To Live in a Language: An interview with Sumana Roy

Photo courtesy: Sumana Roy

Poet, writer, and essayist Sumana Roy speaks to Ronald Tuhin D’Rozario about the creative process, shifting between poetry and prose, and the ‘joyous riyaz’ of a literary life.

Sumana Roy is a poet, writer, essayist, and editor. She writes from Siliguri, a sub-Himalayan town in Bengal, but often switches places with Sonipat, Haryana, where she works as an associate professor of English and Creative Writing at Ashoka University. She is also working on the Indian Plant Humanities project with the Centre for Climate Change and Sustainability, at Ashoka University.

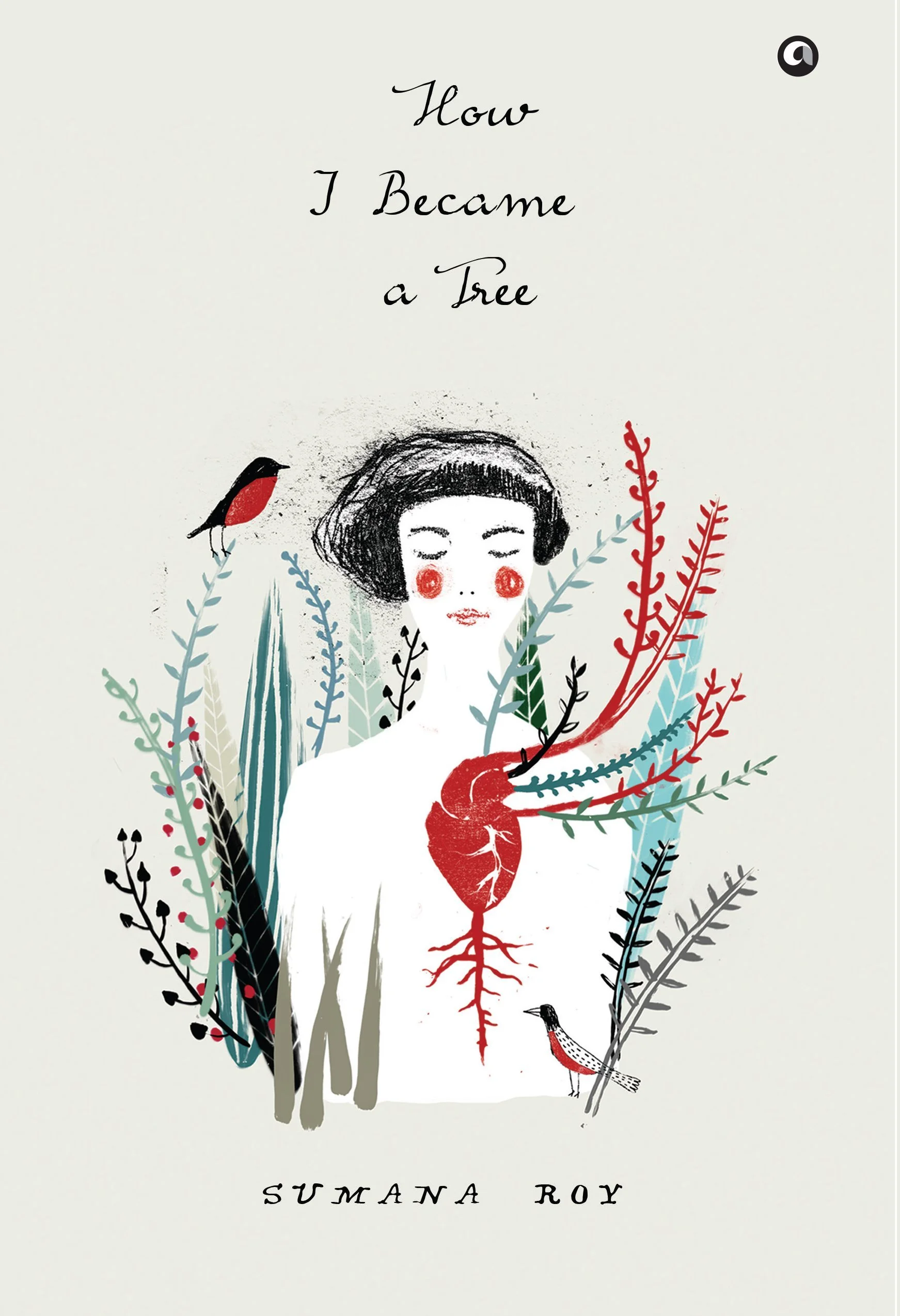

Roy is the author of several published texts, including How I Became a Tree (2017), Missing (2018), My Mother’s Lover and Other Stories (2019), and two poetry collections, Out of Syllabus (2019) and VIP: Very Important Plant (2022). She has edited with an introduction Animalia Indica: The Finest Animal Stories in Modern Indian Literature (2019) and has co-authored Among The Trees – A Field Trip (2021). She is also the co-editor of On Eating, a multilingual journal of food and eating.

