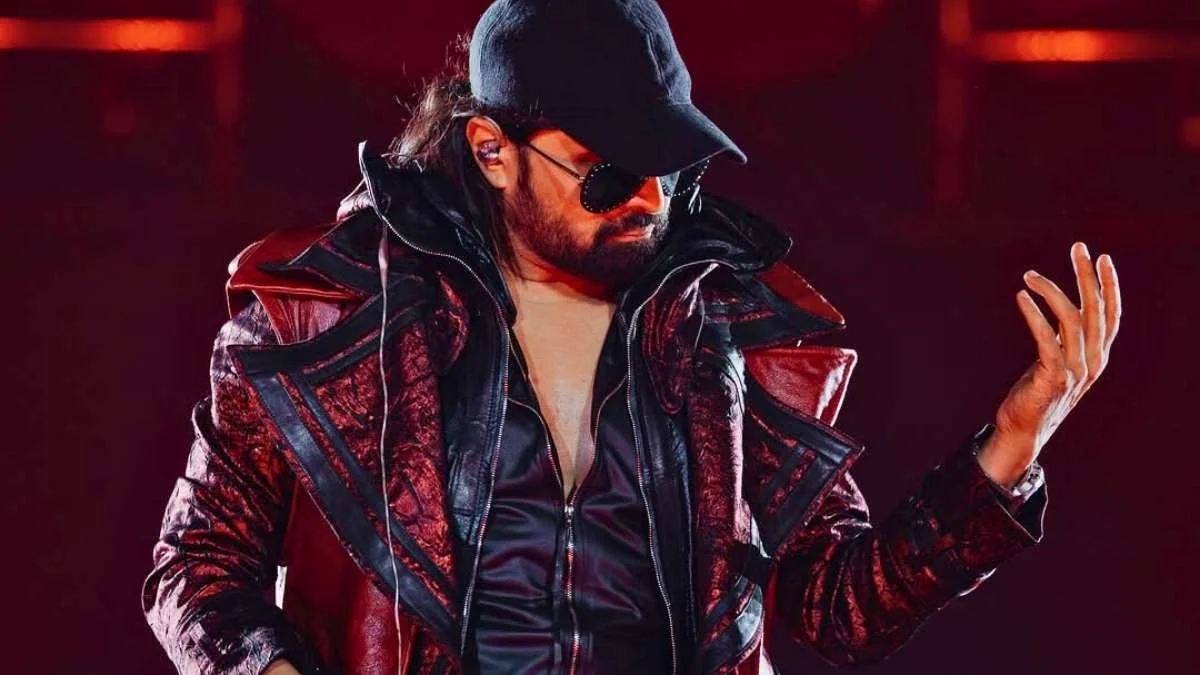

On a humid night this July, Delhi’s Indira Gandhi Stadium Complex looked like it had been overrun by a very specific cult, as thousands of people appeared in identical glittering red caps, ready to receive blessings from their leader. The lights dimmed, and the opening chords of “Tera Suroor” swelled out. The crowd roared, and out walked the Lord himself—his cape trailing, cap pulled low, arms outstretched like a man both in on the joke and owning it completely.

It was the man, the myth, the capped legend: Himesh Reshammiya. He is back, and he is ready to rock—or, in his own words: “Jai Mata Di, let’s rock.”

Tickets for Reshammiya’s 2025 Cap Mania Tour had sold out so fast that a second show had to be added. A little over a week later in early August, Bloomberg dropped its latest list of the World’s Most Influential Pop Artists Globally, where, nestled among Gen-Z Spotify staples, sat Reshammiya. For an artist long written off as a relic of mid-2000s Bollywood kitsch, the timing was poetic, like the third-act twist in a movie we didn’t know we were watching.

The man who was once memed and mocked for his “nasal twang” and unapologetic theatrics was now selling out stadiums and rubbing streaming-shoulders with Beyonce and Lady Gaga. It was as if the past decade’s jokes had simply paved the way for his comeback.

To understand why this feels like a cultural glitch in The Matrix, we need to remember the mid-2000s: an era when Reshammiya was Bollywood’s final boss. He wasn’t just singing the songs; he was the sound of heartbreak, clubbing, and inexplicably dramatic rain sequences. From “Aashiq Banaya Aapne” to “Jhalak Dikhlaja,” his voice was everywhere. It was the Age of the Suroor.

