India’s AI Governance Guidelines are here—But what of the Publishing Sector?

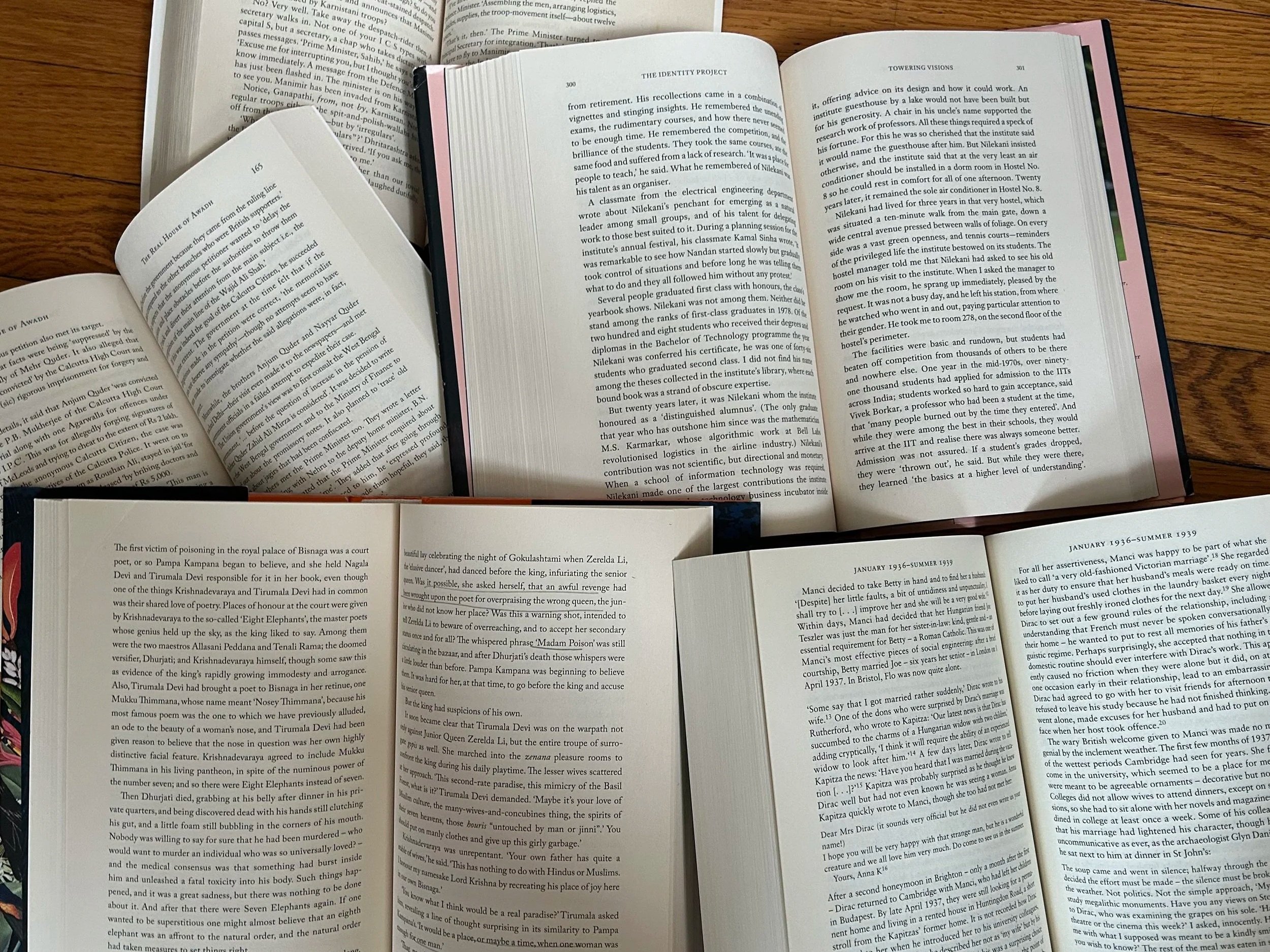

Photo: Karan Madhok

Without clear regulatory mechanism against AI data mining, Indian publishers have begun adapting ‘voluntary frameworks.’ Madhuri Kankipati argues for the urgent need for the AI governance guidelines to set legislation and protect creative workers in a multilingual, digitally expanding nation.

When the casual reader leaves through the first pages of a new book, they might not necessarily notice the copyright page. This early section is often reserved for the attention of authors, translators, publishers, cover designers, and others who worked on bringing that book to life. Usually in fine print, it features administrative details like ISBN, date of publication, publisher’s address, imprints, author’s email address, and copyright and piracy warnings.

However, some books released from late 2024 to 2025 have begun carrying another note as add-on to this list, directed at AI companies and the larger systems of machine learning—a note against using the content of the books for training artificial intelligence. This detail is seen in some recently released books in India, such as Searches by Vauhini Vara (Pantheon Books, 2025), On the Banks of the Pampa by Volga (HarperCollins India, 2025), and Mother Mary Comes to Me by Arundhathi Roy, among other new 2024-2025 releases from HarperCollins and Penguin Random House.

Is is not a coincidence that a considerable number of titles across different genres, published by two of India’s biggest publishing houses, inserted these clauses carrying copyright-page warnings against text and data mining (TDM) and training artificial intelligence systems. These are the practices Indian publishers had already begun adapting before the India AI Guidelines called for ‘Voluntary Frameworks.’

