Love, Law, and Literature: A conversation with Danish Sheikh

‘I celebrate the ways in which queer people in the country have found ways of living with a law that hasn’t been particularly kind to their existence.’ Chintan Girish Modi interviews playwright/activist Danish Sheikh on his writing and the intersection of law, theatre, and queer sexuality.

On September 6, 2018, a landmark Supreme Court verdict read down Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code. This is an important date for queer Indians who have been haunted by the colonial law that criminalised lovemaking between adults in the name of forbidding “carnal intercourse against the order of nature”.

Three years after this momentous verdict, playwright, activist, lawyer, and legal researcher Danish Sheikh is ready to release his new book, Love and Reparation (2021 – Seagull Books), a text that offers “a theatrical response to the Section 377 Litigation in India”. Love and Reparation brings together his plays, Contempt and Pride, in a single volume, plays that were written in response to two judgements: Suresh Kumar Koushal vs Naz Foundation (2013) and Navtej Singh Johar vs Union of India (2018).

Sheikh is currently writing his Ph.D. thesis at Melbourne Law School in Australia, one that addresses the intersections of law, literature and performance. Prior to this, he was an Assistant Professor and Associate Director of the Centre for Health, Law Ethics and Technology at the Jindal Global Law School in India. He also runs Bardolators, a theatre group performing contemporary versions of Shakespeare in public spaces.

Love and Reparation is born of his profound engagements and entanglements with love, law and literature. In its pages, you will encounter his lovers alongside poet Mary Oliver, art critic John Berger, neurosurgeon Paul Kalanithi, psychoanalyst Melanie Klein, playwright William Shakespeare, cultural historian Maria Tumarkin, novelist Jeanette Winterson, and queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick.

Through the preface and the “bibliograph-ish notes”, Sheikh also tells the stories that unfolded behind the scenes and nourished the work that he made and presented. He draws on memoirs, anthologies, civil society reports, and transcripts of court hearings. He dedicates this book to “lawyers and activists who have fought tirelessly across decades, who continue to fight battles that only seem to get more difficult.”

“To speak of inadequacy doesn’t mean that equal rights as an LGBTIQA+ person aren’t crucial and desirable; it means that the conferral of those rights doesn’t by itself erase the shame and trauma of living life as an unapprehended felon.”

To mark the anniversary of this landmark September 6 verdict, we present an exclusive interview with Sheikh where he addresses his writing, apology and reparations, and the intersection of law, theatre, and queer sexuality.

The Chakkar: I get the impression that both Contempt and Pride were written to be performed. As the person who brought them into being, how do you feel about them existing as words on the page minus actors?

Sheikh: When I first set out to work on them, neither play was written to be performed in the sense of being developed for a production. At the time of writing Contempt in particular, I didn’t even think of myself as a playwright. I wanted to express something about the law that the genre of an academic essay wasn’t able to do; for instance, the specific effect of watching a set of courtroom proceedings, or the specific way in which we might present an affidavit differently. The theatrical form clicked for me as the best way to tell this story; but, in that initial iteration, it was written to be read, which also means that it was fairly easy to recraft into a book.

The Chakkar: Have you considered the possibility of turning it into an audio book?

Sheikh: I love that idea. I think it could work really well. I’ve had the chance to do Zoom versions of the play with actors in different locations and it seems to translate quite easily to a digital medium. It probably helps that the staging is fairly simple, so the potential listener doesn’t have to make the kind of imaginative leaps that a more dynamic piece of staging might require.

The Chakkar: How do you look back at all the research that went into writing both these plays? Could you take us through when and how it all began, and what made you jump into this work?

Sheikh: I was researching for the plays even when I didn’t realise I was researching for them. This goes back to my point about struggling with genre. I’ve done a fair amount of academic writing on both the decisions that these plays reference. This has included parsing through the courtroom hearings that would ultimately be featured in Contempt. It has also included following the kinds of conversations that played out in the wake of decriminalisation that are featured in Pride. The genres that I’ve written in include the law review article, the NGO report, the fact-finding report, and the newspaper op-ed. All of these allowed me to present a point of view, to advance a narrative, but stopped short of evoking something else that I was trying to get at: that sense of carrying the law in your body, of living and loving in dissent. I had a strong grasp of the material by the time I started writing both plays. It was more a matter of what to do with the material, how to rip it up, and stitch it together in a different manner from what I had attempted in the past.

