A Bombay That Demands More

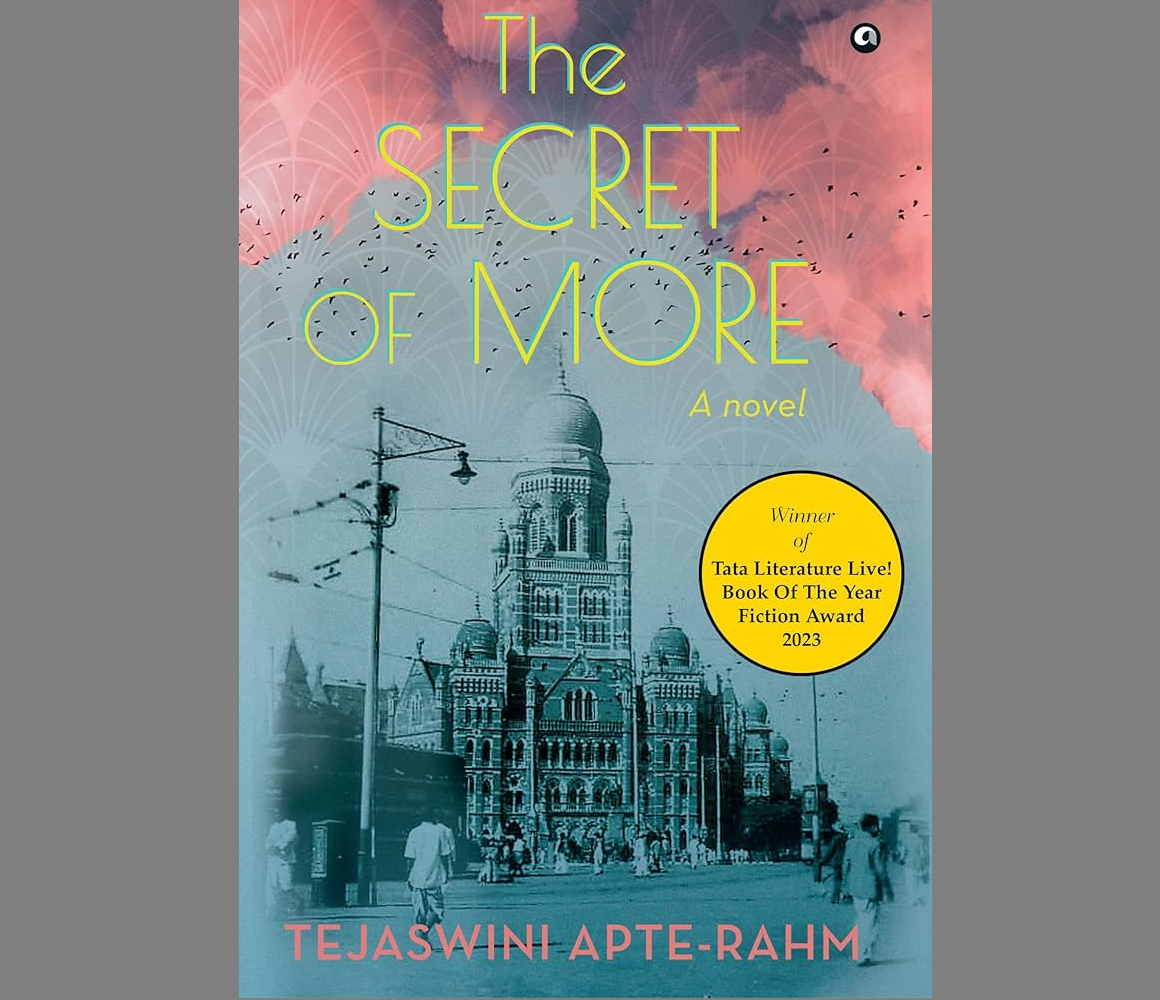

Tejaswini Apte-Rahm’s The Secret of More (2022) tells a provocative tale of urbanization in early 20th-century Bombay.

Bombay, a city of dreams, a city that never sleeps, a city that keeps transcending its boundaries, a city that’s always hungry for more. One doesn’t tire of reading about this megapolis: be it Rushdie highlighting its cosmopolitan complexities in Midnight’s Children, Jerry Pinto taking us through the lanes and parks as a young boy explores the city in The Education of Yuri, or Jane Borges shedding light on the lives of Goans and Mangaloreans looking for a safe harbour and livelihood in Bombay Balchao.

This is a city that demands to be written about.

