Priya: The Brown-Skinned Supergirl to the Rescue

Ram Devineni-created comic and puppet character Priya is India’s first girl superhero, a feminist icon inspiring a global environmental movement and systematic changes in ecological policies in India.

The teenage girl in salwar-kameez looks right out of a mythological chestnut. She sports a diadem and rides a flying tiger. On the streets of the national capital—where a deadly cocktail of smog and smoke leaves people gasping for breath every year—she is out to implore action on one of the most pressing issues rankling our worlds: pollution and climate change.

It barely matters that Priya—India’s first female and brown-skinned comic superhero—is a fictional character. For the world she belongs to, one fraught with its social ills and stigma, is far from fiction.

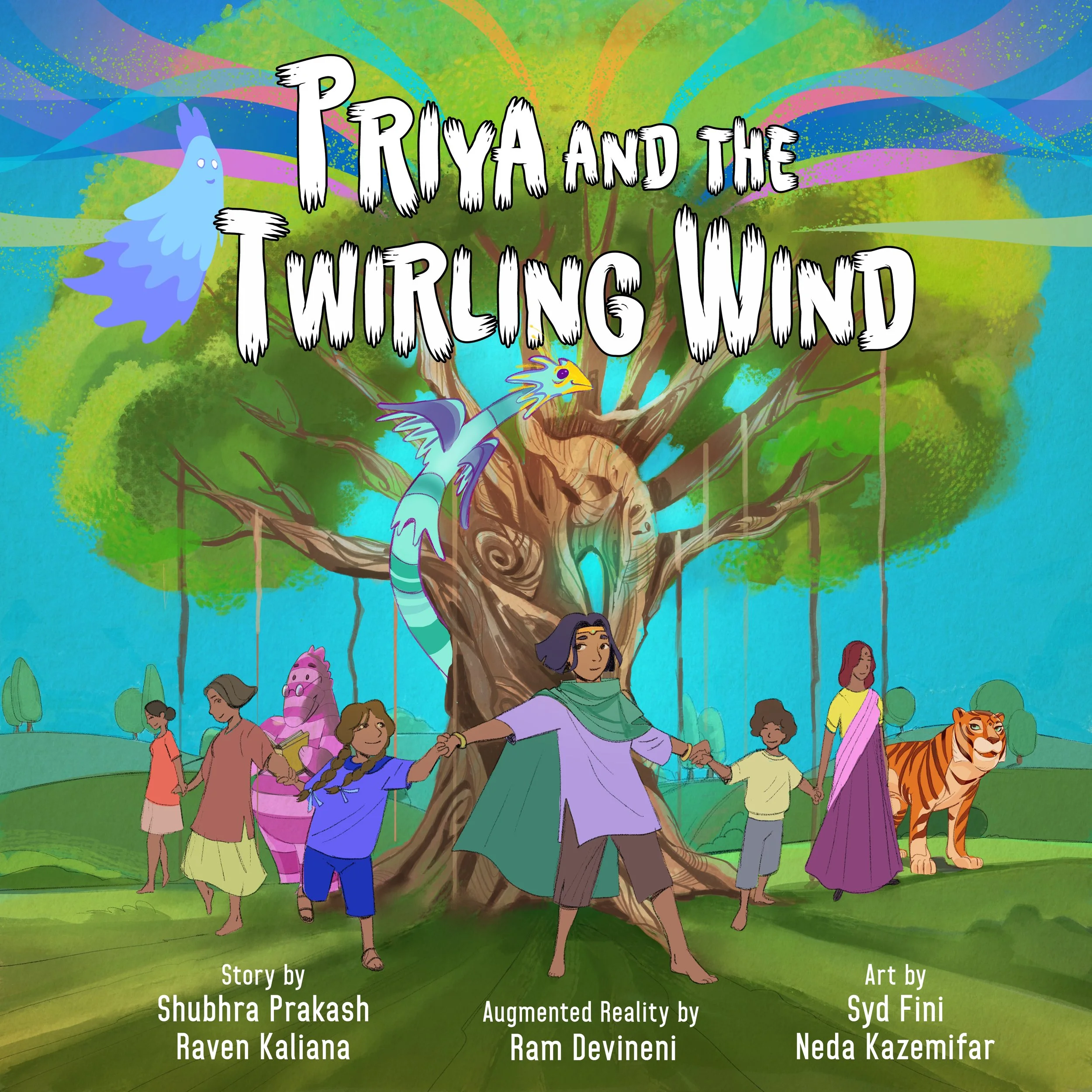

But her superpower is not jumping buildings or shooting spider webs. Priya is perfectly ordinary, except that her magic is breaking the tenacity of social norms and attitudes that perpetuate injustice. In the past, she has made the vocabulary of rape culture and sex trafficking accessible and conceivable to kids and adults alike. She has counteracted forces as old as patriarchy and domination, all with confidence and grace, trying to reckon with them in their full power. In the latest comic, Priya and the Twirling Wind (Rattapallax, 2022), she dons a new hat, of leading the charge by encouraging kids and adults to be more socially conscious towards the environment.

Priya and the Twirling Wind—created by Ram Devineni, Shubhra Prakash and Raven Kaliana—is a meditation on New Delhi’s annual tryst with toxic haze. As pall of smog and gloom engulf the city, Somya, a little girl out for a stroll with her mother, falls sick. She is taken to a hospital, where Priya visits her on the flying tiger, Sahas. They together go to Priya’s enchanted forest—lush with palatial green cover—under threat from industrialists seeking to turn it all into dust.

“Everyone around kept asking when Priya will tackle the toxic haze choking Delhi,” said Devineni, a documentary filmmaker and the force behind all Priya series. “The problem got worse by the year and started taking a health toll on children. It was important that Priya and Sahas approach this from their own experiences,”

