A Sensitive and Essential Partition Story—for Children

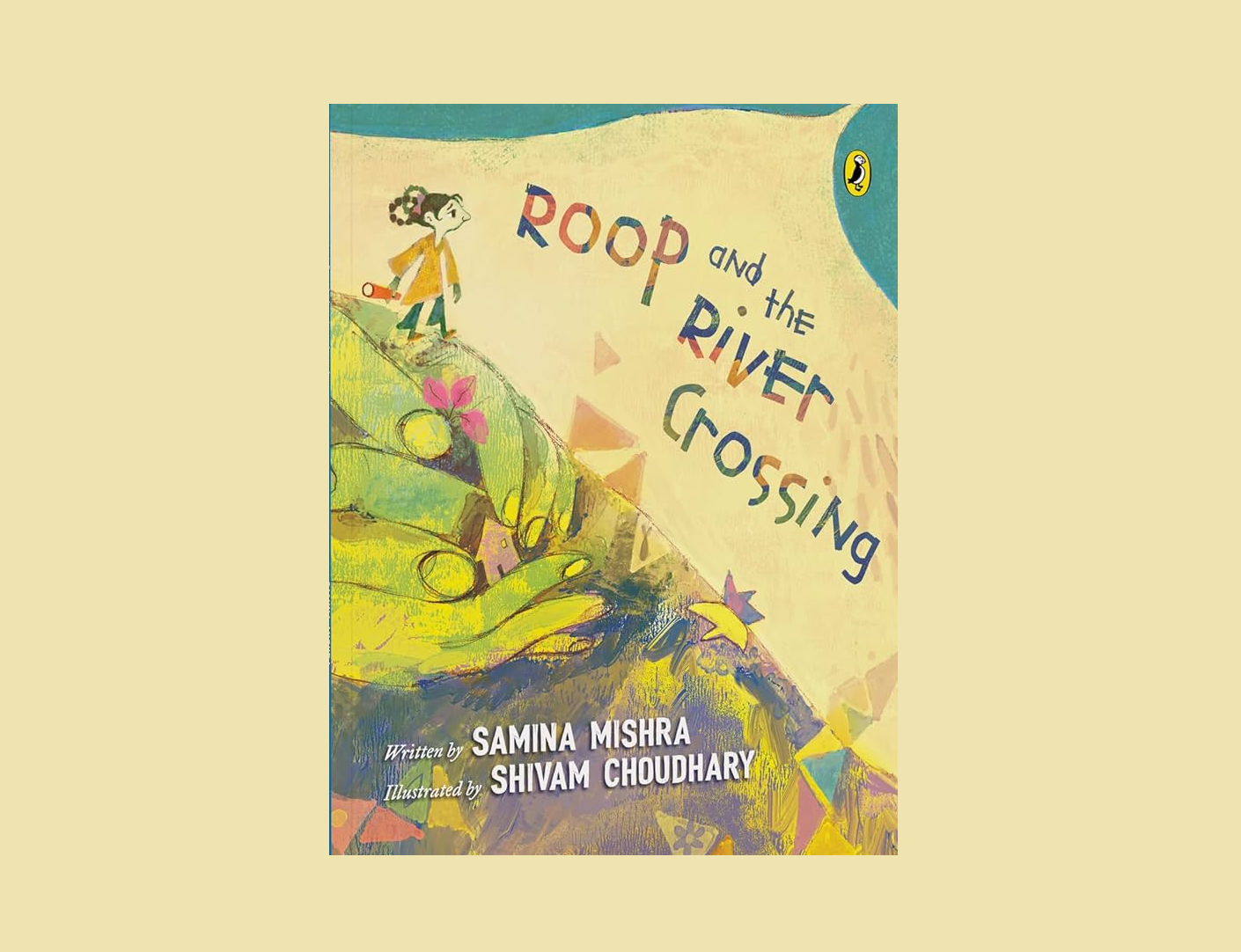

The picture book Roop and the River Crossing (2025)—written by Samina Mishra and illustrated by Shivam Choudhary—gently nudges its readers to reflect upon the ideas of home, belongingness, displacement, and what it means to be uprooted as one steps into the unknown.

