Against The Current

Photo: Karan Madhok

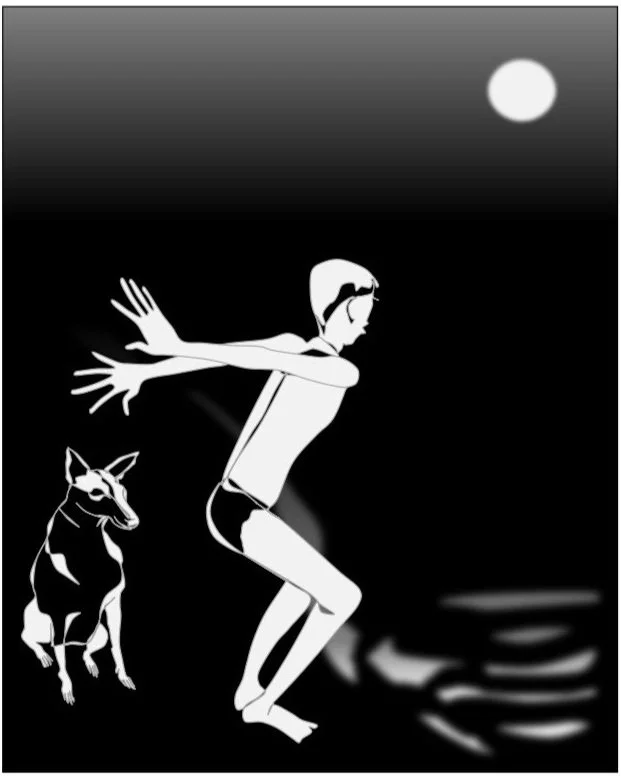

Short Story: ‘But this peculiarly-formed lad is an altogether different animal when he is in water. With his unfamiliar yet uncanny ability, he learns to handle the waves, the deadly undercurrents, the movement of the swells, the whirlpools.’

Here in Varanasi, Mother Ganga flows northward—an ancient river suddenly turning her gaze back toward the Himalayan cradle from which she once descended. Thousands of pilgrims bow low before this rare, north-flowing Ganga, offering their reverence with folded hands and trembling devotion.

It is the full moon of the month of Kartika. Even in early November, the northern winds have already whispered their omen: change approaches. The message can be heard everywhere—in the rustling leaves perched on slender branches, in the grain-heavy heads of ripened paddy, in the dew beading upon the shy, waking grass, in the intoxicating perfume of night-blooming jasmine, in the dry rustle of fallen leaves carpeting the forest path. Several thousand people have gathered near the ancient Adi Keshav Ghat, intent on taking their sacred dip in the holy Ganga at the Brahma Muhurta. All around, the mantras of Lord Vishnu’s worship rise and fall like waves.

Indra Pujari, the priest, is a whirlwind of ritual precision. On this cold night he sits bare-chested, dressed only in a dhoti and a namavali shawl, chanting Vishnu mantras while carefully explaining them to the gathered devotees. His age is hard to guess—perhaps just over forty. His head is mostly bald; his eyes shine with an intense, steady fire. A Vaishnav tilak of fragrant sandalwood graces his forehead, and the sacred thread hangs diagonally from his left shoulder across his torso. His voice, sharp and resonant, cuts through the night air.

On days when the crowd is large, Indra brings his son along. The boy’s name is Katla. Indra brings him, yes, but never lets him approach the sacred fire or the altar. He seats him at a distance instead. The boy’s task is simple yet crucial: observe how many devotees gather, how many choose Indra over the many other priests at the ghat. Competition, after all, is fierce.

Once Katla has assessed the scene, he slips away swiftly to perform his assigned duties. Indra now explains the sacred rules of taking the holy dip during Brahma Muhurta—and why offerings of gold, silver, coins, or ornaments must be made. During Vishnu’s worship, devotees release wealth—gold, silver, coins—into the Ganga as an act of spiritual surrender, seeking blessings of prosperity and divine favour. Not thrown carelessly, but placed reverently inside a copper pot or tied to the bark of a banana tree before being set afloat. It is said the current of Mother Ganga carries these offerings straight to the feet of the Gods.