Reshammiya’s 2006 debut album, Aap Ka Suroor didn’t just dominate the charts; it rewrote them, selling a staggering 55 million copies worldwide, a figure that positioned Himesh Reshammiya alongside the greats of global pop of the time. To put that in perspective, Michael Jackson’s Thriller—the best-selling album ever—has sold around 70 million units. For an Indian pop debut—largely in Hindi—to even brush those figures was almost unthinkable. Aap Ka Suroor still stands as India’s best-selling album of all time. In an era before streaming and viral reels, music travelled through CDs, cassettes, and television countdown shows, and Reshammiya was everywhere, on FM radio loops, in auto-rickshaw speakers, and on late-night music channels. His signature cap-and-leather-jacket look became as recognisable as his nasal drawl, turning him into one of the most bankable and omnipresent figures in mid-2000s Bollywood pop culture. In that brief window, Reshammiya was more than just a music director or playback singer: he was a full-blown phenomenon.

But peak fame has a fast expiration. If Reshammiya’s mid-2000s music career was a Midas touch moment, his foray into films in the late 2000s and early 2010s was more of a Greek tragedy, minus the subtlety.

The man who was once memed and mocked for his “nasal twang” and unapologetic theatrics was now selling out stadiums and rubbing streaming-shoulders with Beyonce and Lady Gaga. It was as if the past decade’s jokes had simply paved the way for his comeback.

While the album was a runaway success, the 2007 film which inspired it marked the beginning of Reshammiya’s uneasy transition from chart-topper to screen star. Despite critical drubbings, the film managed sleeper-hit status, driven largely by fans curious to see their rockstar make his acting debut on the big screen.

The novelty, however, quickly wore off. Next came the film Karzzzz (2008), a reincarnation drama that was less “rebirth” and more “career speed bump.” The soundtrack did make a little noise, but the film barely staggered at the box office. Later titles like Radio (2009) and Kajraare (2010) failed to connect with audiences, either commercially or critically. Kajraare, directed by Pooja Bhatt, was embroiled in release disputes and barely saw the light of day, premiering only at a single theatre in Agra before vanishing into DVD limbo.

His later acting efforts, The Xposé (2014), and its equally baffling sequel plans, cemented the sense that Reshammiya’s onscreen presence was more curiosity act than bankable draw. By the mid-2010s, his film career had slowed to a crawl, his music chart positions had dwindled, and the industry seemed to quietly close the chapter on him as a leading man. The albums were still catchy, but without the films working, the songs stopped reaching the same audience.

Bollywood moved on, and so did the charts. Reshammiya’s compositions, once guaranteed chart-toppers, were no longer making the top five in annual rankings—a stark contrast to the mid-2000s when he had at least five to six songs dominating airplay simultaneously. His signature style, once fresh, now felt overplayed, overfamiliar, and ripe for parody.

And parody was the very next step: In the late 2010s, a new generation discovered Reshammiya not through his radio hits but through Facebook memes, YouTube edits, and Twitter threads. His 2000s music videos—once complete with leather trench coats, brooding stares, and inexplicable fog machines—were reimagined as surreal comedy. Lines like “Tera Tera Tera Suroor” took on an ironic life of their own, turning him into a cult internet figure. This was the time of the ultimate ‘Surroorgasm.’

Call it irony. Call it affectionate satire. It was a meme page that gave Himesh Reshammiya a dazzling second life. Launched first on Facebook, the Surroorgasm account curated remixes and meme edits centred around his Reshammiya’s trucker cap, his heavy-lidded gaze, and dramatic flair—each post part parody, part homage. On every edit, reel, or cryptic lyric snippet is both a wink and a salute, mockery meets admiration. The question embedded in its ethos: Is this cringe, or is it iconic?

Adarsh, the founder of the page, speaks with a mix of pride and affection about the role Reshammiya has played in his life—and, in a way, the role he’s played in Reshammiya’s. A self-proclaimed Reshammiya scholar and lifelong fan, he jokes that he’s practically part of the singer/actor’s family. “I’ve been watching him so closely, digging into such obscure corners of the internet for research, that it feels like I know him personally,” Adarsh says.

A self-proclaimed Reshammiya scholar and lifelong fan, he jokes that he’s practically part of the singer/actor’s family. “I’ve been watching him so closely, digging into such obscure corners of the internet for research, that it feels like I know him personally.”

Surroorgasm began as Adarsh’s attempt to carve a space out for his musical tastes. “Back in the era, listening to western music is what earned you the coolness brownie points. I could not relate to that. That’s was around the time I was reacquainted with our very own rockstar, Himesh.” The page now has over 148K followers on Instagram.

