A Forgotten Rebellion: The Royal Navy’s Mutiny of 1946

Photo: Priyanka Chakrabarty

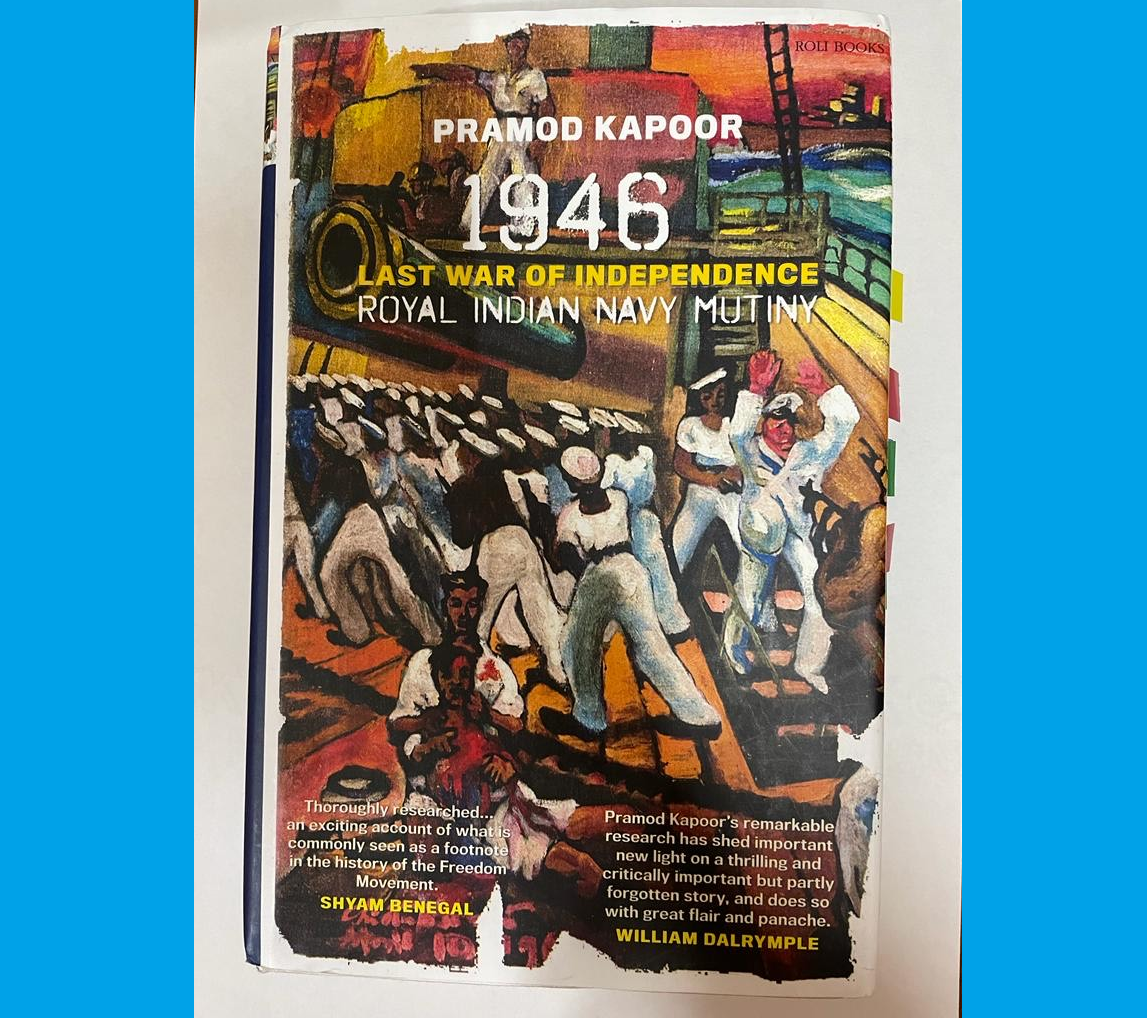

1946 Royal Indian Navy Mutiny: Last War of Independence adds yet another dimension to the existing accounts on the struggle for Independence. But how does our remembrance of history truly carry over to the present?

Often, public memories of historical accounts can reflect structures of power which relegate certain events as landmarks—while another kernel of the truth may remain just a footnote. In India’s struggle for freedom against British rule, the naval mutiny of 1946 is an example of one such footnoted event.

In his latest book 1946 Royal Indian Navy Mutiny: Last War of Independence (Roli Books, 2022), Pramod Kapoor traces the history of the Royal Indian Navy and the complex web of social, political, and economic factors which led to the uprising of the mutiny.