Indra lifts his voice to its highest pitch and proclaims: “Om Namo Bhagavate Vāsudevāya!”

As the Brahma Muhurta begins, conch shells, cymbals, and drums erupt in a thunderous chorus. The very sky above the Adi Keshav Ghat seems to quiver from the sound.

Indra Pujari steps waist-deep into the icy water, torch held high, and calls out, “Come now, one by one!”

On the days when he is heartbroken, when he can’t arrange food at the temple, when dark clouds envelop the sky and lightning illuminates them—on those days, he misses his mother the most. He recalls being rocked to sleep by her pleasant smell. He recalls she used to feed him rice, applying it on his lips while he slept.

The pilgrims grasp his hand and plunge into the piercing cold, and then, release their offerings of gold and silver, coins and currency, tied to copper pots or banana-bark floats. Indra stands firm, torch blazing against the darkness, a lone guardian of faith and ritual. Every now and then he waves the torch, the flames swaying like a beacon through the predawn mist.

*

Not too far away is the sangam where the Varuna River joins Mother Ganga. A couple of hundred meters away from this ghat, Katla now waits on the riverbank. The boy did have a proper name earlier—Arjun. But no one remembers the name now. From childhood, Katla has been a great swimmer. Born in a riverside slum, his life has always been around the river. He never had to learn swimming; playing in the embrace of the Ganga, he became as proficient as a Katla fish.

He is twelve, perhaps thirteen. A thin, gangling figure. His arms and legs are disproportionately long for his body, which is constructed somewhat like a fish. A big head. Round eyes. A thick lower lip. He tends to gape senselessly. He says very little. His hair is cut close. He has a slightly bent way of walking.

But this peculiarly-formed lad is an altogether different animal when he is in water. With his unfamiliar yet uncanny ability, he learns to handle the waves, the deadly undercurrents, the movement of the swells, the whirlpools. It seems unbelievable to observe how nimbly he controls the chaotic river currents.

His father, Indra Pujari the priest, keeps this hut in the slum as his puja materials godown. He lives elsewhere, leaving Katla by himself in this small shack. Katla’s mother was here for a while. But three years ago, his father married another woman and drove her out. Ever since then, Katla has learned to arrange food for himself from elsewhere.

Indra’s new wife, Duliya, hates to see Katla, and drives him out when she spots him nearby. Katla sits on the Adi Keshav temple platform from dawn until dusk. He observes the pilgrims who visit. He is ashamed to beg. Hunger, however, is a terrible torture. He wraps a rope tightly around his midsection over his trousers, trying to smother the hunger pangs.

Occasionally, his fortune changes. Unbidden, as rain falls from an open sky, someone offers him prasad, donations from the temple. He stands, confused, not sure what to say. He sits in the shade of a tree, eats his fill. The rest, he offers to his dog, Gugli, his faithful companion.

Katla calls her with a sound unlike any other, not quite a call, not quite a whistle, more like half a sigh released through the lips. There is no command in it, no name even: Only familiarity, only belonging. Wherever Gugli may be, she comes running the instant she hears him, her tail wagging

Gugli follows Katla often, like a shadow that refuses to let him be alone. It is as if Katla has been quietly relieved of the right to solitude. In the sunlight, Gugli’s deep brown fur takes on a gentle warmth, and near her forehead there is a small white patch, as though someone once touched her there with a loving finger. Her face is long, her ears perpetually alert, always listening. And her eyes—Gugli feels that they are are unmistakably magical. At first glance, they seem lined with kohl, and if Katla looked at them for too long, something soft tightened inside his chest, almost without warning.

