‘I have exiled my heart; I loved across boundaries’—An excerpt from Arshi Javaid’s YAADGAH: MEMORIES OF SRINAGAR

‘However, the happiness was short lived. Soon there was a knock on the door and all hope of love was lost for them. Ayush’s family had informed the police that their son had gone missing for a few hours, and they suspected he had been kidnapped by militants.’

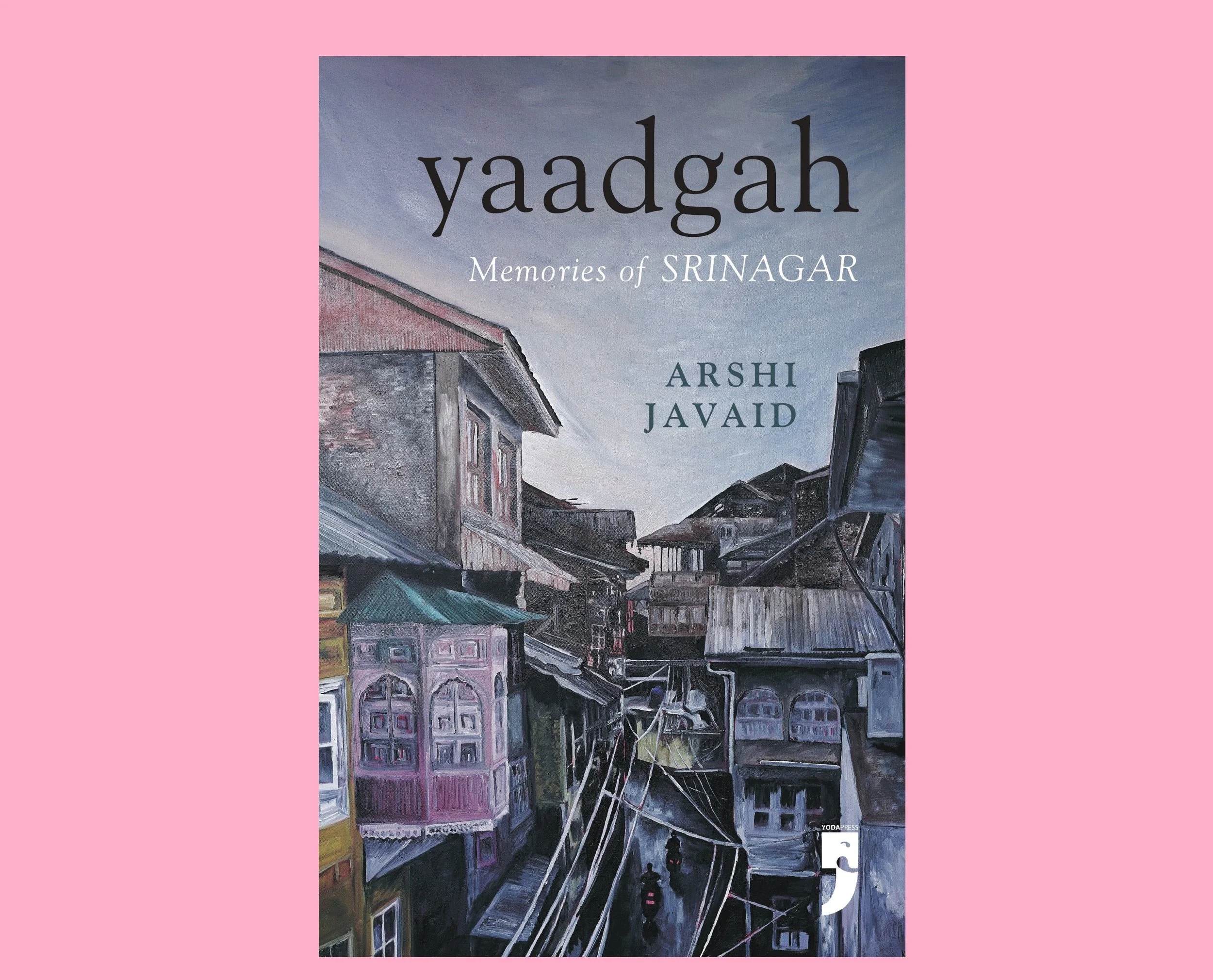

Yaadgah: Memories of Srinagar (Yoda Press, 2025), is a collection of 10 essays dedicated to the old city of Srinagar. Against a backdrop of active violence and conflict, editor Arshi Javaid aims to capture the city’s transitional urban geography and demography, the gendered urban landscape, and its multicultural neighbourhoods. Thematically divided into four sections—Those Who Never Left, Seeking Home, Yaarbal (Meeting Point) and Shelters of Solace— this anthology seeks to establish an archive of collective memory, personal narratives, and stories of nostalgia, loss, and grief within the old city. Interspersed with the text is the astounding visual imagery of the city, which aims to capture its beauty, resilience, and its histories at every corner.

