Solvyns’ Bengal: The Etchings and Ethnography of an 18th Century Artist

Image courtesy: DAG

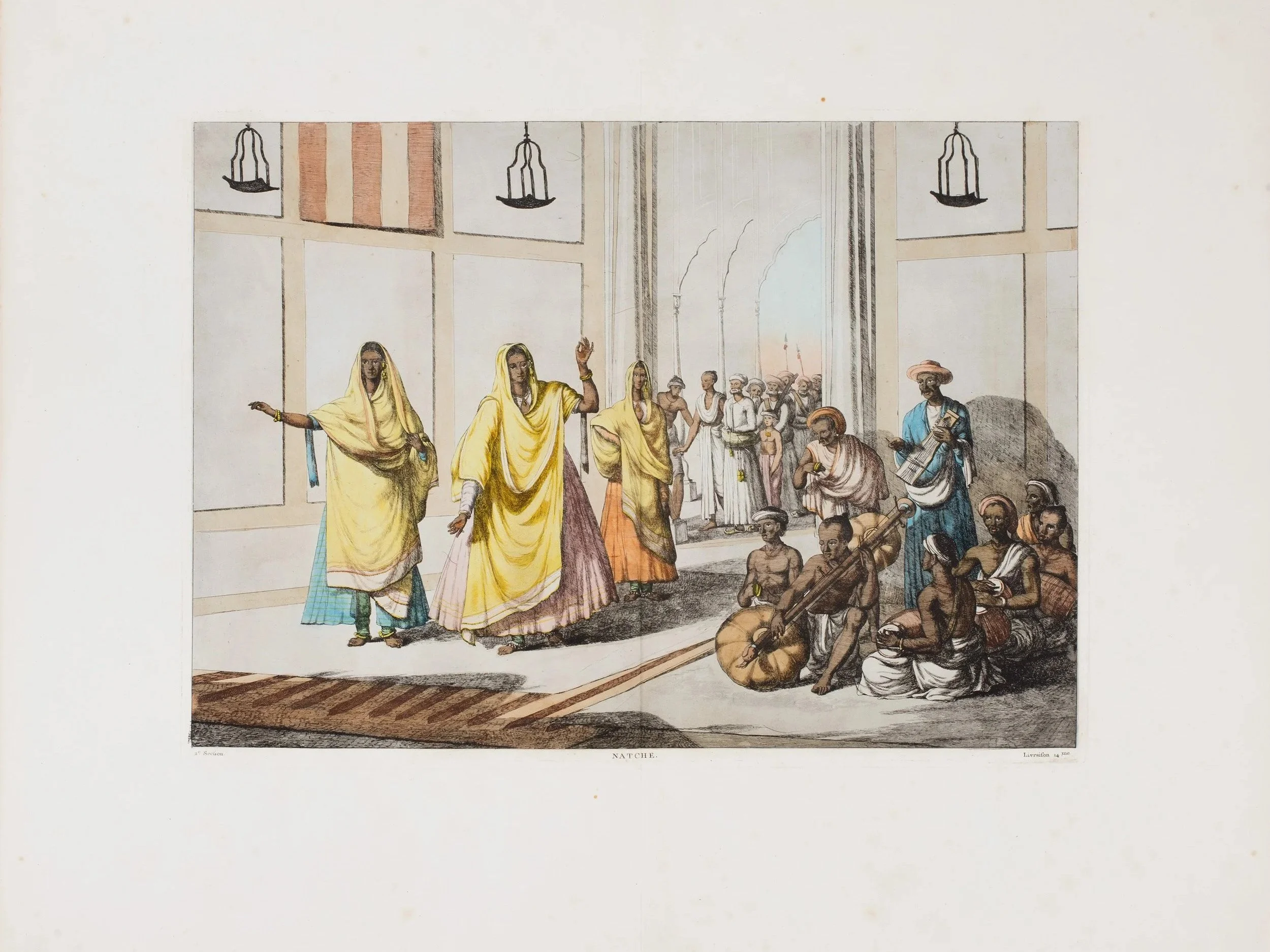

A multi-city exhibition of the work of Flemish marine artist François Baltazard Solvyns showcased comprehensive visual records of the people of Bengal, displaying the deep roots of caste and patriarchy in everyday life.

When the 18th-century Flemish marine artist, printmaker, and ethnographer François Baltazard Solvyns (1760-1824) began his ambitious artistic project in Calcutta, he could hardly have known that his work would become one of the earliest and most comprehensive visual records of the people of Bengal. At a time when Bengal’s later political culture—particularly under the Left Front government (1977–2011)—minimised caste, fostering the myth of a “casteless” Bengal, Solvyn’s etchings show how deeply caste and patriarchy were entrenched in everyday life.