In 1946, colonial India stood at the brink of independence. During this time, the ratings—common soldiers of Royal Indian Navy (RIN)—staged a rebellion against the British to protest the inhuman conditions at work, unpalatable food, and rampant racial discrimination against them. Within a window of 48 hours, 20,000 ratings took over the British ships and presented a charter of demands. This mutiny was soon joined by civilians and servicemen across the Army and Air Force.

Eventually, this rebellion was suppressed by the British and the Indian leaders of the ongoing freedom movement. The incident would be largely erased from public memory, and in post-Independence India, leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru and Vallabhbhai Patel failed to acknowledge the contribution of the ratings to the nationalist movement.

Kapoor, in this book, attempts to make two arguments. He contends that Royal Navy’s mutiny was a decisive event that convinced the British that their colonial rule in India has come to an end. The book also argues that the mutiny deserved a larger share in the telling and retelling of India’s struggle for Independence, alongside key events such as Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919. The argument is further extrapolated to make the claim that, had the leaders of the nationalist movements—namely the members of Congress and Muslim League—taken the munity seriously instead of suppressing it, it could have made the event of Partition less bloody and more harmonious.

Of course, it becomes important to ascertain if the ambitious claim of the book is its vice or virtue.

Is it possible that the claim “I strongly believe that Partition would have been less bloody if the political leaders had tried to build upon the communal unity created by the events of February 1946, instead of ignoring it” suffers from historical fallacy? It is imperative that we take a few steps backwards and raise the crucial question: Why do we read historical accounts at all? These accounts are anything but chronological events that have taken place in the past. In fact, the past shifts, like a kaleidoscope, displaying a new pattern of events depending upon the present context through which the past is interrogated. The claims on the basis of such knowledge are called “historical fallacy” an idea that was first enumerated by British poet and critic Matthew Arnold in his seminal essay The Study of Poetry. This book and every other historical account have the advantage of knowledge of subsequent set of events that have since followed particular historical events, till the present date.

The argument is further extrapolated to make the claim that, had the leaders of the nationalist movements taken the munity seriously instead of suppressing it, it could have made the event of Partition less bloody and more harmonious.

The naval mutiny of 1946, in Kapoor’s book, has also been compared to the Sepoy Munity of 1857, which has been etched in public memory as the first major war of Independence waged against the British. It had the power of shaking the foundations of British rule in India. This was the first event that clearly sent a message to the English rulers, that their rule in this land shall not be unchallenged.

While the sepoy mutiny of 1857 and the naval mutiny of 1946 has its similarities, as both mutinies being waged by wings of the army under the control of the British, that’s also where the similarity ends. The contexts in which both the mutinies take place are strikingly different. The mutiny of 1857 is a landmark event, because in the 19th century, there was an absence of an organized pan-India movement for Independence. By 1946, when the naval mutiny took place, there already existed a social and politically-organized movement for Independence. The national Independence movement had gone through a number of crucial and decisive events, including the Quit India Movement of 1942—also known as August Kranti—posing a non-violent challenge to the British rule in India. The Mutiny of 1857 was a standalone event marking the beginning of a long struggle against the British Rule, while the naval munity of 1946 is one of the many events that occurred during a crucial time in Independence movement, when the possibility of political independence was already being negotiated with the British.

In the text, Kapoor succinctly captures the chronology of events of the fateful month of February 1946 and the events leading up to the mutiny. The book ends with grounding us in the present day, where the readers are given a glimpse into the lives of the leaders of the mutiny. Their current lives are elaborated upon, to drive the point that even in the 21st century, nearly 75 years after the independence, the political parties in power have not acknowledged the immensity of the event; neither have they fulfilled the promise of honouring the veterans with any form of state recognition. In the construction of historical narratives, individuals in power determine the names and lives that ultimately get the spotlight of being national heroes.

1946 Royal Indian Navy Mutiny: Last War of Independence adds yet another dimension to the existing accounts on the struggle for Independence. But how does our remembrance of history truly carry over to the present? In India’s political and social context 2022, when history is being re-written blurring lines of fact and fiction, where does this retelling fit in?

Retellings of historical accounts are riddled with ‘what ifs’, a question historians speculate upon endlessly. Kapoor’s claim that the leaders of Congress and Jinnah corroborated with the British to suppress the mutiny, because it played to their political interests, is perhaps is a comfortable position. It ignores the nuances of a time period where leaders were carrying out the crucial negotiation for Independence. While historical accounts bear the burden of glaring on forgotten events, perhaps they also bear the burden of analysing it with humility, one that doesn’t lapse into the easy binary of the saviour and the condemned.

***

Priyanka Chakarabarty is a neuroqueer person and law student based in Bangalore. She aspires to be a human rights lawyer. An avid reader of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry, she has been writing in the genre of creative non-fiction. She is a bookstgrammer and regularly documents her reading journey on Instagram: @exisitingquietly.