This excerpt, written by Javaid, is titled, “I have exiled my heart; I love across boundaries”.

In the twilight hours of a rainy March evening in 2022, a security alert chimed on the computers of the police and surveillance grid in Kashmir. It was an SOS call that needed to be addressed quickly. Allegedly, a 17-year-old boy from the Kashmiri Pandit community had been kidnapped by militants. He had left home for school, but did not return at the scheduled hour.

After the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019, there was a new wave of targeted killings of Kashmiri Pandits by unknown gunmen. In Kashmir, unknown gunmen are a shadowy phenomenon. With such a thick ratio of armed personnel vis-à-vis civilians, unknown gunmen appear and kill people like wanton boys kill flies. And in the world’s largest security zone, none of the unknown gunmen could ever be traced.

The boy in the picture had left home for tuition in the morning, but did not return at the scheduled hour. The family called the school to know the boy’s whereabouts, only to find that he had never reached school that day; his friends were called but nobody knew where the boy was. Where could a 17-year-old have gone, if not kidnapped or taken hostage by militants? Soon the news spread widely and was carried by news portals. Within no time, a hashtag campaign was started by the Pandit community outside Kashmir. The community members in Kashmir expressed fear and resentment at not being provided ample security by the state.

In Kashmir, unknown gunmen are a shadowy phenomenon. With such a thick ratio of armed personnel vis-à-vis civilians, unknown gunmen appear and kill people like wanton boys kill flies. And in the world’s largest security zone, none of the unknown gunmen could ever be traced.

*

The next morning the IG police addressed a press conference congratulating his team and the IT cell for rescuing the boy within no time. He also revealed that the case was not related. However, very soon, the favourable hashtags began peddling hate against the boy in the picture. “Punish the boy” and “Shame on you” were some keywords.

*

Sometime in November of the same year, Ragini walked me to the house of Ayush, the boy who was allegedly kidnapped. We entered a newly constructed house where the boy’s mother was mopping the floor. With her frail structure, she was rearranging the shoes on the front balcony, putting them in a queue like disciplined students. One look at us and she tells Ragini that everything in the house needs to be sorted and systemised regularly, each and everything requires her careful attention. We offered to visit later, but she directed us to a room where she would join us after she finished the chores. Meanwhile, her sister-in-law, drenched, arrives to tell her she is cleaning the washrooms of the house. She says to us before heading out to clean again: “Our children make this space a garbage house. We find it hard to tidy and reorganize everything.”

Razdan worked very hard to construct this house after they brought down the worn-out structure they inherited from their father. The new house consisted of several rooms overcome by objects, wearing its own viscera on the outside: utensils, tape recorders, a DVD player, an LED television, computer monitor, and other gadgets were scattered around the house. The family did not think of migrating out in the 1990s because their ailing old mother wanted to live her last years in Kashmir. The Razdan brothers also envisioned a certain financial prosperity in staying back.

They had jobs and were skilful too, so they could get private assignments after work hours. A migrated life would not have been as useful, Razdan would often tell their children.

We enter a room and find Ayush sitting there. He seems to be distant from the cleaning choir. With his symmetrical chiselled features, wide forehead, and well-groomed clean skin, Ayush bears a striking resemblance to Asim Azhar, a Pakistani singer and actor. As he introduces himself and his educational journey, a certain innocence radiates from his eyes. He whispers about the need to be focused on his goals and how important it is to make up for lost time as he has just returned from the Juvenile Home. Another stark realization he shares is to listen to parents and prioritize them over everyone else. He asks Ragini if he can confide in me and share his story. Apparently, Ragini, my interlocuter, had taken a hard-line position against the community when tough times fell on Ayush.

In 2016, Ayush met a girl on Instagram. Weeks and weeks of talking converged into a secret love affair. Passions ran high with each passing day, but it was difficult for the two to meet in person as Srinagar rarely opened in the first months of their courtship. They had begun talking after the commander Burhan Wani was martyred, and for months, a curfew was imposed in Kashmir. When things began to normalize, they decided to meet, but their backgrounds were too contentious to meet in public. After all, everyone in the mohalla knew Ayush was from one of the few remaining Kashmiri Pandit families and Rosheeba had a Muslim background. If spotted together they could arouse unnecessary attention. So, the two decided to delay the meeting as long as possible, but Ayush ensured he walked around Rosheeba’s house each day to catch a glimpse of her or wait at the bus stop which Rosheeba passed through. The love blossomed through shared horoscopes, food recipes, favourite songs and inspiring quotations on Instagram. As it became difficult to stay apart, the two decided they should perhaps meet in the Civil Lines area where nobody knew them. The two started meeting frequently in cafes in the Civil Lines area, defying the familiar gaze while becoming part of the invisible matrix of the outer part of the city.