In a multi-city exhibition People of Bengal: Coloured Etchings of Baltazard, organised by DAG (Delhi Art Gallery) Museum and curated by Dr Giles Tillotson (Senior Vice President, exhibitions and publications at DAG), the range and depth of Solvyn’s works depict the reality of caste in Bengal. The exhibition travelled to Delhi (2021), Mumbai (2024), and finally Kolkata (July 2025) at the Alipore Jail Museum.

Image courtesy: DAG

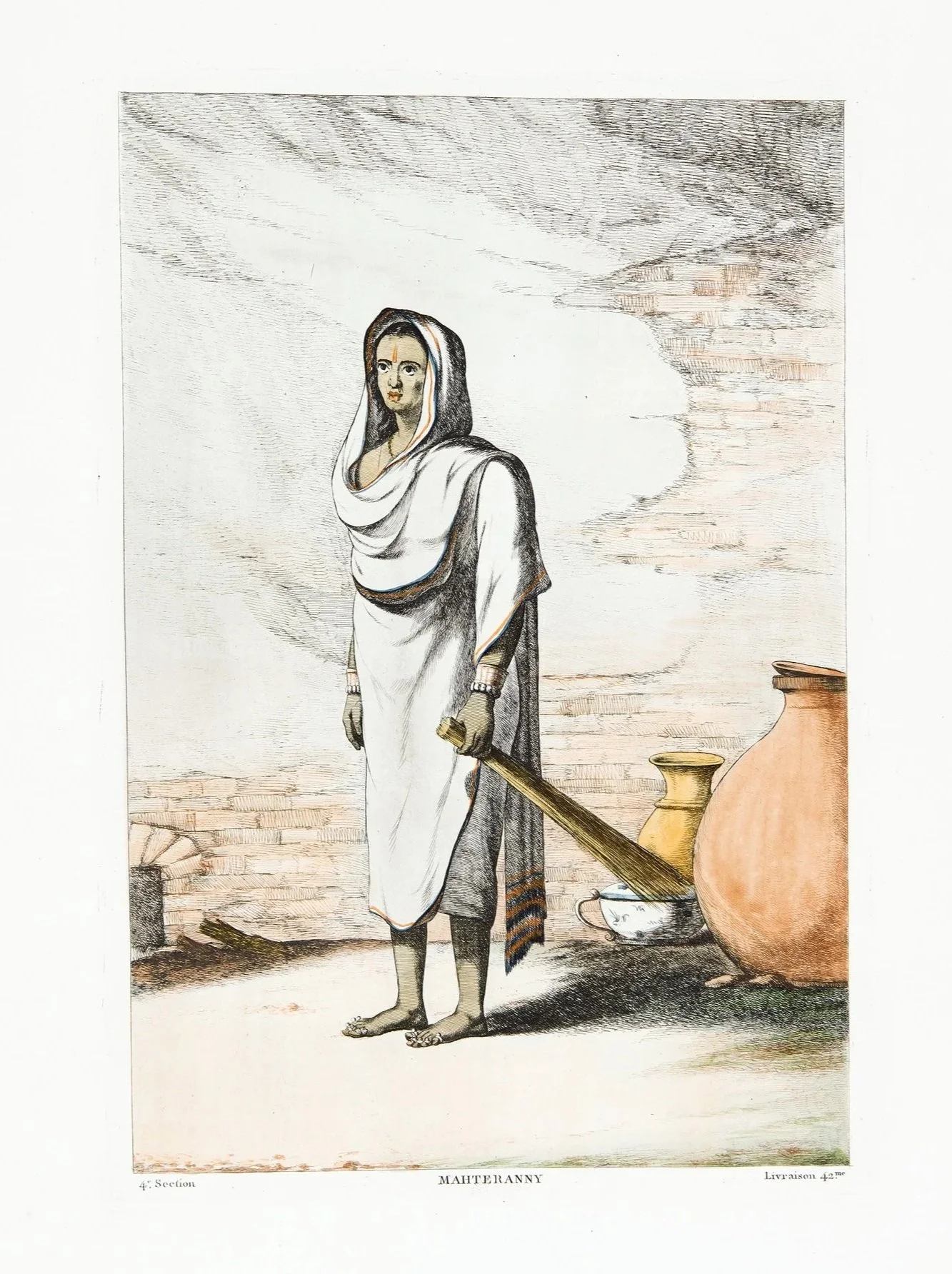

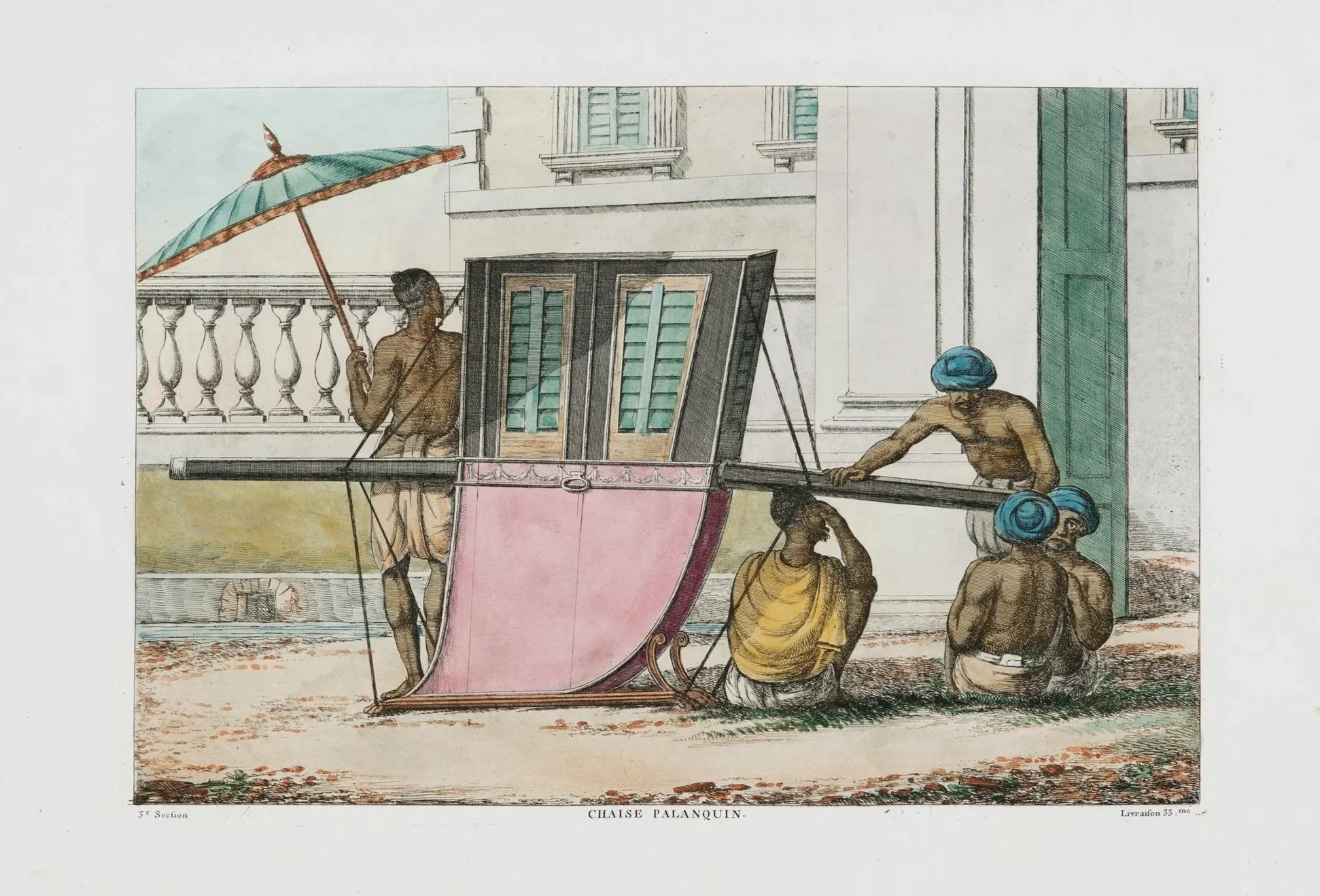

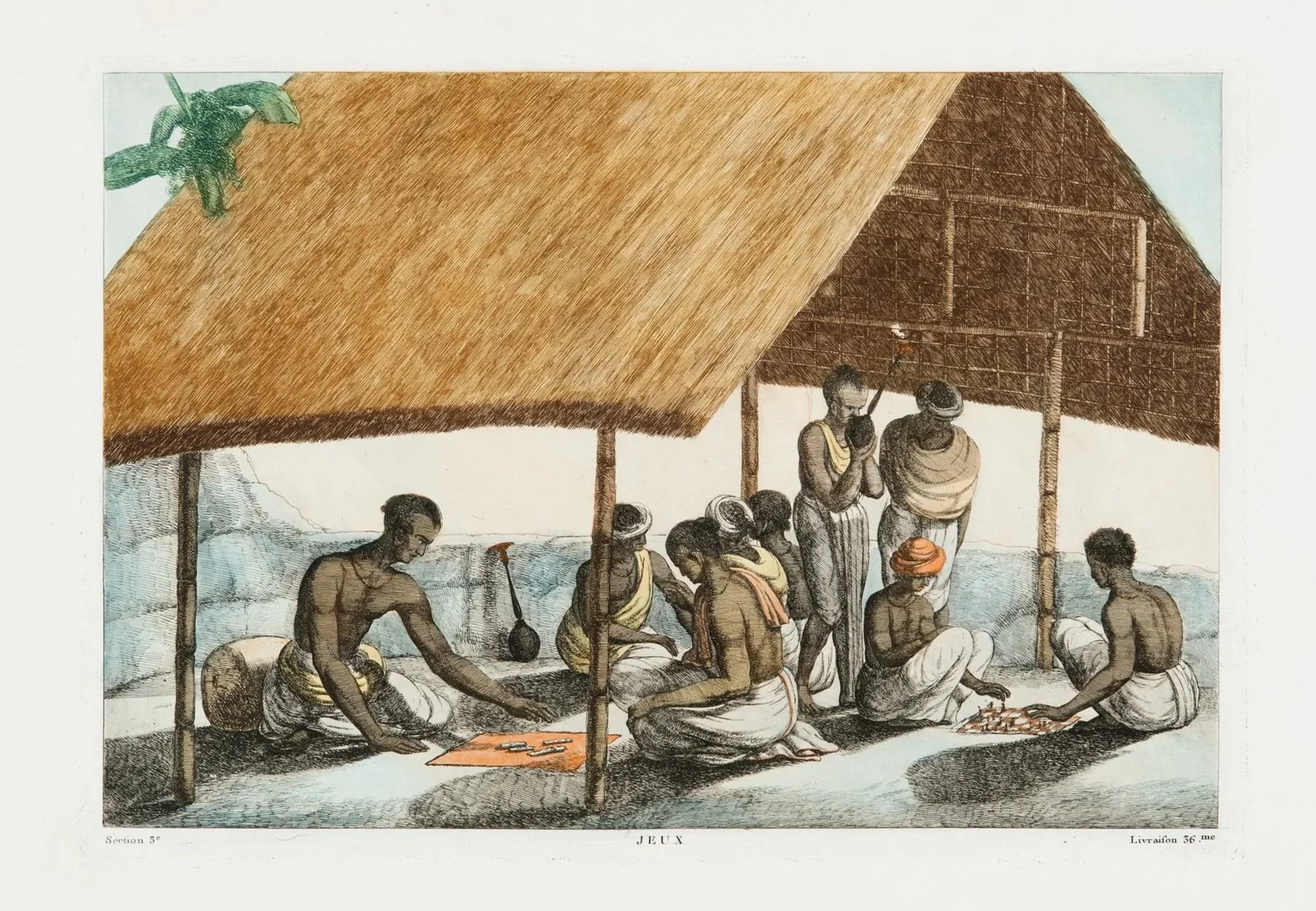

The exhibition showcased 288 hand-coloured etchings from Solvyn’s work, titled Les Hindous (The Hindus), a stunning catalogue of occupations, rituals, and social life that display a caste-based mapping of 18th-century Bengal. Solvyn’s focus was to depict the manners, customs, and dress of the Hindus. However, during his lifetime, his project failed commercially. European patrons were not interested in depictions of ordinary people; they preferred grand portraits of officials, nawabs, and palatial mansions. Yet, two centuries later, his focus on the common people has made his work important to historians and caste-scholars.

Born in Antwerp in 1760, Solvyns arrived in India in 1790 aboard L’Etrusco, a ship engaged in illegal trade that didn’t give importance to the East India Company’s monopoly. Consequently, Solvyns was unable to obtain permission from the board of directors of the Company in London to live in Bengal, which was mandatory at the time. He lived outside the European quarter at several addresses in central Calcutta, around Tank Square. This turned into an opportunity for him as he documented the lives of ordinary people that Europeans seldom saw. Yet, Solvyns could not escape his European gaze. He also received most of his information from Brahmins and was also influenced by the laws of Manu or the Manusmriti. Therefore, his vision of Indian society was seen through the lens of rigid caste hierarchies.

