The Ache of Missed Chances: Ammar Kalia’s A PERSON IS A PRAYER

In his multigenerational saga A Person is a Prayer (2024) Ammar Kalia weaves together several characters, each struggling, yearning, and often failing to find clarity in the shadows of their predecessors. As with many internal struggles, they persist in silence.

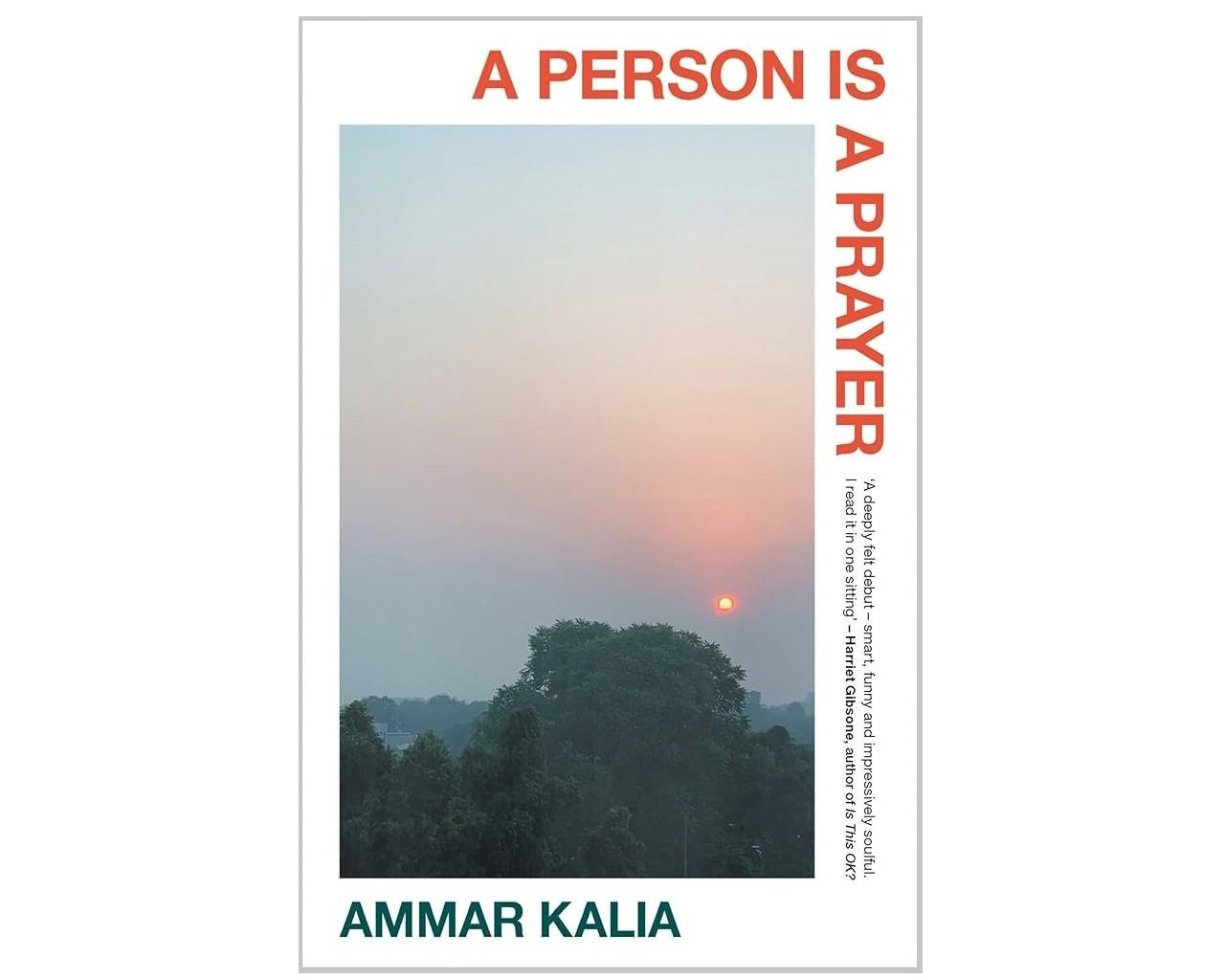

Families carry with them a kind of silence: a silence that pools between shared meals, gathers in long car rides, hums between years of unspoken questions. Sometimes, it’s the quiet of understanding; at other moments, it’s the ache of missed chances. Ammar Kalia’s A Person is a Prayer (Penguin, 2024) captures these aches with tender grace, tracing how it can survive across generations.

At its core, A Person Is a Prayer is the story of family, captured in three days that examine six decades of life. The novel opens in 1955 India, with Bedi visiting Sushma’s house to seek her hand in marriage. Their households are as different as monsoon and drought: Bedi, moulded by a controlling father, struggles to express affection; Sushma, meanwhile, is spirited and radiant, always dreaming of more. Despite faltering conversations, they look forward to starting a life and finding happiness together.

By the time the narrative shifts to 1994, the once bright-eyed couple is now in their fifties, living in England. Their children—Selena, Tara, and Rohan—have grown and built families of their own. Bedi has retreated into himself, accepting life’s mundanity, while Sushma still holds close the dreams she tucked into the margins of her responsibilities, waiting for the right moment.

The novel’s final part, set in 2019, brings the next generation, as Bedi and Sushma’s children, return to India to scatter their father’s ashes in the Ganga River. The children’s voices are now at the forefront, with Selena, Rohan, and Tara each reflecting on their lives and the complicated legacy their parents left behind. Here, Kalia shifts from the third-person narration of the earlier sections to a first-person perspective, allowing the reader to intimately engage with each sibling’s thoughts and emotions.