Added to these literary forays of the city is The Secret of More, Tejaswini Apte-Rahm’s debut novel. The Secret of More tells the story of a 17-year-old Brahmin boy, Tatya, who goes to learn textiles-trading in Bombay and never looks back. He doesn’t have generational wealth, only a hunger to learn. If anything, even at the age of 70, he is eager to look forward in life rather than surrender to his fast-approaching death.

Set between 1899 and the 1950s, Apte-Rahm shows us a Bombay succumbing to the business of moving images and talkies, as Tatya becomes a big and renowned businessman, his investments ranging from textiles, iron and steel factory, bioscopes, and a theatre. The Secret of More was shortlisted in the JCB Prize 2023 and received the Book of the Year Award in fiction at Tata Literature Live 2023.

Set between 1899 and the 1950s, Apte-Rahm shows us a Bombay succumbing to the business of moving images and talkies, as Tatya becomes a big and renowned businessman, his investments ranging from textiles, iron and steel factory, bioscopes, and a theatre.

From the advent of the story, the debut author makes her seamless writing style evident. The narration relies heavily on the dialogue to educate the reader, while also informing the characters in the scene. For example, in the early pages of the story, we come across Tatya learning the trade of being a selling agent in the Mulji Jetha market as a Zaveri’s apprentice. Apte-Rahm describes the process of trade—from mills to market—in excruciating detail. However, instead of turning it into a third-person narrator informing the reader, she makes it a question-answer session between the teacher and apprentice.

The conversation seems natural. If one were to walk into the market on a particular day, towards seth’s pedhi, then this scene would not be out of place. Only the visitor won’t be privy to the conversation like the reader is in this text. The dialogue then informs the progress that the character has made since we first met him, as someone entering the market with a recommendation letter along with information about the trade.

This use of dialogue moves the plot forward alongside the narration which showcases the inner thoughts and conflicts of the characters. It also, sometimes, compliments the dialogue in expressing the changes that have taken place in the characters’ lives.

He made his way to the tap behind the dark chawl to wash his feet, and cursed just as cool water splashed over him. He truly was a fool, no better than a goat that blindly heads home on instinct.

Khatryachi Chawl was no longer home, had not been for the last two months.

He turned back the way he had come and trudged to the new apartment in Jamshedji Mansion on Sandhurst Road, a few minutes away. His wet feet squelched in his slippers and he left streaks of water all down the road like a wading bird walking awkwardly on dry land.

In this passage, we are informed of Tatya’s disappointment and self-loathing of having invested in a business that he knew nothing about. He is a selling agent of textiles; for sentimental reasons, he turns to bioscopes against his better judgment. Simultaneously, the passage also tells us that his textile business has grown enough for him to move out from the two small rooms of the chawl to a new apartment in the neighbourhood, marking his progress towards urbanization.

The details of the historical fiction help the reader process the changes in Tatya’s life from 1899 to the 1950s. This is not merely seen in his moving from Khatryachi Chawl to a 5BHK in Jamshedji Mansion to a bungalow, Greenglades, but also through Radha’s use of the household objects—and occasionally, her apprehension to do so. When first confronted with a water purifier, Radha denies letting it be placed in her kitchen. These little changes bring the question: Was Bombay growing, or was Tatya’s influx of finances making things more accessible for him? The answer, perhaps, is both. In the beginning, we see Radha’s discomfort with having to shift from using lamps to electric lights. In the end, we see Tatya’s delight at having mangoes in January, thanks to the refrigerator.

Tatya and Radha hail from a Brahmin Marathi family, following the traditions and rituals of purity, living in an all-Brahmin chawl. Tatya’s growing business shakes up Radha’s world, for she cannot fathom mixing with Anglo-Indians or Indian families in which women go across the city when they move to the apartment. In his trade, Tatya works with people of all castes and class, including Englishmen. The change in his surroundings don’t baffle him.

Despite his suggestion, Radha is hesitant to invite non-Brahmin, non-Marathi women to the house for the haldi kunku. She decides to host it on the terrace which allows her to socialize with the wives of Tatya’s colleagues without having to bring them inside the house. Throughout the novel, there are such instances where Tatya is more considerate than Radha. Be it letting his sister-in-law return to school for matriculation after being abandoned by her husband, or letting Radha visit the royal family in the neighbourhood upon their request. These changes happen slowly, and in limits as women are allowed education but not the pleasure of watching films outside.

It seems that men engage with the changing world outside the house and hence, seem to be more accepting that the women who believe that a woman’s role is to be a good housewife.