Devineni adds that the comic tries to capture the spirit of the iconic Chipko movement. “The struggle presented an ideal opportunity to talk about the effects of climate change and deforestation in India,” says Devineni. “It was also a story of a women-led movement. Chipko was one of the first popular environmental protests in the world led by poor rural women, who saw the effects of environmental degradation on their land and community. Their action inspired a global environmental movement and systematic changes in ecological policies in India.”

He adds that Priya advocates conquering one’s fears to overcome struggles. “I feel one of the biggest hurdles in dealing with climate change is our fear of the sheer enormousness of the problem,” says Devineni. “The Chipko movement teaches us that we can work on local as well as global levels to solve the environmental problems afflicting our families and communities.”

In the most recent instalment, Priya comes to life not only as a two-dimensional comic superhero, but also as a puppet who animatedly engages with climate strike activists Ridhima Pandey (from Uttarakhand) and Alexandria Villaseñor (from the US) in video interviews. Devineni elaborates how it was important for Priya as a puppet to ask questions and inspire other children to do the same. “Both these environmenalists lobbied their respective governments to change their environmental policies. They are at the forefront of the environment movement. Somya represents many Indian children struggling with the disastrous effects of air population in northern India.”

Somya, in the comic book, unifies all women in the nearby village. Together, they hug the trees, preventing them from being cut down. Coming together is a crucial to mitigating the problem, and that is what the comic serves to do, says Devineni.

A rather refreshing part of the endeavour was choosing puppetry, a primitive folk medium, to bolster the cause of this feminist comic. Puppetry may be on the decline as an evocative tool of communication, but renowned puppeteer Raven Kaliana—who brought Somya’s story through life with her magic—is optimistic. “Puppets have historically represented ‘the voice of the people’, in the sense that anyone can create a whole cast of characters from simple materials to tell a story. The accessibility of puppetry means that storytelling can come from people whose perspectives may normally be excluded from the mainstream media. Puppetry can help inspire creativity and a sense of play, which we need in order to imagine better solutions to our collective problems,” she says.

Ram Devineni

Kaliana believes puppets appeal not only to children, but adults too. They have high educational and therapeutic value, and have the potential to bring out the ‘inner child’ in adults.