Throughout this multigenerational saga, the novel weaves together several characters, each struggling, yearning, and often failing to find clarity in the shadows of their predecessors. As with many internal struggles, they persist in silence. Bedi, for example, is a man worn thin by expectations he could never articulate, let alone fulfil. This manifests as an inability to connect with his children, for he never knew how to express love and it casts a haunting void in all three of his children’s lives.

Selena’s reflections on her marriage to John, her complicated relationship with her father, and her growing sense of isolation, form the emotional core of her arc. Seeing her mother as eternally placid and accepting, she set out early to find a path rooted in a strong sense of individual identity. Yet, in breaking away, she finds herself more isolated than liberated. She struggles to reconcile the independence and control she sought with the emotional distance it required. Her father’s emotional absence casts a long shadow over her, and it’s in the moment when she holds his ashes that the reality of their relationship fully hits her:

They were heavier than I had expected and I realised that this was the first time I'd actually held all of him... putting my fingers through every part of this man who I couldn't remember had ever hugged me, or said he loved me. When was the last time he had even laid a reassuring hand on me? (113)

Bedi’s children are repeating the very patterns they swore to escape. One cannot help but feel the bittersweet truth that becoming an adult often means realizing our parents were never the invincible figures we believed them to be, but simply broken humans trying their best.

It’s a moment that collapses memory, longing, and disappointment into one gesture — holding what is left of him. Selena feels the weight of silence and the resentment that festers when love remains unspoken.This was, perhaps, the first time she had held all of him.

Rohan, in ways, is very similar to his father. His habit of retreating inward is burdened by the same need for control and repression. He believes it to be the only defence against the world’s unpredictability. Raised in a household where expectations were felt more than spoken, he carries that legacy with him. And yet, he yearns to break the cycle. His reflections on parenting capture the painful contradiction at the heart of generational change.