Katla’s birth mother, Bhumi, resides nowadays in the Bengali Tola area, close to Dashashwamedha Ghat. She has married again, set up a new home, and manages to get by doing zari work on sarees in a factory. Bhumi visited Sarai Mohana a year ago. She met Katla, embraced him, gave him sweets, dressed him up, and sat with him for hours. She promised once she got a decent place to stay, she would return for him. She promised to admit him in school. Make him an educated man. Katla did not want to let her leave. He held on to the edge of her sari and said, Father beats me so much, take me along. Bhumi explained to him with great affection and patience, provided him with her address: Raja-Ghat Shiva Temple, Bengali Tola.

On the days Indra thrashes him ruthlessly, when he is heartbroken, when he can’t even arrange food at the temple, when dark clouds envelop the sky and lightning illuminates them—on those days, he misses his mother the most. He recalls being rocked to sleep by her pleasant smell. He recalls she used to feed him rice, applying it on his lips while he slept.

*

On this darkest night of Kartika full moon, Katla is alone at the riverbank. Bare-chested, in half-pants. The buttons are pulled off, so he has wrapped a rope securely around his waist. He is not in good health today. There is a clammy fever and pains in his arms and legs. He spent the day in the hut lying down. But his father instructed him to be at the ghat and then, on the riverbank, from four in the morning. As soon as the light of the torch is seen from a distance, he must go into the water. If he doesn't comply, he will be severely beaten.

So, he stands there on this winter night. His body shakes and his eyesight is occasionally blurred. The ringing of bells and drums reaches his ears. He glances at the torch flame, and descends into the river, until he’s deep down with the water up to his neck. His feet dig into the mud below. The instant he steps into the water, he forgets his fever, his pain.

Mother Ganga welcomes him to her bosom. His strength suddenly comes back to him. The muscles of his arms contract. He flexes his body like a spring, gazing at the waves with keen eyes. The full moon slants in the western horizon. Moonlight glints on the rippling water.

Katla’s eyes scan for any floating object passing by the bank. Standing there for some time, he spies something floating towards him in the faint light. Without delay, he bends his body more and springs like a coiled spring. He swims under for a moment, comes up to take a look, and dives again, swimming across the current to scoop up the object. A minute or so later, he allows the current to sweep him back to shore. He snatches a quick glance at it: A copper pot, its mouth cinched with plastic. He hides it away in a sack and returns to the water to stand guard.

Another leap.

Having struggled for an hour against the current, his body exhausted and weary, he sits for a time on the damp soil of the bank. When the light of the torch is out of sight, he lifts the bag onto his shoulders and back to the slum.

His body shakes and his eyesight is occasionally blurred. The ringing of bells and drums reaches his ears. He glances at the torch flame, and descends into the river, until he’s deep down with the water up to his neck. His feet dig into the mud below. The instant he steps into the water, he forgets his fever, his pain.

The fever is back. Shudders convulse his entire body. He drapes a ripped blanket over himself and lies down. In the fog of fever, as he drifts asleep, Katla sees his mother in the doorway. beckoning him to come with arms outstretched.

He can’t remain in the moment for long. Katla senses someone clutching his hair, jerking him awake, screaming,

—“You son of a bitch, bastard, why are you lying down? Get up. Is this all you brought back? I sent fifteen copper pots and twenty-one plantain stems out! And you brought back only eleven? Where are the rest? Hiding them? Or did you leave them with someone? Or couldn’t you even catch them?”

Indra Pujari pulls him up by the hair, and strikes his back a few times with a piece of wood.

Katla, half-asleep and in a feverish haze, can hardly open his eyes. He only senses waves of pain crashing against his head and back. Not able to sit still, he falls forward onto the floor.

*

Evening creeps in, supplanting the afternoon. Katla is wakened at home by gnawing of hunger and unbearable pain. The door is ajar. Gugli sits there, at the entrance. He rises and begins to walk, without purpose.

Where was he to go? He thinks of his mother. From Sarai Mohana, he walks along the river path in the direction of Dashashwamedha Ghat, to his mother’s address. He has been feverish for days. He hasn’t eaten since morning. Asking directions from passersby, he arrives at Bengali Tola, almost seven kilometers away. Then, the Raja Ghat Shiva Temple. A little ahead, a cluster of few small huts along the riverbank. He goes to every door to ask, but no one knows of Bhumi.