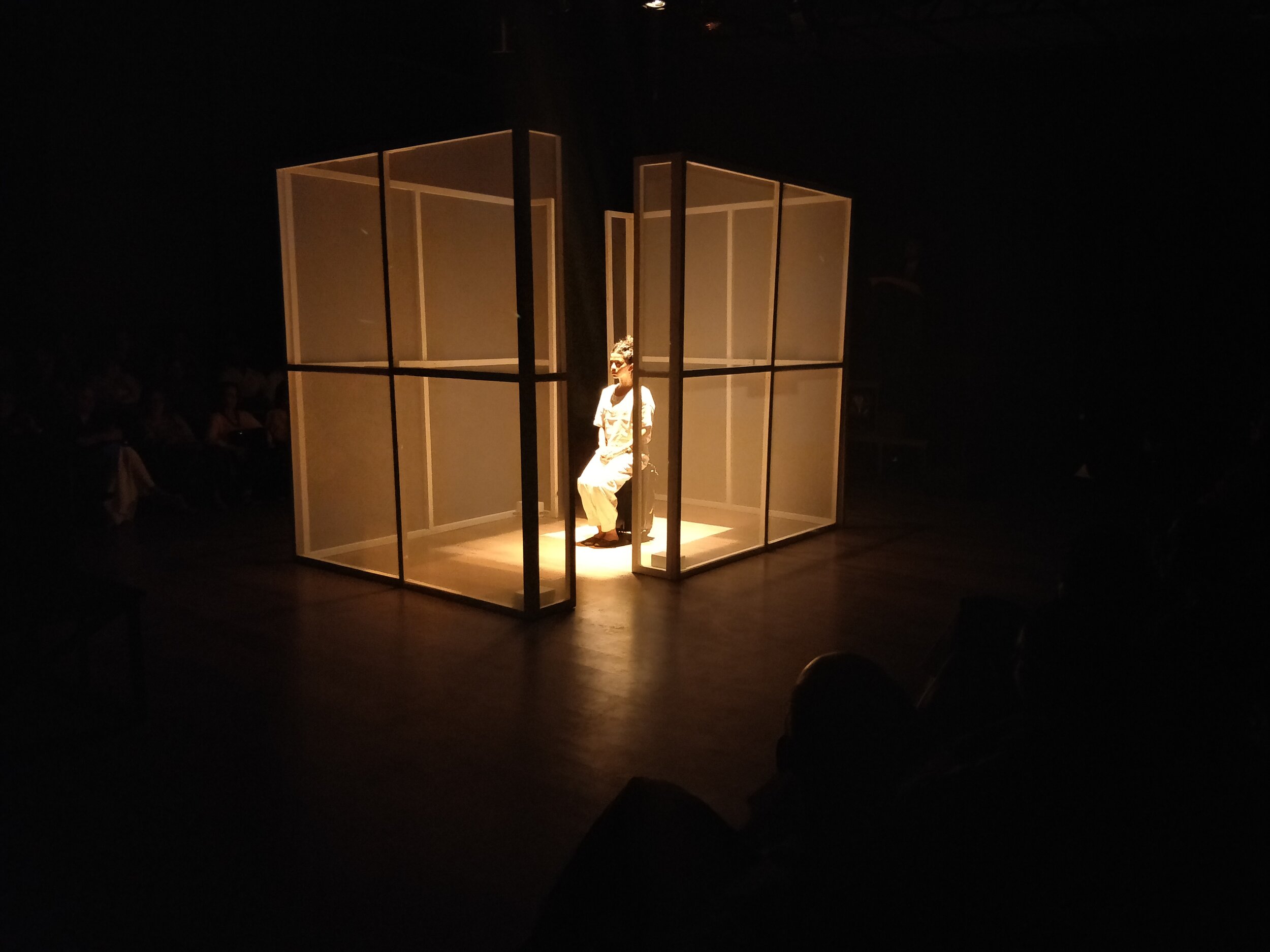

Performance of Contempt at Oddbird Theatre, Delhi - May 2018. Photo courtesy: Prateeq Kumar

The Chakkar: How do you feel about launching this book around the third anniversary of the Supreme Court ruling that read down Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code?

Sheikh: It feels quite fitting in some ways. My work isn’t a celebration of the decision itself. If I celebrate something, it’s the ways in which queer people in the country have found ways of living with a law that hasn’t been particularly kind to their existence. If I am not actively celebrating the Navtej Johar decision in the play, I am still very much in conversation with it and, to that extent, I do appreciate the proximity of the book’s release to the court ruling.

The Chakkar: Justice Indu Malhotra from the Supreme Court famously said, “History owes an apology to the members of this community and their families, for the delay in providing redressal for the ignominy and ostracism that they have suffered through the centuries.” How do you view the relationship between apology and reparation, at the level of both idea and practice?

Sheikh: I am thinking of Rahul Rao’s wonderful recent book Out of Time where a version of this question plays out in the context of the British Parliament and the relative ease it displays in offering an apology to the victims of colonial anti-sodomy laws, as opposed to those who were enslaved by British colonial capital. The apology is more easily offered in the prior instance because it doesn’t necessarily come attached with some form of material reparation. In the case of Justice Malhotra, it’s interesting because the apology comes as an addition to the “reparation” that the court is offering the queer community by way of the constitutional rights recognised by their decision. At the same time, the wording is curious, isn’t it? “History” owes an apology, not necessarily the state or even this very court, which only five years prior to this decision delivered a devastating verdict against the queer community. So, who is apologising here, and for whom?

The Chakkar: To what extent do you see your book contributing to the legal conversation around “sexual citizenship”, a concept that you introduce in the preface to Love and Reparation? Would you mind elaborating for people who may be new to this specific framework or articulation?

“What does it mean to celebrate a right to love that isn’t properly political, a love that calcifies, a love that is circumscribed by caste and class? What, for that matter, have we lost with this kind of narrow victory?”