Women in Solvyn’s etchings of festivals appear only in silhouettes, confined behind veiled windows—an artistic reflection of patriarchy. Tillotson notes in The Hindus: Baltazard Solvyns in Bengal that Solvyn’s reliance on the Manusmriti led him to adopt a gendered worldview in his work, where women were described as “incapable of independence.” The women, especially from the upper castes, were kept indoors and unseen. Solvyns claimed: “They are so seldom to be met with in public places... that I have confined myself to the representation only of the men.”

It is in the “Occupations” section that the caste representation becomes most apparent. Solvyns depicted Bengal’s social spectrum—from Brahmins and merchants to potters, cowherds (goyalas), and sweet-makers (moynas). There are also rare portrayals of lower-caste labour, including sanitary cleaners, pig-deliverers (koureh), and even an aghori woman. These figures are invaluable because few other artists of the colonial period recorded them. Yet, Solvyn’s framing—his reliance on the Manusmriti, his facial distinctions (long foreheads, fair skin for upper castes)—show his observations of caste hierarchies. Even the musical instruments he catalogued depicted caste lines: mouth instruments such as the urni were played by the lowered castes while string instruments, such as the tanpura and rudra veena belonged to upper-caste traditions.

Image courtesy: DAG

Although Solvyns died without the recognition he hoped for, his work was later copied and commodified by British printmakers and publishers Edward and William Orme. Edward Orme’s The Costume of Indostan (1807) copied 60 of Solvyn’s Calcutta prints.

In an era when Bengal’s political narrative has downplayed caste, Solvyn’s art reintroduces it as an unavoidable ethnographical fact. His etchings confront viewers with the hierarchical reality of everyday life: the visible labour of the lowered castes and the structured distinctions of occupation.

Tillotson further observes that Solvyn’s prints were also circulated by Indian artists, who sought patronage from European residents. “There is a whole genre of so-called Company painting dedicated to the representation of India’s castes and trades and some of the artists who first fashioned this genre found in Solvyns a ready template,” Tillotson writes. “They copied and skilfully rearranged his figures into new compositions, at times so seamlessly that the connection might escape notice.”

Solvyns not only documented caste but, inadvertently, also helped institutionalise its aesthetic representation. His focus was on documentary representation rather than romanticised scenery influenced by European landscape conventions, setting him apart from his contemporaries such as Thomas and William Daniell. His engravings and etchings—influenced by Flemish realism and print-making traditions of etchings and engravings—are precise, attentive to detail, and possess the clarity of natural history illustrations. The etchings are clearly outlined, focusing on clothing, tools, and posture, and have flat backgrounds, which are illustrated enough to situate his subjects.

Unlike Company School painters of the time, Solvyns did not use rich colours. The colours are often muted, allowing form and classification to take precedence. One might compare Solvyn’s works with another artist Charles D’Olyly as an example of contrasts between artistic styles. D’Olyly’s official duties with the East India Company allowed him to travel and use those experiences as artistic material for his work, which featured market scenes, festivals, and street life. However, while D’Olyly’s works were more narrative and picturesque, Solvyn’s works, in comparison, were typological, aiming to catalogue rather than romanticise and dramatize.

Image courtesy: DAG

Although Solvyns depicted the manners and customs of the people, presenting them in a dignified way, there is a colonial bias in the way caste is depicted as fixed and timeless. An expert on viewing the etchings might admire the meticulous portrayal of his subjects and visual clarity, however, they would also note the unease at the rigid depiction of caste.

In an era when Bengal’s political narrative has downplayed caste, Solvyn’s art reintroduces it as an unavoidable ethnographical fact. His etchings confront viewers with the hierarchical reality of everyday life: the visible labour of the lowered castes and the structured distinctions of occupation.

Image courtesy: DAG

Although his gaze was colonial and flawed, Solvyn’s work allows contemporary audiences to ask: What does it mean for a society to be divided along caste lines and to later pretend that caste doesn’t exist? Solvyns may have failed to find commercial success in his lifetime, but his art endures as it showed both the reality of Bengal’s caste system and the biases of the Europeans that documented it.

***

Sravasti Datta is an independent journalist. She has a Master's in History from Calcutta University and a diploma in broadcast journalism from the Asian College of Journalism, Chennai. Her writings have been published in The Hindu, 30 Stades, Deccan Herald, The News Minute, among other publications. She can be found on Twitter: @sravastid and Instagram: @sravastid_journo.