A roaring commentary on Indian Wildlife

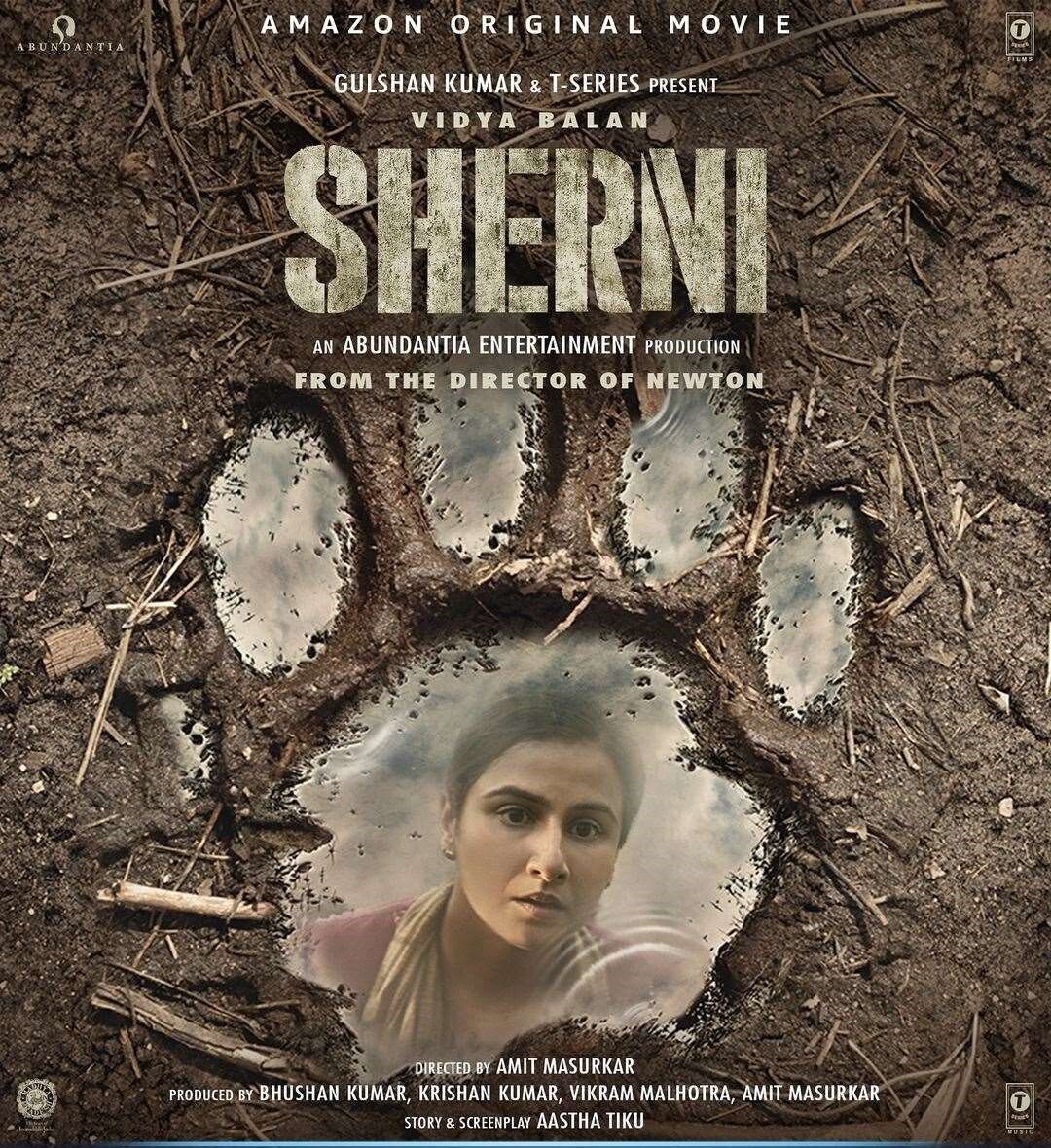

In Amit Masurkar’s man-versus-wild thriller Sherni (2021), a disturbed tigress is on the loose, spreading alarm and fear. But, with critiques of industrialisation, politics, and greed, the film is instead a mirror reflecting the wilder side of humanity itself.

Usually limited to the scope of wildlife documentaries, the man-versus-animal conflict is seldom portrayed in mainstream Hindi cinema. And if it is, the forest is either portrayed as the villain—with the dark, spooky and gloomy vibe—or is romanticised as a sort of foreign ‘other’. In Amit Masurkar’s Sherni, however, the forest comes alive, a realistic place where the habitants appear quiet and peaceful, not as others but friends.

Best known for the award-winning Newton (2017), Masurkar’s latest work is a breather from recent Bollywood releases. There are no chiselled heroes and no actresses doing the hair flip. Although Sherni (released past month on Prime Video) features Vidya Balan in the lead role, it's actually the tigress herself that stands out as the true, barely-seen star.