As the relationship went along, both were clear that they would elope as soon as they were legally adults. There was no future for them other than eloping, as the families and communities would not have accepted the relationship under any circumstances. But the plot did not move as expected. Someone from Rosheeba’s extended family spotted her with Ayush in Civil Lines. They had suddenly become visible through invisibility. To make things worse, the identifier knew Ayush by face and family name for he had seen him strolling in the mohalla. The news reached both families and there was an uproar. Rosheeba was locked in, her phone was snatched by the family, and she was not allowed to meet anyone.

As the relationship went along, both were clear that they would elope as soon as they were legally adults. There was no future for them other than eloping, as the families and communities would not have accepted the relationship under any circumstances.

Days and days passed without any news of her. Ayush was consumed and devastated when a new idea struck him: to fake a break-up so Rosheeba’s movement out of the house would be restored, and to elope as soon as things moved to normalcy. They could not wait to become adults legally; the circumstances had changed for them suddenly. Soon a break-up was faked and a cooling period of a few months was put in place so that Rosheeba’s family would stop monitoring her. As soon as their grip loosened, the two decided to pretend to leave for school and fly to New Delhi. Ayush had kept logistics ready: he had saved some money over the years, stolen a piece of his mother’s jewellery which he pawned to buy the flight tickets and to pay for other expenses.

The plan was to reach Delhi and get married as soon as possible. The second step was to find a job in a call centre which hired people based on matriculation. It started snowing the morning they were supposed to take the flight. Ayush joked to Rosheeba that when Shiva and Parvati got married, it snowed, so this was a good omen. However, it turned out to be not so good an omen; all the outbound and inbound flights from the Srinagar airport were cancelled that day. In Kashmir, life comes to a standstill with the slightest weather changes. The two decided to take the first flight the next morning and took refuge in a nearby hotel. With their mobile phones off, they had disconnected from the madness of the practical world, to slip into a surreal corner. Tears trickle from Ayush’s eyes as he vents the memory of the moment. “Whenever we held hands before we were scared to be spotted by relatives and acquaintances. This was the first time we held hands without any fear. It felt like our skin was sinning and liberating itself of the baggage too.”

They were anguished that the flight did not take off but were hopeful that by the next morning, they would be away from there to a place where their religious differences would evaporate. They waited for the night to pass. However, the happiness was short lived. Soon there was a knock on the door and all hope of love was lost for them. Ayush’s family had informed the police that their son had gone missing for a few hours, and they suspected he had been kidnapped by militants. A high alert was initiated and a community vigil was launched through a virtual medium. So that the office of the Home Minister for the Indian State got involved and directed that the case should be taken up on a priority basis. Ayush and Rosheeba were located the same night and by midnight, they were under police custody. Both were taken to a magistrate where Rosheeba cried out loudly that she loved Ayush and the day she becomes an adult, she would marry him under the Special Marriage Act. She also disclosed that she had eloped consensually and was not kidnapped by him.

While Rosheeba was taken by her family, troubles weren’t over for Ayush. Ayush’s family was worried that the Muslim community might come out against him. However, something else happened, the Pandit community wanted to punish Ayush for trespassing. He had brought shame and dishonour to the community. The family was cast out. His parents feared that if Ayush was taken home, he might be attacked by the remaining Pandit community. They appealed to the judge to lodge Ayush in a juvenile centre till the community rage abated. A meeting was organised in the nearby temple complex to teach a lesson to erring youngsters like Ayush. The family had to discontinue their visits to the temple for the scorn they met there.

Everything came crashing down and both of them became strangers to one another. The love was crystallized in religion, from an infidel’s love to a transgressor’s love. I look at Ayush, whose eyes have widened by now. “It’s perfect emptiness, the ideal vacuum, but some day my community will have to answer as to why they boycotted me and my family. There have been rare instances where people were involved in cross-religious relationships, but maybe some of them are braver than us. Age and class are on their side.”

He ends the conversation saying, “I have exiled my heart, for I loved across boundaries.”

***

Dr Arshi Javaid is an Einstein Junior Scholar at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Her previous work includes Kashmiri Nationalism, 1989–2016: Contested Politics of ‘Self’ and ‘Other’, published by Transcript Verlag in 2024. In addition to her work on nationalism, Arshi is deeply engaged with urban spaces’ socio-political and cultural dynamics. Her research explores how spatial politics shape political identities, particularly in conflict zones like Kashmir. You can find her on Instagram: @arshijavid.