In Taika Waititi’s 2019 dark comedy film Jojo Rabbit, a ten-year-old boy growing up in Nazi Germany during the Second World War is recruited to the Jungvolk, a Nazi indoctrination and training camp for young boys and girls. ‘Jojo’ is too timorous and sensitive to be a part of the camp, but he idolizes Adolf Hitler and has the Führer as his imaginary friend. Unbeknownst to him, his mother has given refuge to Elsa, a Jewish teenager, in their attic. Jojo’s anti-Semitic zeal in the face of Elsa’s humanness forces him to confront his supposed ideals. In an article for Business Insider, Jacob Sarkisian strongly advocates for this film to be taught in schools as, “it shows kids how to think for themselves, and to not just assume that what is going on around you is true or right. It teaches kids to educate themselves and to listen to the oppressed rather than the oppressors. Most of all, it teaches kids to be kind, which, in this current climate, cannot be understated.”

The film, set in the first half of the twentieth century, might appear as a problem from a distant past that has little impact on us today, but is the present not equally problematic? Do hatred, intolerance, and prejudice no longer pervade in us? While catastrophes from the past such as the Holocaust and the Partition may not seem politically urgent or even relevant today, its scars still run deep. And our ineptness to understand our past hampers our ability to comprehend our present. Ever wondered what impact such jingoistic nationalism has on children? How, when, and why does their credulity change into hostility, turning them away from humanitarian values?

For children, the habit of reading is important not simply because of the fanciful wings it provides to their imagination, but more so because it teaches them about empathy, about placing themselves in another’s shoes, about being more accepting, and, about not rushing in to pass judgments. Thus, it becomes essential for us to understand traumatic, serious, political events from the perspectives of younger minds.

In the context of South Asia, the Partition of India in 1947 indeed stands as a major moment of deracination. The chaos that surrounds Partition has no doubt been well chronicled in literature as well as in history. The anguish of Sadat Hasan Manto’s deeply troubled protagonist, Bishen Singh, continues to haunt Partition literature. Interestingly however, even a passing glance in the children’s section of a bookstore would reveal only a handful of books on the subject.

For children, the habit of reading teaches them about empathy, about placing themselves in another’s shoes, about being more accepting, and, about not rushing in to pass judgments. Thus, it becomes essential for us to understand traumatic, serious, political events from the perspectives of younger minds.

Samina Mishra’s latest picture book, Roop and the River Crossing (2025, Puffin), illustrated by Shivam Choudhary, addresses this urgent need. “Our map is changing,” says Preet, a friend of the book’s young protagonist, Roop. The inability of adults to give definitive answers about the Partition leaves the children perplexed. Roop thinks to herself: “What had happened to the world?” Though the adults keep reassuring her that things will be “fine,” she is wary of such empty promises and wonders: “Why do grown-ups say that? What is going to be fine? How do they know?”

As the temporal distance between the Partition and the present continues to widen, teaching texts that depict its trauma is becoming increasingly more challenging. With each passing year, attempting to bring alive a tumultuous past that is now almost a century old becomes an uphill task, especially to a generation that is diminishingly acquainted with it.

While writing a picture book for a generation by and large unfamiliar with this catastrophe may have been a daunting task for any other author, Mishra has, fortunately, never been one to shy away from a challenge. In one of her previous books, Nida Finds a Way (Duckbill 2021), she gives Nida—her seven-year-old female protagonist—agency to persuade her Abba to support her in all her endeavours, whether learning to ride a bicycle or sitting with her Dadi at the anti-CAA Protests in Shaheen Bagh. Similarly, in Jamlo Walks (Puffin 2021), Mishra depicts the tragic story of a young migrant girl, Jamlo, who is forced to walk hundreds of miles in the hot summer during Lockdown, while children from affluent families watch television from the comfort of their homes. Poignantly, the author pitches the need for a kinder world where children, irrespective of economic class, are treated with the equality and gentleness they deserve.

Writing Roop and the River Crossing, nevertheless, would have been a formidable task: Partition is a sensitive subject, which requires a delicate approach if its target audience is children. And yet, despite the sensitivity of the subject, it is imperative to make children cognizant of it. Mishra triumphs on all counts.

Choudhary’s illustrations beautifully complement the narrative. The use of earthy colours enhances the overall impact of the book. The pictures are understated but no less moving. The illustrations remain unobtrusive, never diverting the reader away from the story.