Roy was a Carson Fellow at the Rachel Carson Centre for Environment and Society in Munich (2018), and a Full Time Visiting Fellow at the South Asia Program, at Cornell University (Fall 2018). She has been awarded the Omega Resilience Awards fellowship for her outstanding contributions to the field of plant humanities.

Currently, Roy is working on a book project about plant thinkers in twentieth-century Bengal, forthcoming for Oxford University Press.

In an in-depth interview, Roy spoke to about the creative process, shifting between poetry and prose, and the ‘joyous riyaz’ of a literary life.

The Chakkar: Thank you for giving me your time, Sumana. Let me begin by asking how you developed this strong connection with botanical life, and what made you write your first book, How I Became a Tree?

“Everything is a draft: a poem in our laptop, a singer trying to coax their voice, a cook trying to get a flavour right. We might meet it at various stages in process, the poem and the song and the food getting ready to meet the world.”

Roy: I have no sense of this ‘strong connection with botanical life’, Ronald, just as I have no sense of loving those I do. It is what others, sensing what must have seemed to them to be an uncommon affection, have ascribed to me. I pay attention to everyone and everything I care for. The plant world is one of the many living forms I feel close to.

The Chakkar: In How I Became a Tree, you have mentioned “tree time” and your search for its existence. How would you like to investigate the fact that trees have always been a part of our intimate spaces, though in a more processed form—be it a wooden bed, a wooden almirah or a bookcase?

Roy: Plant life has a rich afterlife in a way other living forms don’t. They are alive even though they can no longer produce their own food. Intimacy is subjective: we walk on the earth but may not feel that intimacy just as a librarian might not feel the kind of intimacy you mention with bookshelves. What can be more intimate than kneading flour into a dough? That, too, owes to our relationship with plants, but also our own selves.

The Chakkar: Your mother tongue is Bangla but you chose to write in English. While you allow the intimacy of thoughts to be expressed in a foreign/adopted language, do you feel an internal conflict between two languages about who ‘owns’ you more?

Roy: Not at all. I think we are well past the stage where we have to prove that English is not a foreign language, that it is as Indian as any of the languages we speak or live in. All language is intimate if you think of where it comes from and where it can reach. The choice to write in English was because of the circumstances of my schooling, a decision made by my parents. It allowed me to think in the language and live in it.

I love Bangla: hardly a day goes by when I do not think to myself about how fortunate I am to have been born into a language that is so deep and playful and poetic. I like the Nepali language, particularly its expressive register, very much as well. But I can create only in English.

The Chakkar: How important do you think the role of language in a modern world when many prefer to use abbreviations or shorthand of speech?

Roy: We live in language. If a certain group of people feel the need to use abbreviations, they must have their reasons. I don’t feel annoyed or distracted by abbreviations that I don’t understand. Who knows, someone might write a novel in this language some day? I might not be their target reader, but that wouldn’t bother anyone.

The Chakkar: India has produced multiple fine poets across the generations, and poetry has always been one of India's mainstream practices of art. Yet, what makes it so challenging to establish oneself as a poet, or earn a good publishing brand deal as a beginner?

Roy: I wouldn’t know how to answer this; I have neither established myself as a poet nor have I earned a good publishing deal as a poet. I also think that these are not the reasons one comes to poetry. A poet doesn’t need the attention of a stadium. Kabir or Mirabai, were they alive today, wouldn’t have got great book deals, even though we know many of their poems by heart now. I understand that poetry is a business, but I haven’t tried to understand it as a business yet. That part doesn’t interest me. I have three unpublished collections of poems in my laptop. If they find a publisher someday, I would be happy. If they don’t, I wouldn’t be sad. They have brought me great joy: creating brings delight of the kind that publishing doesn’t. The latter is too other-directed and connected with routes of power.

The Chakkar: Often, you have mentioned the ‘riyaz’ (training or practice) of writing. The modern writing scene has evolved with time and has produced some fine writers like yourself, but don't you feel that there seems some rush around in getting the works published more than the slowness of practicing and perfecting the art?

Roy: A published poem—a poem that got lucky—is also part of the same cycle of riyaz like a public concert is riyaz. Everything is a draft: a poem in our laptop, a singer trying to coax their voice, a cook trying to get a flavour right. We might meet it at various stages in process, the poem and the song and the food getting ready to meet the world, but there is always an afterthought: we edit our work even after it has been published, the reason it is so hard to read from one’s published book, because we want to change a word or phrase even though it’s now inside a book; or why a singer feels frustrated for not having got a particular note or phrase the way they would have liked to; or how a cook says that garnishing it with something else might have enhanced the flavour. To recognize the riyaz to be as joyous as its public outing is freeing. At least for someone like me.

These are not simple binaries, the ‘rush’ of publishing versus the ‘slowness’ of practice, though they may seem so. One shouldn’t be shamed for their desire to publish just as one needn’t be praised for their desire to keep their work to themselves.