“There was no longer any discourse around the Indian music scene, it was no longer cool. I wanted to bridge that gap, make cringe cool again,” he recalls. By then, Reshammiya had drifted out of the mainstream, reduced largely to judging reality shows. He was still producing music, but the hits no longer dominated conversations the way they once had. Against this backdrop, Surroorgasm was born. “I had an unconventional fanpage. Instead of simply admiring the songs, I took on the route of humour. I compared Himesh to western favorites, using the lingo which was more culturally favored.”

The page was a hit, and gained a lot of followers quickly. It was somewhere around this era when Reshammiya got rebranded as a cultural icon. His nasal music which had been labelled cringe, started to become cool again. The butt of the joke was now the ‘Lord,’ and what was once cringe was now playful irony. “It was delightful for me to be at the concert and see so many posters calling him Lord Himesh. I came up with that!” Adarsh beams proudly.

By 2017, Himesh had quietly slipped onto Instagram, and his feed was nothing short of a fever dream. Think whacky selfies, pouty gym clips, and post-workout slow-mo videos that felt like they belonged in an alternate cinematic universe. That same chaotic energy birthed Himesh Doing Things, a fan account that rejected the airbrushed seriousness of celebrity culture and instead leaned into the absurd. The posts were hilariously mundane yet oddly profound: “Himesh as the back of an Indian truck,” “Himesh walking diagonally,” “Himesh after getting his aura cleansed.” These clips encountered Reshammiya beyond the music or the movies anymore, and found Reshammiya as pure, unfiltered content: dopey facial expressions, dramatic hand waves, everyday snack breaks, all recast as memeable performance art. Suddenly, he wasn’t just the man with the cap and the nasal voice; he was a living, looping GIF in India’s collective internet feed.

So, when the film Badass Ravi Kumar hit theatres in February 2025, it was Himesh Reshammiya’s self-aware wink at his own internet persona. The movie took his leather-clad, shades-wearing, slow-motion swagger and turned it up to eleven. It was camp, it was chaotic, and it was hilariously Himesh. As even the trailer suggested, in Ravi Kumar-verse, logic is optional. By playing into the very clichés that memes had mocked for years, Reshammiya reclaimed the jokes about himself. Audiences walked out quoting lines, not because they were profound, but because they were deliciously over the top. Meme pages clipped fight scenes, added ironic captions, and flooded reels with “Ravi Kumar” edits. What could have been another forgettable flop instead became a cultural in-joke, and Reshammiya was in on it.

That self-parody cracked open a new kind of fan energy, one where irony and admiration could coexist. And when the Cap Mania Tour rolled around in July this year, the ground was already primed. The same people who laughed at Badass Ravi Kumar were now queuing for tickets, wearing replica caps, and belting “Tak tanana Tandoor Nights” like a stadium anthem.

The tour is a rare full-circle moment for the performer: the meme character in the movie blurred into the real performer on stage. From the legendary “regular gaaun ya naak se” quip to christening his concert zones with tongue-in-cheek names like the “Badass Pit” and the “Suroor Zone,” Himesh has learned to lean into the very jokes that once mocked him, and in doing so, he’s claimed ownership of the narrative. Badass Ravi Kumar proved to be a dress rehearsal for the comeback.

The internet, in a twist only pop culture could pull off, reframed the very quirks that once earned him ridicule into symbols of unapologetic camp. Slowly, the mockery became affection, and the affection turned into genuine admiration, setting the stage for this unlikely tour. Part of this resurgence is generational: For millennials, Himesh is pure nostalgia, the sound of first ringtones, FM dedications, and college fest anthems. For Gen Z, raised on meme culture, he embodies the kind of self-aware cringe that loops back into cool. And for everyone else, he’s simply fun, proof that sincerity, however nasal, survives mockery. At a concert, all three audiences stand side by side: one singing from memory, one chanting in irony, and one just vibing.

Reshammiya career has come full circle: from topping the charts, to flops and cringe compilations, and back to dominating global rankings. In a culture that moves at the speed of a scroll, few artists get a second act. Reshammiya is now on his third—and for once, everyone’s in tune.

***

Himanshi Aggarwal is a freelance journalist currently pursuing her Master’s in Journalism at AJK MCRC, Jamia Millia Islamia. Her interests lie in stories related to politics, human rights, and social issues, though she also enjoys exploring social media, pop culture and art. She also loves music, cats, and flowers. You can find her on Instagram: @byemanshi.