Bearing in mind that this is a children’s picture book, the author deftly broaches the barbarity of Partition without getting into its gory details. For instance, hearing slogans of “Naara i takbeer / Allah ho akbar” being raised outside their school, Preet informs her friends, Roop and Noor: “It’s because of Hindustan and Pakistan.” While Noor declares: “I am staying in Pakistan,” Preet states: “Me too...Biji said this is home no matter what name they give it.” When it’s Roop’s turn to respond, she is puzzled: “Isn’t this Hindustan?”

Mishra also hints at the fear and panic that prevailed during those turbulent times when Roop’s school closes early. As the young girls are heading home from school, Roop sees many weary families walking together carrying their meagre belongings with them. She observes: “many among the group...had bandages” and “blood seeping out” of those bandages. This description recalls another picture book on Partition: Nina Sabnani’s Mukand and Riaz (2007), a story based on the real-life friendship between a Muslim boy named Riaz (Ahmed) and a Hindu boy, Sabnani’s father, Mukand (Sabnani). The story is set in Karachi, now in Pakistan. Despite the sobering appearance of a military truck with British soldiers asking boys on the streets to return home, young boys continue to play cricket. Their boyhood revolves around dreams of winning cricket trophies, visiting the local bakery for buns, relishing kulfis and doing service at the local gurdwara. All this changes the day Riaz informs Mukand about the country’s Partition, and urges him to hurry home in order to pack because his family must leave. While Mukand “does not understand what is happening,” he still walks home. Along the way, he “sees strange things—people chasing each other and shouting. He sees blood on the streets.” Though the horrors that people endured during that time were greater and are far widely known, both Mishra and Sabnani tactfully employ subtlety to bring their point home.

In another instance from Roop, the protagonist awakens in the middle of the night to the cries of “Bole so nihal sat sri akal” and “Allah ho akbar” outside her home. She then catches snatches of a conversation between her Papaji and Jaggi Chacha from the next room: “Crossing...Our turn.” Adding to her confusion, she finds her Bebe packing, bundles strewn across the floor. Bebe tells Roop: “We have to leave, right now.” While there appear several questions in Roop’s young mind that leave her baffled, no adult has time to answer her questions. She wonders: “What clothes have you packed? Am I going to miss school? Should I carry my schoolbooks?” The only thing that Roop finally carries with her when leaving home is her favourite toy, the kaleidoscope. They are escorted to the waiting truck in the mohalla by Noor’s Abba and her brother. As people board the truck, Roop hears her Papaji inquiring about Preet’s family. He is told: “Biji is refusing to leave. We will hide them till trouble dies down. Maybe then you too can return.” Mishra does not fail to bring to light that for every refugee who was forced to flee, there were some who refused to abandon their ancestral homes and lands. And that, neighbours who had been living side-by-side for generations, came to their aid and provided shelter.

In the book, Roop’s prized kaleidoscope, brought to her by her Jaggi Chacha from a mela at Sheikhupura, acts as a metaphor foreshadowing Partition. The book begins with Roop peeking through her toy in which “Red-blue-green-purple” comes together in a vibrant jumble of shapes and colours. The rainbow of colours can be indicative of different people living together in relative harmony for centuries. Referring to her beloved kaleidoscope, Roop muses that Jaggi Chacha always brought her the best presents from Sheikhupura. But this year he had brought some news for her Papaji as well. Alluding to the radio statement issued by the British Government on June 3, 1947, regarding the acceptance of India’s Partition by Indian leaders, the author points to the refusal of laypeople to acknowledge the inevitable. A loudspeaker in the bazaar can be heard: “Har har har / Iko kar rab.” Roop’s Papaji tells Jaggi: “Sun, Jaggi...Iko! People here want to be one. No one wants trouble.” To this Jaggi sagely replies: “Praji, if it’s happening there, it will happen this side too. It’s just a matter of time...There was a maulvi in the bazaar at Sheikhupura who had arrived from Agra on one of those trains...He managed to survive only by pretending he was dead...Dehshat, he called it, ‘complete terror’.”