The Chakkar: Your first full-length novel Missing revolves around the protagonist Kobita’s life, and it has left an indelible mark in readers’ hearts, just like How I Became a Tree. How different is the art of writing fiction from non-fiction, as they both carry some form of research and narration. Which form of writing do you feel more connected with?

“Every single word we use is a commitment on our part to that history and to this moment of our aligning our history with that tradition. I test each word for how my body, particularly how my mouth, responds to it. It is my first index of the honesty of experience.”

Roy: To answer your second question first, my favourite forms are the poem and the essay, shorter forms, the minor forms today. I go to the poem to experience the thrill of language being made new in every poem; I go to the essay to experience its elasticity, its accommodativeness as a form, its freedom.

It would be impossible to explain the difference between fiction and nonfiction in an interview such as this one. It is, as you know, not the difference between invention and ‘truth’. What is the voice that is speaking to us? Does the subject I want to write about need a poem or an essay or a story? These are urgent questions, and their need and immediacy determine which genre we choose.

The Chakkar: Your collection My Mother's Lover and Other Stories carries fourteen tales of people suffering from curious ailments. Here, you have compared writing, which is a sort of therapeutic exercise to the writer, to an ailment as viewed by the outside world. Aren't we losing ourselves in this war? How do you look at this loss of individuality?

Roy: I think there’s a difference between literature and journalling. The latter is now often used as, to use your words, ‘a therapeutic exercise’. Literature is not a by-product of such an exercise, neither is it ‘catharsis’ as that word is used inappropriately these days. Catharsis is the result of watching a play or reading a poem: it is the effect, not the cause. The rasas too are effect of the aesthetic experience: we cannot experience what the writer has experienced, we can only experience the effect of the writer’s words through their peculiar form. We forget this difference all too easily these days.

Anything we can’t understand, we characterize as some form of ailment. Poetry feels like a foreign language to many, music is noise, cinema an indulgence. Everything is an ailment in that sense, including love—the reason we use an expression like ‘lovesick’.

The Chakkar: You have mentioned in the past that you find creative podcasts such as discussions amongst creative minds like filmmakers and artists more enriching than academia and discourses. Does a literary symposium make art too serious and nature-specific, while creative discussions are more free-flowing and liberating in nature?

Roy: I like flow—in life, in art, in conversations. As long as someone is not trying to plug their work or is using the discussion to promote their new film or book, I have noticed that most conversations can be interesting. It is true; I have learnt more about creativity and art from watching actors, directors, DoPs in conversation with each other, than I have from listening to writers. Actors on Actors, The Hollywood Reporter… some of the discussions in these places make me pause, take notes, compare what they are saying about their medium with literature; in India, I like to listen to Pankaj Tripathi: he will inevitably say something that will stay with me.

The Chakkar: I believe that music is a form of storytelling too, where each sound, bol, taal, laya, harmony, gharana, and symphony, needs to be well-thought of, written down, broken down into swaralipis and notations. Similarly, how important do you feel is the role of simple and complex words shaping or reshaping a story?

Roy: All words are simple and all words are complex. They have their histories, and I do not mean etymology alone: a history of users who have walked through the language, polishing it, neglecting it, using it, abusing it. Every single word we use is a commitment on our part to that history and to this moment of our aligning our history with that tradition. I test each word for how my body, particularly how my mouth, responds to it. It is my first index of the honesty of experience.

The Chakkar: Do you feel anecdotes and ‘research’ supplements add up to a story’s narrative, or is it the power of simplifying complex things in storytelling that builds its quality?

Roy: Everything is research—most of all, our lives. To think of research as belonging only to an archive is debilitating to creativity. By this I do not mean the narrow sense of our archive or those that come into our range of vision. Much research will always lie outside intentionality, and part of our work as people, whether we are artists or not, is to be receptive to these signals and our archives.

The Chakkar: As a reader, I think of you as a writer of this generation who cared for fellow humans, plant life, and her surroundings through her writings—long before the pandemic taught us to become more compassionate. How would you want yourself to be remembered?

Roy: Thank you, Ronald. I have neither the desire to be remembered nor the delusion that I might be remembered. Do we remember the grass that lived and died in the pathway?

The Chakkar: Please share one thing about Sumana Roy, the human, that many readers may not know about.

Roy: That I’m not an interesting person and there’s nothing about me that the ‘reader’ might find interesting. I don’t feel the burden to be an interesting person in a group. The things I like to do are mostly private, and their joys cannot be shared: the joy of playing with numbers in my head, for instance. Any information about the writer as a person is, for me, unnecessary.

***

Ronald Tuhin D'Rozario studied at the St. Xavier's College, Kolkata. His articles, book reviews, essays, poems and short stories have been published in many national and international online journals and in print, including Cafe Dissensus Everyday, Narrow Road Literary Journal, Kitaab, The Pangolin Review, The Alipore Post, Alien Buddha Press and 'Zine, Grey Sparrow Press, and more. He writes from Kolkata, India. You can find him on Instagram: @ronaldtuhindrozario and Twitter: @RTDRozario.