‘It’s Fair to Suggest that We Live in Two Indias’ – An Interview with Shashi Tharoor

MP and author Shashi Tharoor speaks about the legacy of B.R. Ambedkar, the British Rule, and puts forth an argument for a presidential system of governance in India.

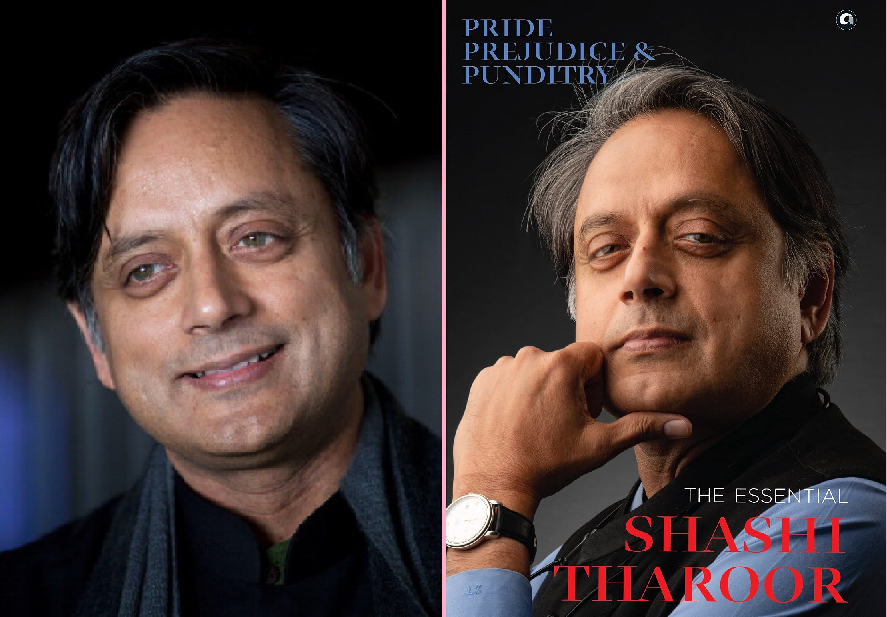

Shashi Tharoor’s recent book Pride, Prejudice, and Punditry (Aleph) brings together the very best fiction, non-fiction, and poetry from his published books and journalism. The subject of his next work will be B.R. Ambedkar in the biography Ambedkar: A Life, set to be published this year by Aleph.

The Congress Member of Parliament and author talks about Ambedkar’s legacy, the British rule, and puts forth an argument for a presidential system of governance for India. Here are edited excerpts from the interview.

The Chakkar: What are your views on Ambedkar’s legacy? Are we truly worthy of it?

Tharoor: As a political leader, Dr. Ambedkar was better at articulating powerful ideas than in creating the structures to see them through. None of the three parties he founded ever acquired the following or the permanence that his ideas deserved. But the Constitution of which he was the principal author remains the best instrument for pursuing his ideas. The leader and spokesman of a community left his greatest gift to all communities—a legacy that belongs to all of us, and one of which we are yet to prove ourselves wholly worthy.

“The kind of applause that a vitriolic post from Kangana Ranaut received compared to the intensity of the backlash that Vir Das’ monologue received… speak for themselves. Indians are clearly divided in their political opinions on almost every issue.”

The Chakkar: You have written extensive critiques of the British rule in the past. But were there any positive legacies to the Raj?

Tharoor: Many modern apologists for British colonial rule in India no longer contest the basic facts of imperial exploitation and plunder, rapacity and loot, which are too deeply documented to be challengeable. Instead, they offer a counter-argument: Granted, the British took what they could for 200 years, but didn’t they also leave behind a great deal of lasting benefits? In particular, political unity and democracy, the rule of law, railways, English education, even tea and cricket?

All these (except the first, since the idea of India is as old as the Vedas), may have been by-products of British rule, but none were created to benefit Indians. Institutions created to perpetuate British rule, entrench British dominance and enhance British profit cannot become legacies we should be thankful for.