Puppetry, for Kaliana, has the potential to help our stories connect in a more sensitive manner. She realised she could use puppetry to tell her own story—that of childhood sexual abuse. “I moved created a play and film in the United Kingdom for adults, Hooray for Hollywood, to raise awareness about child trafficking,” says Kaliana. “Puppets helped me show the devastating nature of these crimes from the children’s point of view. Puppets helped humanise the victims, who are usually represented as statistics. After each performance or screening, I'd facilitate a post-show discussion on trafficking. I invited press, politicians, community groups, non-profits; these discussions helped turn back the stigma for victims and survivors of these crimes, thereby inspiring better social advocacy.”

“We intentionally made Priya darker-skinned and associated her with a village because such characters do not exist in popular culture or in comics. Superheroes are over-sexualised and removed from reality. We wanted people to identify with Priya.”

Kaliana and Devineni met at an online conference in 2020 that sought to inform and inspire people who had experienced sexual assault. Kaliana had screened Hooray for Hollywood there and had watched Devineni’s presentation about Priya. “I found Priya so powerful and inspiring, a strong ally who raises awareness about difficult issues that impact women and children,” she says.

While she is rarely branded as such, Priya is a feminist icon. She is a gang-rape survivor (Priya’s Shakti, 2014), teams up with a group of acid-attack survivors to fight a demon (Priya’s Mirror, 2016) and rescues the women of her village, including her sister, from the clutches of sex traffickers in a mythical city called Rahu (Priya and the Lost Girls, 2019). Throughout her evolution, Priya fashions experiences into a potent tool of cultural transformation.

Songachi in Kolkata — the largest red-light district in Asia — inspired Devineni to tell the story of sex traffickers. “Our non-profit partner, Apne Aap Women Worldwide, which has been working with many women and children in that area and had a community centre for them, sent me there,” Devineni says. “There, I met a dozen women who told me their stories. Many of them were coerced or tricked by their family members or were promised domestic work. When they arrived in Kolkata, they realised they were trapped. Some of them knew about the place and consciously chose to work and stay. All women were supporting families in other parts of India. In most cases, the families accepted the ‘uncomfortable symbiosis’ because they had very little money or support. Ironically, the families would not accept their own daughters back because of the shame—but were willing to take their daughters’ money.”

All the women Devineni spoke to, he says, wanted to leave but could not. “Songachi became a psychological and social prison for them.”

Sacrifice, Devineni adds, was the operative word. And this was what prompted him to embed mythology as a critical narrative element in his comic. He tapped into the idea of a volcano and Rahu for the comic. “Often in mythology and ancient cultures, women were thrown into the volcano to appease the gods. The women willingly gave their lives—sacrificed their lives for their community. This led to the idea of Rahu, portrayed as a demon who gets his energy from the volcano and the women who serve him. He is the ‘brothel’ and represents psychological control,” says Devineni.

Priya is a dark-skinned feminist superhero, a novel creation considering the gradual rise of religious fundamentalism across the world in the recent times. Across cultures, women and girls continue to be governed by norms that diminish them. How, in that case, have the comic series been received? “We intentionally made Priya darker-skinned and associated her with a village because such characters do not exist in popular culture or in comics. Superheroes are over-sexualised and removed from reality. We wanted people to identify with Priya. Both Priya and Sahas are universals symbol that can be interpreted in many different cultures,” says Devineni.

He adds that the series have been received well by the masses, and have helped shift gears on how conversations on gender-based violence take place—by switching focus on the survivor/ victim instead of the perpetrator. Several such experiences are beyond the language the world gives us to talk about rape, assault, climate change, etc—for, it truly turns out, the world gives us almost none. Maybe, an innocuous comic can help make a small change.

***

Anshika Ravi has worked as a desk editor with the Indian Express newspaper and science and environment magazine Down to Earth. Her essays and news reports on books, gender, science, and pop culture have also been published in Mint Lounge, Firstpost, News9, Outlook, Arre, and Feminism in India, among others. More of her portfolio can be found here: https://linktr.ee/Anshikaaa. She is on Instagram: @anshikaa.r and Twitter: @anshikaravi.