A Riot in the Guise of Prose

Photo: Karan Madhok

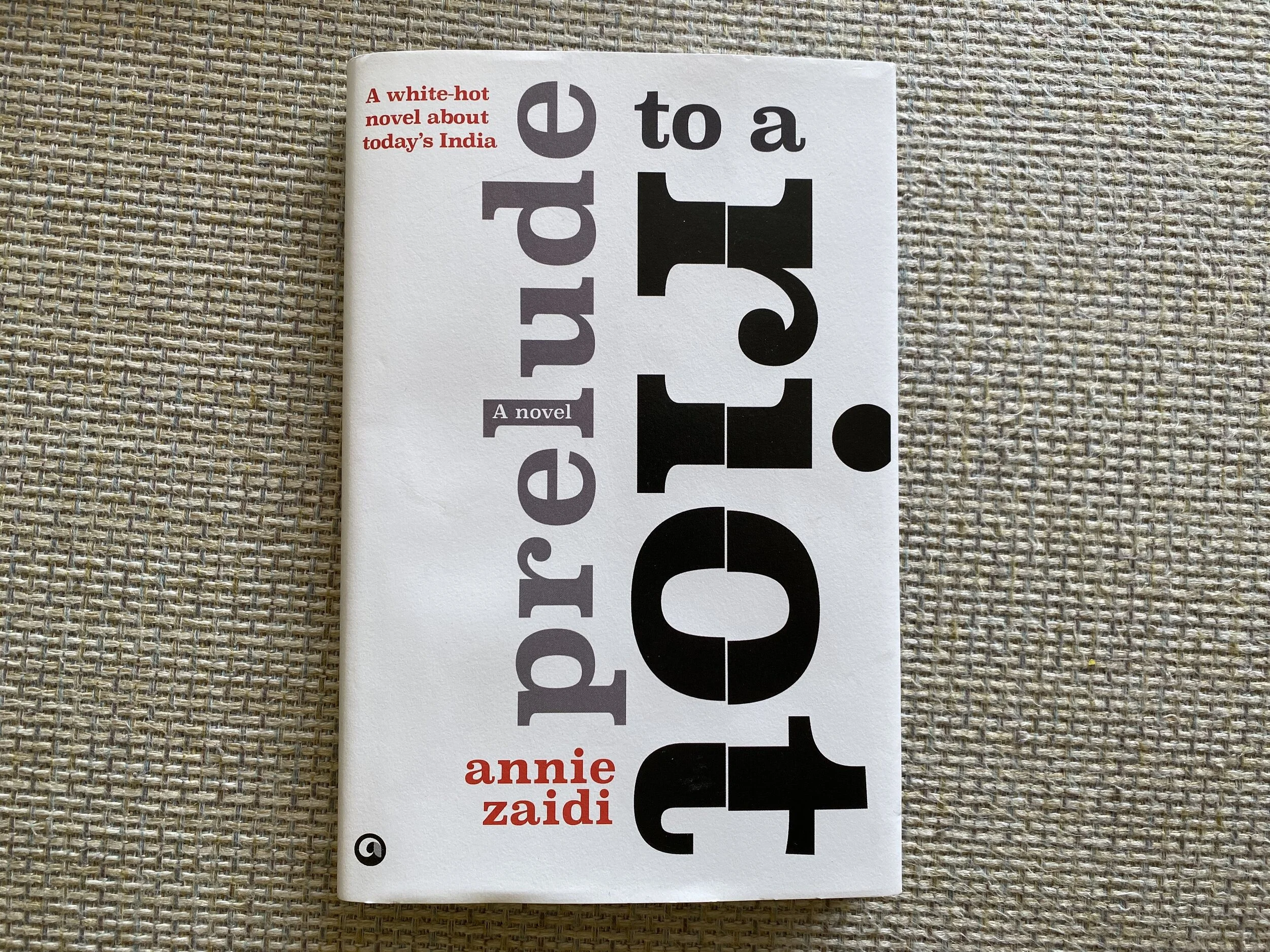

The burden and rot of history lead a small Indian town to the precipice of tragedy. Annie Zaidi’s poetic novel Prelude to a Riot is a red flag of violence to come, a siren sound of the irreversible hate that has been brewed in the town—and the larger nation.

In Annie Zaidi’s tense 2019 novel Prelude to a Riot, a couple of anonymous poets—DeeD and ABC—submit verses to a local publication in a small, quiet Indian town. The poetry is both simple and mysterious, filled with hidden meaning. In a town where the threat of violence looms around the corner, gently polluting the air, tightening the knots between communities that live side by side in uneasy peace, the poems are yet another controversial wrench, so much so that the town’s ‘Self-Respect Forum’ demands an apology and future censure from the publication’s editor.

The editor, however, doesn’t budge, and the poems continue to be printed as usual. Later in the novel, another poem is published under the section-title ‘ABC Writes Scathing Commentary Guised as a Poem’, including the lines:

Laughable, the price of his limbs

Except of course, kidneys and liver and

Skin for man is a harvest festival

Skin him alive and he’s worth the price of his skin

Beneath the rafters of new market establishments, men scurry

As if a man was owed life!