Take the argument of the instrumental role played by the British in developing political unity. The fact is that throughout the history of the subcontinent, there has existed an impulsion for unity. The idea of India is as old as the earliest Hindu scriptures, which describe “Bharatvarsha” as the land between the Himalayas and the seas. If this “sacred geography” is essentially a Hindu idea, Maulana Azad has written of how Indian Muslims, whether Pathans from the north-west or Tamils from the south, were all seen by Arabs as “Hindi”, hailing from a recognisable civilisational space. Numerous Indian rulers had sought to unite the territory, with the Mauryas (three centuries before Christ) and the Mughals coming the closest by ruling almost 90 percent of the subcontinent. Had the British not completed the job, there is little doubt that some Indian ruler, emulating his forerunners, would have done so. In fact, far from crediting Britain for India’s unity and enduring parliamentary democracy, the facts point clearly to policies that undermined it—the dismantling of existing political institutions, the fomenting of communal division through a policy of “divide and rule” and systematic political discrimination with a view to maintaining British domination.

Similarly, as I have argued in great detail in An Era of Darkness, these other ‘gifts’ that apologists return to whitewash the misdeeds of the colonial enterprise were also passed on with the explicit hope of securing British dominance—the English language was not a deliberate gift to India, but again an instrument of colonialism, imparted to Indians only to facilitate British rule. The language was taught to a few to serve as intermediaries between the rulers and the ruled. The British had no desire to educate the Indian masses, nor were they willing to budget for such an expense. The Railways were constructed and expanded to serve British extractive interests and military dominance. And so on: all of these supposed benefits were designed and executed to perpetuate British rule, to fulfil British interests or to increase British profits. And often, all three. Indians were never the intended beneficiaries.

The Chakkar: Independent India is as divided as ever. You were one of the few politicians to call out the actor Kangana Ranaut about her comments, and also to stand by Vir Das after his viral ‘Two Indias’ video. Do you believe we live in two Indias now?

Tharoor: I think the kind of applause that a vitriolic post from Kangana Ranaut received compared to the intensity of the backlash that Vir Das’ monologue received—or that of the more severe strictures faced by another standup comic, Munawar Faruqui, who was jailed for a joke he didn’t even crack—speak for themselves. Indians are clearly divided in their political opinions on almost every issue, and to that extent, it’s fair to suggest that we live in two Indias.

The Chakkar: Regarding the fractures in our democracy, you have written about how the rich dividends of the presidential system of governance. Could you elaborate on the same?

Tharoor: Our parliamentary system has created a unique breed of legislators, largely unqualified to legislate. It has produced governments dependent on a fickle legislative majority, or majorities that serve as rubber-stamps for the government. I believe we need elected chief executives at all levels of government, independent of their legislatures, which in turn should be free of executive control to hold the government accountable. For example, village panchayats today are little more than glorified committee chairmen, with little power and minimal resources. To give effect to meaningful local self-government, we need directly elected local officials, each with real authority and financial resources to deliver results in their own areas. The Indian voter will be able to vote directly for the individual he or she wants to be ruled by, and the president will truly be able to claim to speak for a majority of Indians rather than a majority of MPs.

The Chakkar: Not many would agree with it though…

Tharoor: The only serious objection advanced by liberal democrats is that the presidential system carries with it the risk of dictatorship. But surely even they would concede that a President Modi could scarcely be more autocratic than any prime minister we have seen in office—one who has, thanks to the parliamentary system, a rubber-stamp majority in the Lok Sabha rather than the independent legislature a presidential system would ensure.

The Chakkar: What is next for you?

Tharoor: For now, I am taking some time off to spend it with my grandchildren in the US, two of whom I haven’t had the chance to see till now since they were born during the pandemic. Then back to India, it is, where I’m spending most of January in my constituency before returning to Delhi for what I hope will be a productive Budget Session of our Parliament.

***

Medha Dutta Yadav is a Delhi-based journalist and literary critic. She writes on art and culture. You can find her on Twitter: @primidutt on Instagram: @primidutt.