(The film’s title is a misnomer: ‘sherni’ technically means ‘lioness’; the formal Hindi term for ‘tigress’ would be ‘baghin’).

Balan, meanwhile, is stripped down from her star persona. Her character Vidya Vincent is no saviour; she’s simply a divisional forest officer trying to do her job and make a difference while at it. In a more ‘over the top’ drama, Vincent would have been shouting expletives and have the 'mardaani' as a forest officer trying to prove her point, but in Masurkar’s world, she's strong and confident—without being too ‘extra’.

We learn that a man-eating tigress, T12, is on the loose and Vincent along with her team must find and save her, before more damage is done to the village and its people. Through this narrative, the audience is guided through the forest, witnessing other subplots unfurl on their way.

Sherni is a metaphor for both T12 and Vincent herself. The storyline closely resembles the events surrounding the ‘hunt’ for Avni or T1, a tigress that reportedly killed and ate 13 people between 2016 and 2018 in the forests of Pandharkwada-Ralegaon in Maharashtra’s Yavatmal district. Avni was shot dead by Hyderabad royal and hunter, Nawab Shafat Ali Khan and his son, Asghar, reportedly after she charged them as they were preparing to tranquilise her. Khan seems to be the inspiration for Pintu Bhaiya played by Sharat Saxena in Sherni. He, too, is a hunter, yearning to increase his score of dead tigers and leopards.

There’s now a race of sorts between Vincent’s team and the trophy hunters for who locates the tigress first. In this man-eats-man world, it’s usually the animals who pay the price. Here too, T12 is the one-shot dead to satisfy Pintu Bhaiya’s ego and adds to his number of accolades.

Sherni is also a commentary on industrialisation and how development is pushing the habits of animals’ closer to human settlements, leaving them with nowhere else to go. One scene in particular stands out when Hassan Noorani (played by Vijay Raaz) and Vincent are discussing the tigress’ route and he says that it could have easily gone towards the national park but all ways towards it are blocked with a copper mine on one end, a highway on another, mountains on another side, and some construction work going on somewhere else.

The film also challenges the more urban belief that has villainised wildlife, that blames animals for being in the wrong for coming into ‘our’ cities, for walking on ‘our’ roads. Sherni is a reminder that the converse is true, that it is us—rather than them—eating into their space. Another scene in the film points this out brilliantly during a street play where they show that the animals wouldn’t be harming us if we hadn’t been walking into their territory, in fact. Wouldn’t we attack if an intruder walked into our living room?

Forest politics and bureaucracy roar into the film, rearing their ugly head. Brijendra Kala as Mr Bansal, the head of the forest department, is complacent, and favours certain political parties to get into their good books. This karaoke-singing man is comical, but stands for all the corrupt government officers who fail to do their job due to which the people suffer. It is a reminder of the Ayusmann Khurranna starrer Article 15, which broached similar themes upon its release two years ago.

There’s now a race of sorts between Vincent’s team and the trophy hunters for who locates the tigress first. In this man-eats-man world, it’s usually the animals who pay the price.

While the village and its people are being proactive finding the tigress, Bansal rallies along with the local politicians. In times of crisis, this man is nowhere to be found and sends Vincent instead to face the public’s wrath. In a chase scene in the office, where some people are behind Bansal to catch him and get an answer, he hides in his own forest—a room full with heaps of files, cobwebs and dust. It is a powerful shot and a mesmerising moment, spotlighting the sorry state that many government offices are devoured in.

Local politicians PK and GK try to cash in on the controversy for votes by enraging the public and hiding known facts. Does that sound familiar? It must be. When yet another villager is found dead, a politician blames the opposing party for its inability to stop the tigress’ attacks. The dead man was actually killed by a bear, but he chooses to ignore the facts. The media too, amplifies the situation without having the correct details. The truth and facts are often lost between changing narratives, hungry politicians and media representatives constantly demanding public attention.

The villagers are helpless. When the forest officers ask them to graze their cattle elsewhere and not enter the forest region, they tell them they do not have any other land to take their cattle to. While the government has imposed afforestation schemes, to plant thousands of trees on each district, the teak trees leave no space for crop, which is food for the cattle. An imbalance in our food chain and ecosystem often leads to unforeseen circumstances.

Bollywood has taken memorable trips to the jungle before, in films like Shikar (1968) starring Dharamendra and Asha Parekh, or Jaanwar Aur Insaan (1979) starring Shashi Kapoor and Rakhee. Sherni, however is from a completely different vein, and a different era, made with the purpose to support meaningful cinema and critique our social fabric. It is a roaring commentary on India’s wildlife scene, a call to action, to wake up for some undoing before it’s too late for our entire human race.

***

Nidhi Choksi Dhakan has worked with The Hindustan Times, The Times of India, HT Brunch, and G2. She is a regular contributor at KoolKanya.in. A Mumbaikar by heart, Dhakan shifted to Dubai in 2018. You can find her art on Instagram @sketchbook_stories and her bylines here: https://nc16ultimate.wixsite.com/nidhichoksidhakan