Crushed by despair, Katla sits on the stone platform of a Shiva temple. Finding a quiet corner, he curls himself into a tight coil and lies there. His fever creeps back in again. His hands and feet tremble. His vision blurs. The world melts into a dull, wavering haze.

Illustration: Biswajit Chatterjee

Just then, an old woman passes by, a flower and garland seller near the temple. She asks him why he has been lying here. Katla tells her that he has been searching for his mother. Bhumi, he names her. Sarai Mohana, he adds.

The flower seller asks around, and after a few discussions, returns with an answer. She helps Katla to his feet, and then shows him the way, leaving him outside his mother’s address.

The door of the hut is shut. Katla can hear angry shouting from within. He stands beside the door for some time and knocks a couple of times. But nobody opens.

He hears the screams of a man, the sound of abuses, of objects thrown across the room.

He catches the sound of his mother’s voice, choking with sobs. “She's only a baby. Where can I leave her?”

—“Go to the temple and leave her there. I don’t want a girl child.”

— “She’s a baby. I can’t do it. I’d rather die.”

— “I’ll thrash you and incinerate you at the cremation ghat. I don’t want to see her here tomorrow morning.”

Katla turns and flees, unable to endure his mother’s suffering any longer. His legs can hardly carry him forward. He arrives to the ghat by the riverside and lies down. But sleep doesn’t come. His ears resonate with his mother’s words.

Katla turns and flees, unable to endure his mother’s suffering any longer. His legs can hardly carry him forward. He arrives to the ghat by the riverside and lies down. But sleep doesn’t come. His ears resonate with his mother’s words.

After sometime, Katla pulls himself up and makes a round of the nearby temples. After finding some prasad to eat, he begins to walk back towards Sarai Mohana.

The night is dark. There is no one in sight. Gugli alone sits by the entrance of his hut. Katla, exhausted, despairing, sorrowful, disappointed after the day, hugs Gugli and weeps for a very long time.

Then, draping the blanket over himself, he lies down, with Gugli by his side.

*

Break of dawn. The moon has travelled across the sky, and now sits suspended above the western horizon. Indra Pujari has once again proceeded to Adi Keshav Ghat to conduct the puja. The clanging of morning gongs and bells from the temple waft over the neighbourhood.

By the time Katla rises, the ghat was filled with devotees. The boy wades into the water again, with his gaze glued on the flow and recession of the current. He picks up several floating plantain stems and some copper pots without breaking a sweat.

Now, Katla notices something big bobbing in the distance. In the mid-river. Certainly, someone must have left clothes, gold, silver, provisions—all at once. He springs into the deep water with the fluid ease of a dolphin. He plunges into the water and snatches the object with impeccable precision.

He glances to see a big bamboo basket, covered thoroughly in plastic. Katla is shocked when he peers inside.

Carefully carrying the basket in one hand, his other hand and feet going moving as a unit with the flow with grotesque ability, he steps ashore. Inside the basket, covered in white cloth, an infant kicks its arms and legs. Gugli comes running, encircling Katla with her paws, and barks repeatedly. The baby stirs in the wicker cradle, its tiny fists clutching at air. Katla presses his cheek against the wet cloth, and Gugli wags her tail, as if in solemn welcome.

For the first time in many nights, Katla feels no hunger, no fear—only a weightless warmth, like a forgotten embrace.

***

Biswajit Chatterjee is an engineer-turned-writer whose work blends lyrical storytelling with the textures of memory, myth, and modern life. He has travelled to more than twenty countries over a period of 35 years, drawing on diverse landscapes and cultures to enrich his narratives. Author of a short story collection Tales of the Tidal Times, he writes in both Bengali and English, often moving between the two with ease. You can find him on Instagram: @biswajitchatterjee1964.