The only thing we, as parents, could work towards was to give our kids a sense of freedom to be whoever they wanted to be, to follow their desires, rather than feel the pressure merely to make the decisions they needed to make to survive, as we and our parents had. There were no choices in that past. But some things, like this freedom, are so far from the realm of our imaginations that when they happen, they still seem an impossibility. (193)

The desire to offer what one never received, even while still bearing its imprint. Yet, Rohan’s quiet suffering makes it clear that even as he seeks to give his children a life of greater freedom, he remains trapped by his own internalized insecurities.

Tara, the artist of the family, is perhaps the most inwardly searching of the three siblings. Her reflections are filtered through the shadow of her own secret, the knowledge of her illness she carries in silence for the duration of the trip. She confronts the hollowness that sometimes lingers even when a life appears fulfilled. The act of making art does not shield her from regret, as she recalls the absence of her father’s pride. Her observations about the generational divide, her father’s emotional withdrawal, and her mother’s silent sacrifice, quietly indict the parental figures who—despite their love—failed to bridge the emotional gaps.

I thought about how none of us chooses where we are born or who we are born to. How you can’t always get what you want—in fact, you hardly do—and anything that happens to you has always happened before. We are all just repeating ourselves, trying to be heard, and only some of us cut through the noise. (256)

Bedi’s children are, in their ways, repeating the very patterns they swore to escape. One cannot help but feel the bittersweet truth that becoming an adult often means realizing our parents were never the invincible figures we believed them to be, but simply broken humans trying their best.

While the novel is undeniably rich in its exploration of familial complexities, there is a lingering sense of incompleteness around Sushma’s character. Her presence permeates the narrative through memory, duty, and devotion, but her inner life remains frustratingly elusive. Her sacrifices are evident, her resilience palpable, but her desires are only ever hinted at. This may well be a deliberate narrative choice.

Perhaps this choice reflects how often women like Sushma are reduced to roles rather than afforded inner worlds. Still, it leaves a sense of longing for a deeper understanding of the woman who was the emotional core of the family. The final chapter “Coda” holds a brief glimpse into Sushma’s own thoughts in 1955, waiting to meet Bedi for the first time. It feels like Kalia’s tentative offering to rectify this but one is left wishing for more.

Kalia’s writing is undoubtedly one of the most compelling elements of the book. His lyrical prose, rich with vivid imagery, creates an immersive experience that brings both the external world and the internal lives of his characters into sharp focus. His skill in shifting narrative tone to suit each character’s interiority is particularly notable. The voice of each sibling feels distinct, textured by their emotions and life choices. Kalia doesn’t flatten them into types but allows them to unfold slowly, through thoughts and dialogue.

Haridwar in the novel is not simply a backdrop for a ritual. It holds a mirror up to the dissonance of identity, heritage, and alienation. The city’s descriptions are given tactile attention, filtered through the lens of characters already carrying grief, resentment, and a fraught sense of belonging. It is built through discomfort, through dust and heat and the ceaseless press of people that unsettles more than it welcomes. “We didn’t belong here with our chinos, corduroys and patent leather shoes” (Page 127) Selena notes, as their initial curiosity gives into weariness. The city strips away any easy notion of returning to “roots” they had. “We’re no different from tourists here” (Page 131) she admits, and Tara echoes the sentiment. What was meant to be a moment of cultural reconnection becomes a site of estrangement, especially as they struggle to find the family pundit in a system that appears opaque to them.

Throughout the book, Kalia writes with confidence, trusting readers to find meaning not just in what is said, but in what remains unsaid. His sentences allow tenderness to surface without sentimentality.

By its finale, Kalia’s decision to leave the novel without a neatly tied ending—with grief, regret, and tenderness still swirling unresolved—is both a risk and a triumph. It is a reminder that in family stories, there is rarely real closure. The moments of understanding one another are brief and fleeting, before they quickly slip away once again.

***

Shivani Patel is a writer and book reviewer based in Delhi. She writes about books, memories, and the emotional fine print of being human. Her reviews have appeared in Scroll and Feminism in India. Find her on Instagram @vani_in_wonderland_.