Tatya remains an endearing character throughout the novel. He isn’t blindly in search of more but he makes a Faustian bargain anyway. He invests, cautiously, in the bioscope business, knowing no ‘decent’ man from a respectable family should indulge in theatre or moving images. If this shadow on his heart wasn’t enough, he is bound to hire the actress Kamal Bai for his production house to remain in competition with the rest of the industry.

The presence of Kamal Bai turns the shadow into a blemish on his heart, as Tatya falls for her without ever being able to acknowledge the intimacy between them. He grows to appreciate her experience in theatre, her ideas to expand business, and the fact that she doesn’t behave as if she is ‘beneath’ him. Kamal Bai is all that a ‘decent’ woman shouldn’t be. Despite his inability to completely accept her role in his life, Tatya grows in the bioscope industry enough to own a theatre.

Apte-Rahm skilfully balances Tatya’s world outside and Radha’s domestic space. She goes to great extents to showcase what a self-respecting married Brahmin woman should be like, with the help of texts such as Majhe Avaate Pustak and Gharatli Kame, which are presented as go-to guides for housewives. The real education of young girls happens within the household when they learn to prepare various traditional Marathi delicacies, to clean different utensils in different ways, to prepare and store pickles, so on and so forth.

The gender roles are clearly divided in the Brahmin household. The men go out to study and work. The women stay in to take care of the household. They don’t go out; nor, apparently, do they aspire to. The norms are so strictly observed that when a letter for Radha arrives in the Khatryachi Chawl, her neighbour Lele Mavshi keeps it till Tatya returns from work. It implies that the outside world doesn’t touch the domestic space without the husband’s approval. When Tatya opens a theatre, the women of the household visit the theatre for the opening puja and do not stay to watch the opening show.

Durga becomes the amalgamation of the hard-working and resilient women who came before her. She forges the path for the next generation, walking out of the conservative household without leaving their values and traditions.

It is only when Durga meets her neighbour, Gitanjali, the princess of Sonpur who has moved to Mumbai to study in St. Xaviers’ college, that she begins to see a new perspective. It comes as a surprise to Durga that education could be a priority, considering she was good in studies. Yet, she doesn’t defy her parents when they pull her out of school to get married.

Gitanjali talks about Anandibai Joshi, the first Maharastrian woman doctor, and Kashibai Kanitkar, Maharashtra’s first woman novelist. This piques Durga’s curiosity. Through the interaction between Gitanjali and Durga, Apte-Rahm mentions the changing lives of women. She introduces the changing Marathi society through the small royal household, where widows don’t shave their hair and women are given higher education.

Durga becomes the amalgamation of the hard-working and resilient women who came before her, like Radha and Kamal Bai. She is the beginning of the bridge between Radha’s domestic haven to Kamal Bai’s struggles in public spaces. She forges the path for the next generation, walking out of the conservative household without leaving their values and traditions. She doesn’t allow her physical disability make her less deserving, and stands up for herself when the time comes. The women in Apte-Rahm’s work display great strength, and, irrespective of their circumstances, they survive.

Outside the household, we’re in a time in the early 20th century in India filled with historical landmarks in the national struggle for independence. Apte-Rahm carefully showcases the impact of the British hold in India by describing in detail the ascend of King George in Mumbai in 1911, only to question it later as the news of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919 hits the newspaper stands. The World War in between is mentioned as a pause in Tatya’s trade, leading to losses and the decision to invest in an iron and steel factory.

The political events are cautiously chosen considering the caste and class of the protagonist. For example, there is a depiction of horrifying violence after Gandhi’s murder by Godse, a violence directed towards Brahmins, and hence, deeply affecting the family.

Apte-Rahm’s craft interests the reader more in her description of the growing business of movies in Bombay, in her marvellous visuals of the organ that becomes the highlight of Tatya’s theatre, and in ways that she brings twists and turns to the plot just when it begins to seem predictable. Unlike Faustus, Tatya doesn’t sell his soul to the devil. He stops at just a blemish on his heart. Bombay, however, grows, and it accepts the talkies.

In The Secret of More, Apte-Rahm shows us a world where people will come and go, and their desires may fluctuate. But Bombay… Bombay will never stop; it will always want more.

***

Akankshya Abismruta is a freelance writer and book reviewer. Her reviews are published or are forthcoming on Scroll, Purple Pencil Project, Feminism In India, Women's Web, and Bookish Santa, Asian Review of Books, and Deccan Herald. You can find her on Instagram: @geekyliterati and Twitter: @geekyliterati.