The letters on the left-hand side the acrostic verse go on to spell S P I N E L E S S B A S T A R D S, a small, yet needling form of literary protest against the way certain bodies are discarded, certain souls are crushed, of how human value in the town is chewed and spit out.

As Indians, we become accustomed to this burden of history, inevitably shaded with the past, even when we don’t recognise these burdens on the course of living our lives. But a good novel about India can attempt to condense the complexities; a history lesson of our present day in the guise of fiction.

The short vignette also happens to be a fitting condensation of Zaidi’s novel as a whole. Without explicitly saying so, or without the direct display of violence itself, the novel is red flag of violence to come, a siren sound of the irreversible hate that has been brewed in the town—and the larger nation. Like ABC’s poem, Prelude to a Riot is scathing commentary, guised as prose.

In this unnamed town live three generations of two families, one Hindu, one Muslim, and they happen to be in the forefront of the simmering tensions, tensions that root back to the age-old animosities of ‘us’ and ‘them’, of land-owned and land-coveted, of life-shared and life-taken away. Zaidi’s tale is told through in short, poetic vignettes, through the voices of multiple characters with multiple motivations, stretching the taut narrative almost to breaking point. There are Hindu and Muslim school-children, who witness the growth of communal mistrust among their elders; there are elders that stoke the fire and elders that hope to extinguish it; there is a woman that connects the uneasy waters between caste, class and community. There are voices of others in the town that hope to survive or thrive. There are voices of editors, students, and poets. And there is a heavy-drinking teacher who hopes his final lesson will be to impart some sense of the nation’s history to the next generation, before they, too, succumb to the forces of hate.

One of the challenges of telling an Indian story in English—and often, telling an Indian story that could be easily translatable to foreign readers—is to be able to encapsulate all the complexities of India, our religions and economic distresses, class and caste differences, environmental hazards, political complications, and more, all into one narrative. As Indians, we become accustomed to this burden of history, inevitably shaded with the past, even when we don’t recognise these burdens on the course of living our lives. But a good novel about India can attempt to condense our country’s complexities into a small, analogous narrative. A history lesson of our present day in the guise of fiction.

An example of this occurs early in the book, where Zaidi writes from the perspective of Garuda, a history teacher of Class 10-B: “Do you know how certain kids of rot affect fruit? From the outside, the fruit looks fine. You start eating. You don’t feel the rot until there’s a gravelly bitterness on your tongue. That’s the thing. The white man has left us to rot from the inside out.” Much later, in another soliloquy by Garuda, she writes: “No big colonial sword needs to come down and lash the fabric of the nation. Muscle by muscle, atom by atom, we are being torn from within”.

The ‘history lesson’ can sometimes become overbearing, with Garuda in particular serving as a mouthpiece for the author to set up a background framework—albeit with lyrical prose saturated with metaphor and double-meaning—at the expense of the narrative’s forward motion. Every appearance of the teacher is laden with such passages of exposition, the telling of India’s past complexities. Often, it reads as the voice of the author’s concerns—rather than those of the character.

And yet, Zaidi, in less than two hundred pages, is able to communicate much of this relevant history, and build the characters that populate her narrative. The reader is given just enough information and interiority to learn about their perspectives and motivations to imagine their paths ahead.

This path is a walk on this uneasy tightrope, a balance for livelihood and life. At the centre of the storm are many of the story’s female characters—Devaki, Mariam, Fareeda, and Bavna—who have built the bridge between communities, and can break the bridges, too. Devaki, for instance, has rebelled against family and tradition already, and attempts to balance her ambitions against the view of the town’s rising tensions. Her challenge has been as much to unlearn the shackles of past society as it is to break the shackles for the future.

Appa would say that college was putting dung inside my head. I would say, no, college was taking the dung out of my head. On and on. Me versus him.

Three hundred years’ worth of stories, clogging up the arteries of our men. Sitting tight around their hearts, slimy and thick with half-truths. It makes the dinner table noxious.

And although it isn’t shown explicitly, we feel this noxious air spread from dinner table to dinner table, family to family, all over the town. Devaki’s act of unlearned rebellion seems to be too little, and against the great force of India’s historical anger, far too late.

There is no present violence in the narrative of Prelude to a Riot. The novel’s brilliantly-chosen title, however, is itself the ignition. The title offers a colour palette of rage, the feeling of presenting a flame to a long string of fireworks, promising an explosion ahead. It washes the novel with expectation; so, even when things seem mundane or at peace, we are left tense, in foreboding of the incoming storm.

***

Karan Madhok is a writer, journalist, and editor of The Chakkar, whose fiction, translation, and poetry have appeared in Gargoyle, The Literary Review, The Bombay Review, F(r)iction, and more. He is the founder of the Indian basketball blog Hoopistani and has contributed to NBA India, SLAM Magazine, FirstPost, and more. Karan is currently working on his first novel. Twitter: @karanmadhok1