India has recently launched its AI Governance Guidelines (2025), a document that frames ethical design and seven principles: trust, people first, fairness, accountability, explainability, safety, and innovation over restraint. It is a need of the hour intent. Yet, when measured against the practical needs of writers and translators, whose labour is used as datasets for LLMs, the guidelines leave a gap. The guidelines suggest drawing ideas from India’s Digital Personal Data Protection Act [DPDP Act, 2023] and anchor AI ethics in user rights, privacy, and consent. The DPDP Act protects personal data, names, identities, and biometrics. A novel, a poem, or a translated work does not fall under an individual’s ‘personal data,’ even as it is creative labour: an output of time, skill, research, and layered nuances. When LLMs rely heavily on the work of writers and translators, India AI Governance Guidelines majorly focus on user privacy. It leaves out those whose work requires more protection mechanisms.

Another important distinction that is often observed missing from Indian AI policy and content discussions is defining the boundaries between AI-assisted writing and AI-generated content. AI-assisted writing involves human authors using AI as an assistive tool for formatting, editing, and proofreading, where the creative control and the core idea remain with the human author. These are the scenarios where non-native English writers are not limited to their small-scale demographic but their reach is expanded globally.

On the other hand, AI-generated content by contrast to the former is autonomously generated by the LLM from ideation, through research, writing, and editing. It is this category that raises copyright and creative labour concerns since it is vastly trained on copyrighted datasets, most of which is done so without author’s consent or any compensation. This regulatory absence is now visible in the new copyright pages.

Vara’s Searches was originally published in the UK by HarperCollins, which means its copyright infrastructure follows the EU Digital Single Market Directive (DSMD) Article 4(3), which gives writers the right to explicitly ‘opt out’ of text and data mining for commercial AI training. This clause is binding under EU law: If an author opts out, the AI developers must not scrape or reuse their text. However, when Searches carries this clause in Indian market, its value is reduced to a mere line, unenforceable and as helpless as any other Indian-published title because of the lack of any equivalent TDM legislation or opt-out mechanisms, and no statutory requirement for AI developers to honour reservations made by rights holders.

Similarly, HarperCollins India’s On the Banks of the Pampa by Volga includes a clause referencing the EU DSMD despite being produced and distributed within Indian legal jurisdiction. It signals that major publishers like HarperCollins are doing what they can because Indian law is not yet equipped for AI-era copyright harms.

While titles from HarperCollins borrow the provisions from the EU Digital Single Market Directive 2019/790, under Article 4(3) to prohibit AI training that is unenforceable in India, Roy’s memoir from Penguin Random House takes a more grounded approach with a simple one liner that says ‘Please no part of this book may be used in any manner for training AI technologies or systems.’ on the copyright page. It is a direct acknowledgment of the absence of any Indian legal safeguards.

India’s Digital Personal Data Protection Act protects names, identities, and biometrics. But a novel, a poem, or a translated work does not fall under an individual’s ‘personal data,’ even as it is creative labour: an output of time, skill, research, and layered nuances.

The Indian Copyright Act 1957 contains a ‘fair dealing for research’ exception, but this provision was drafted when LLMs or algorithms did not exist, leaving a gap for AI developers to argue that scraping or using copyrighted material as a dataset to train the language model falls under ‘research.’ But when the output is used commercially, the ‘research’ label cannot be applied. Even if it is being used for purposeful research as such in practice, it is still illegal and unethical in cases when the rightful author is not compensated. There are no Indian laws that require dataset transparency, opt-out registries for authors and licensing of copyrighted books for training LLM datasets.

The India AI Governance Guidelines 2025 acknowledge that Indian copyright law may need amendments, but they do not offer any regulatory mechanism, even enforcement, penalties for the copyright holders. Currently, the Indian AI governance guidelines serve as ethical principles rather than legal protections.

The deeper issue here is not whether models reproduce sentences, it is that LLMs can replicate the voice and style of the author as well, presenting itself as a cautionary threat when a piece generated by the AI is misattributed to the author and poet Meena Kandasamy in a university syllabus featuring a poem that she had never written. That explains Kandasaamy is one of the many voices and verbatim the LLM has been trained on. This fear is not limited to Indian writers but it is a global issue in all creative fields, from The New York Times’ case against OpenAI to the ANI, FIP vs OpenAI lawsuits.

In the era of genAI content, a Licensing Mechanism is the most direct protection the authors and translators can wield. Under a state enforced licensing system, AI companies must obtain explicit permissions before using the copyrighted material for training their LLMs. This mechanism ensures proper attribution, rightful compensation allowing the AI developers to understand which material is legally allowed for them to use, and what is off-limits.

Along with Licensing Mechanisms, India also needs a TDM opt-out policy modelled on the EU’s DSMD Article 4(3), that carries writers’ autonomy to even deny any and all permissions with respect to AI training. It also needs a mandatory transparency documentation for all foundation models trained on Indian data: the contributors, the materials used, and the rights aligning with the India AI Governance Guidelines leaning on the accountability and explainability factors.

The emergence of these warnings across multiple recent books is only the beginning of this pattern. While none of the DSMD clauses offer any protection in Indian jurisdiction, publishers and authors still adopting it signals that this is the beginning of a self-defending copyright page. For now, these practices may act as decorative shields, what India must do is establish AI governance that includes the publishing and content fields. Guidelines can set intentions, but only legislation can protect creative workers in a multilingual, digitally expanding nation.

***

Madhuri Kankipati is a reader, writer, translator and independent researcher based in Khammam, Telangana. Her work explores the intersections of literature, culture, gender, pop culture and technology. She translates between Telugu to English, with a particular focus on women writers. Currently, she is independently researching the impact of GenAI for Indian publishing, authorship and creative labour from a policy perspective. Previously, her writing has appeared in Borderless Journal and Muse India. She also runs an Instagram account completely dedicated to arts and literature: @withlovemadhuu.