Passing references to Sheikhupura, Amritsar and “batwara” leave the reader in a state of ambiguity. The only aspect that the author is emphatically specific about is that Roop’s family successfully makes it across the river to the other side of the border. Mishra skilfully universalizes the experience and the pain of Partition by not mentioning the particularities of place.

As we gradually inch towards the centenary of our Independence, we must also take a moment to look back at all that has been lost. With the “Red-blue-green-purple” converging to form a kaleidoscopic brilliance akin to fraternity among “Hindu-Muslim-Sikh-Isai,” Roop and the River Crossing sets the right tone to rise above the communal hatred and intolerance of Partition. In today’s increasingly bigoted world, the picture book illustrates goodwill and fellowship towards the ‘other’ in an exemplary manner.

When he brings Roop safely to the other side of the river, she is overcome with gratitude. It seemed as if “Roop and the Pathan were in a slice of the kaleidoscope world, its edges made of scared, confused people.”

In one scene, a tall Pathan stands by the riverside, distributing handfuls of puffed rice and roasted chana to strangers who are being forced to flee. And what could be more heart-wrenching than finding the same Pathan acceding to the terrified Roop’s plea, “You are tall; you carry me across.” When he brings Roop safely to the other side of the river, she is overcome with gratitude. It seemed as if “Roop and the Pathan were in a slice of the kaleidoscope world, its edges made of scared, confused people.” Before he parts, the Pathan blesses Roop: “May Allah be with you, bachcha.” She, in turn, gifts him her kaleidoscope, knowing well that it would now remain in a home far from hers. She realizes that “[s]ometimes, home can be as fragile as the glass inside a kaleidoscope” where everything is “[s]plit up with triangles, split up with circles, split up with lines that splinter the world.”

There is a similar moment in Mukand and Riaz, as Riaz arranges for Mukand and his family to be escorted safely on a ship to Bombay (now, Mumbai). He even brings kurtas and Jinnah caps for them to wear so that they “look like everyone else” and “can leave Karachi without being noticed.” Waiting on the deck of the S.S. Shirala, Mukand tosses his favourite red cricket cap to Riaz, one that Riaz loved and wanted but Mukand would not let him borrow because whenever Mukand wore that cap he felt as if “he can do anything.” They never meet again. But Mukand treasured the Jinnah cap because it always reminded him of Riaz and his childhood in Karachi.

Sadly, all these children—Jojo, Roop, Preet, Noor, Mukand, Riaz—and so many like them had to leave their carefree days of childhood behind and grow up overnight.

The significance of educating children about the Partition, or any other catastrophe that occurred in our past, lies in more than just rote-learning its factually-documented history. Its import rests on nurturing feelings of thoughtfulness and empathy towards ‘the other’ in young minds. Knowledge about the extent of a such tragic events, such as Partition in the case of this book, should be taught to make children understand that pitting one community against another can only lead to havoc as it has previously, achieving little in the way of resolution.

To this end, Roop and the River Crossing is a step in the right direction. It is a picture book that gently nudges a child to reflect upon the ideas of home, belongingness, displacement, and what it means to be uprooted as one steps into the unknown. It raises questions for the child-reader: Who is a refugee? What does being a refugee mean? Can one wrap an entire lifetime into a small bundle, that too at a moment’s notice? And, what does it mean to be a human being? Are we so very different from one another?

Whether Roop and the River Crossing has the makings of a classic might be open to question, but it unequivocally is a keepsake for children’s bookshelves. It brings up for discussion the nightmare that the Partition was, albeit one tailored for young and impressionable minds. In addition, the list of references at the back can help the child-reader explore the subject in greater detail.

Mishra and Choudhary’s book can serve as a point of departure, opening new avenues for discussion on sensitive issues with children. It is up to us, the adults—parents, grandparents, teachers, and librarians—how we make use of it.

***

Navjot Khosla is an Assistant Professor at the Department of English, Punjabi University, Patiala. She has been fortunate enough to have had the best of both worlds – education in India as well as the United States. Navjot has authored a book, A Song of Freedom: Journeying from Slavery to Love in Maya Angelou’s Poetry (2015), paying homage to one of her favourite poets. Her areas of interest include children’s literature, American literature, African American literature, Shakespeare Studies and Indian classical literature. You can find her on Instagram: @1412n_k.