Sheikh: Sexual citizenship is one way in which we might think about the formal conferral of rights upon queer persons following this major constitutional moment. I bring in the concept in large part to note its inadequacy, at least if we want to think about what it means to “be free” of sodomy law. To speak of inadequacy doesn’t mean that equal rights as an LGBTIQA+ person aren’t crucial and desirable; it means that the conferral of those rights doesn’t by itself erase the shame and trauma of living life as an unapprehended felon.

The Chakkar: In the foreword to your book, Tarun Khaitan writes, “What joy can India’s sexual minorities experience in a new-found capacity to love at a time when religious minorities are in the process of being deprived of that very right?” Let us assume, for a moment, that this isn’t a rhetorical question. How would you respond to it?

Sheikh: I suppose that one of the characters in the second play in this book represents a very real answer to that question. I am thinking about the man who can only understand the Navtej Johar decision as a springboard to a specific monogamous-married reality. This is not to delegitimise the right to marriage, or to take away from the need/desire that so many queer people have about entering the institution. There is however something in the way this character talks and positions themselves that should make us wary. What does it mean to celebrate a right to love that isn’t properly political, a love that calcifies, a love that is circumscribed by caste and class? What, for that matter, have we lost with this kind of narrow victory?

The Chakkar: I find that the framing of queer as the opposite of straight often keeps the focus on those who identify as gay, lesbian and bisexual but tends to exclude those who identify as asexual. Some even say that the A in LGBTIQA+ refers to allies. What are your thoughts on this?

Sheikh: I like that point: for one, yes, that binary oppositional framing can often defuse the potential of queerness in general and its use as an umbrella term for non-normative sexuality in particular. Even as an umbrella term, because of that association of sexuality with touch, we do risk invisibilising asexuality. I’ve been guilty of this in recent academic writing on queer touch where it had to take an academic who identified as asexual to point this out to me. This form of invisibilising is exacerbated by how undernourished our cultural imagination of asexuality is: it took me at least two minutes of wracking my brain before I was able to think of an asexual character in a work of popular culture, and even then, the example was an animated character (Todd in BoJack Horseman—great character, great show, but still).

The Chakkar: Let’s get back to talking about your own work. Love and Reparation is part of Seagull Books’ Pride List edited by Sandip Roy and Bishan Samaddar. Why did you choose to publish with them?

Sheikh: The question of fit is such a difficult one, but for me it was made easy in part by Seagull’s experience in publishing theatrical work. It also helped that I absolutely love Sandip Roy’s novel Don’t Let Him Know—one of the best things that I read in 2015 when it was released. When Sandip approached me about publishing my work with Seagull’s Pride List in 2018, it was a fairly easy decision. There is a great level of care and attention to detail that Seagull places in their work, which I have certainly experienced in my interactions with Bishan.

The Chakkar: Having crafted this “theatrical response to the Section 377 litigation in India,” what are your thoughts on the court hearings and affidavits connected to the various petitions to legalise same-sex marriage in India? Are you writing a play based on them?

Sheikh: It's interesting how pluralised the legal challenge has become now, with different strategies playing out across different courts. I think it speaks to the way in which the queer rights movement in the country—to the extent that you can call it a movement—has grown. It also means that a narrative thread, the kind that I might want to draw upon for a theatrical work, is harder to find. The other consideration for me is that I write from experience: the courtroom sequences in Love and Reparation benefit, I think, from the fact that I was physically present in the room when the respective hearings took place, while also being privy to many of the conversations that took place across different litigation teams. As far as marriage equality is concerned, I do care about the outcome but I don't have a ‘take’ on the question yet, of the kind that might inspire a new play on this question. But I am following the different petitions with interest and, if I think I have some commentary to offer, there's a fair chance that it will be in the theatrical register.

The Chakkar: I look forward to that. Before we conclude, what advice would you offer to students who, like you, are in love with law and literature, and hope to have a career that engages both these areas of knowledge and enquiry?

Sheikh: As a law student and then a lawyer, I’ve always started with a question of law. The law question has changed: at times it was a question of how the law impacted a community; at other times, it was a question of how a community reworked the law. Literature, and then theatre, became ways for me to approach those law questions. It could have been some other discipline, some other medium; it could have been psychology or history or visual art or geography. But I found myself specifically attuned to the literary and the theatrical. When I approach law within these registers, some kind of alchemical magic takes place, where I’m able to forge a certain sense out of something that didn’t make sense.

It all began with the law question, though! So, I suppose the ‘advice’ that I have is to think carefully about your responsibility as a lawyer in training, about the things you can do with the law, about the worlds you can make and break with it. Then think about these other mediums, other approaches, as tools to help you approach these questions.

***

Chintan Girish Modi has an M.Phil in English Language Education, and has worked with the UNESCO Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Education for Peace and Sustainable Development, the Kabir Project, and the Hri Institute for Southasian Research and Exchange. His writing has appeared in Bent Book: A Queerish Anthology, Fearless Love, Clear Hold Build, Borderlines Volume 1, and more. He can be reached at chintangirishmodi@protonmail.com and found on Twitter: @Chintan_Connect.